When Outlook magazine approached me with the idea of creating a jury to select India’s 50 best CEOs, my first thought was, “These guys are nuts. It can’t be done.” How do you wade through an ocean of names to truly pick the 50 best, especially if some of them may already be resting with the morning angels? But soon after I had fobbed off the Editor with a non-committal reply, some names started popping up into my head. Surely, a business like Infosys could not have been created without a great CEO or progenitor? Could HDFC Bank’s extraordinarily consistent results for a quarter century be the result of providence and not great leadership? How does an ISRO become one of the world’s most competitive and efficient satellite launchers (at the time of writing, its record of launching 104 satellites in one go still stands) despite being a government outfit? Surely, leadership had something to do with it?

When we look behind the great success stories, names start bubbling to the surface. And it no longer seemed an impossible task to isolate some of India’s highest-performing CEOs. The problem was always about restricting the number to 50, for India has never lacked achievers. The challenge thus seemed too important to duck and so we were on. On a bright Sunday morning in February, Omkar Goswami, veteran of many government committees and corporate boards, Sanjaya Baru, former media advisor to Manmohan Singh and a celebrated economist-journo, and I were neck-deep in prospective names that could make it to the final 50.

A few caveats are in order.

First, we do not claim that the final 50 CEOs you see on the accompanying list are the only ones deserving to be on it. Some more names could have been added. But these were the names we could agree on. When we could not agree on a name, we dropped it, even though it may well have been deserving. Conversely, it is possible to claim that some may not be as deserving, and we accept that is a limitation imposed by our subjective knowledge of all the CEOs we considered.

Second, we deliberately omitted many of today’s new sectors—for example, online retailing, where hundreds of crores are being invested and whose CEOs are celebrated as big achievers. This is not because the sector isn’t producing great CEOs, but because it is difficult to decide which ones will fall by the wayside as competition heats up and business models get up-ended. We played safe by not selecting ‘possibly good’ CEOs as the outcomes of their efforts are not clear. Good effort alone does not define a great CEO. We need them to be tested by time as well.

Third, we have probably not done justice to extraordinary performers in the mid-cap and smaller sectors and organisations, since there may simply be too many of them. For example, our list has the late Qimat Rai Gupta of Havells, who has built both a great business and a brand out of almost nothing, but I am sure there are other Guptas we have not taken note of. Apart from the impossibility of choosing a handful from an almost endless list of probables, it is best to see Gupta as representative of great leadership in some of the smaller businesses rather than fretting about why he was the only one chosen. Also, at some point success breeds size. Perhaps it was good to be conservative about excluding smaller successes in the expectation that success will make them big.

With these caveats out of the way, we can now explain how we went about whittling down the list to 50 from a sea of names.

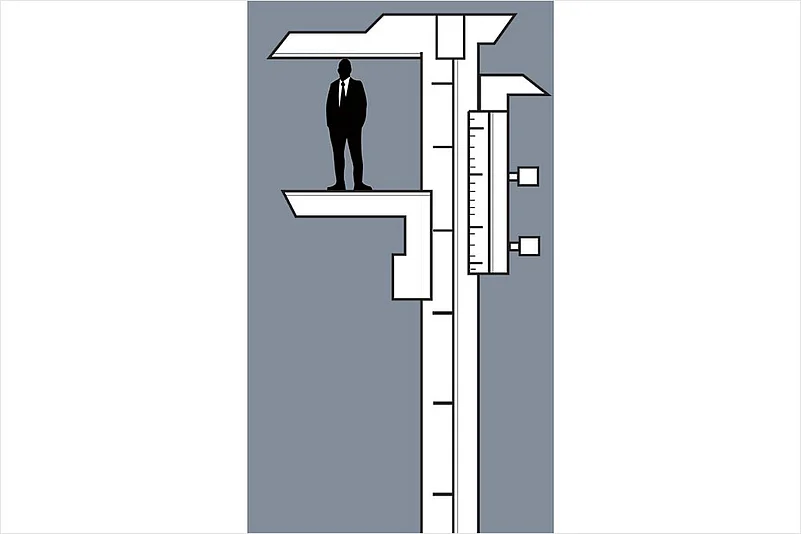

When the jury met, we started with an exhaustive list of CEOs who could make the cut. We toyed with the idea of scoring CEOs on numbers, like profitability performance, leadership, etc, but abandoned it when we saw that we would be comparing apples with not only oranges, but jackfruit and pineapple too. The organisations and CEOs who stood out worked for completely different kinds of organisations—some in government, where profit parameters don’t always apply, some as business group heads, where actual performance may depend more on CEOs reporting to the group boss, and some in industries where the measures of success were difficult to compare. How, for example, would you compare the performance of K.V. Kamath at ICICI Bank with, say, E. Sreedharan, who built Konkan Railway and the Delhi Metro?

We decided to compare leadership as a composite attribute rather than a sum of the parts. We also decided against ranking the CEOs from No 1 to No 50 for the same reason, though Outlook would have been happy if we did manage to do this. We considered it unfair to talk of one CEO as the best ever, and another as the 50th best, when both rankings would be questionable. Instead, we opted to categorise the 50 CEOs into three groups, with the top group being CEOs of extraordinary impact, the middle group a little less so, and the third group as great CEOs in their own right, but successful in a different way.

Another conceptual difficulty we overcame was the classic promoter-CEO versus professional CEO, and the founder versus inheritor comparison. In India, promoters are often CEOs of the companies they found, and their successors often are from the same family. It would have been easier to exclude promoter-CEOs and inheritors and focus the ranking on professional CEOs alone, but this would have been a travesty, for it would have excluded some of the best and brightest among India’s business leaders. If a Dhirubhai Ambani, the man who single-handedly created the equity cult and built a world-scale business in Reliance, is excluded, and so is his son Mukesh, who is blazing new trails in telecom in what could be called India’s largest start-up, how much poorer would our list be? Promoters and inheritors can be CEOs who created huge value, and thus we decided we won’t try to restrict it to so-called professional CEOs.

Choices in the public sector were difficult to make. Despite the general sloth associated with managers working within bureaucratic limitations, the public sector has the largest repository of great managers, a fact emphasised by the speed with which retiring CEOs are snapped up by private sector promoters. This is partly because the really big projects of the past were all in the public sector, whether it was the giant Kudremukh iron ore project, or large steel and power projects, or major space, defence or urban infrastructure projects. Public sector managers are more used to handling thousands of crores in investment, and anyone who can handle this can probably walk into any private sector job. But when we look for sustained performance in public sector jobs, we found that very few names can actually make the cut, especially since longevity of tenure is needed to link a successful company or project with one particular CEO. A successful company may have a procession of CEOs serving time, and we can hardly call them great CEOs just because they happened to be in the right project at the right time.

The other tricky aspect in Outlook’s 50 Best CEOs project related to the choice of CEOs who may be long dead and gone. How do we compare someone who may have left the scene two or three decades ago with someone who is still running the show right now, and in completely different sets of circumstances? How do you compare the performance of a late CEO who operated during the licence-permit raj with one today who may be negotiating the regulator raj, and facing intense domestic and foreign competition? We didn’t actually try to do this, but have let the durability of achievement to speak for itself. The unsaid logic is that if someone succeeded in the 1970s and the monument to his success still endures, he surely did something right, if not great.

It may not be possible for us to compare Don Bradman with Sachin Tendulkar, two great batsmen who played in different eras, facing different kinds of bowling attacks and on differing pitch and weather conditions. But it is possible to put both of them in the same Hall of Fame because we know that true greatness will shine through whatever the superficial differences in the conditions in which they achieved greatness.

With this, we humbly commend our list of India’s 50 Best CEOs.

(The author is a senior journalist, and editorial director of Swarajya magazine and website)