But, apart from Brahmins, the past two decades have proved that the educated middle class can adapt to business like fish to water, it can make money instead of merely balancing accounting ledgers, it can lead and manage employees from the front rather than merely nudge the nation's destiny from the shadows, and it can become competitive, cutthroat and innovative, apart from just following the rules. The Brahmin and educated middle classes have now become the new cradles of entrepreneurship.

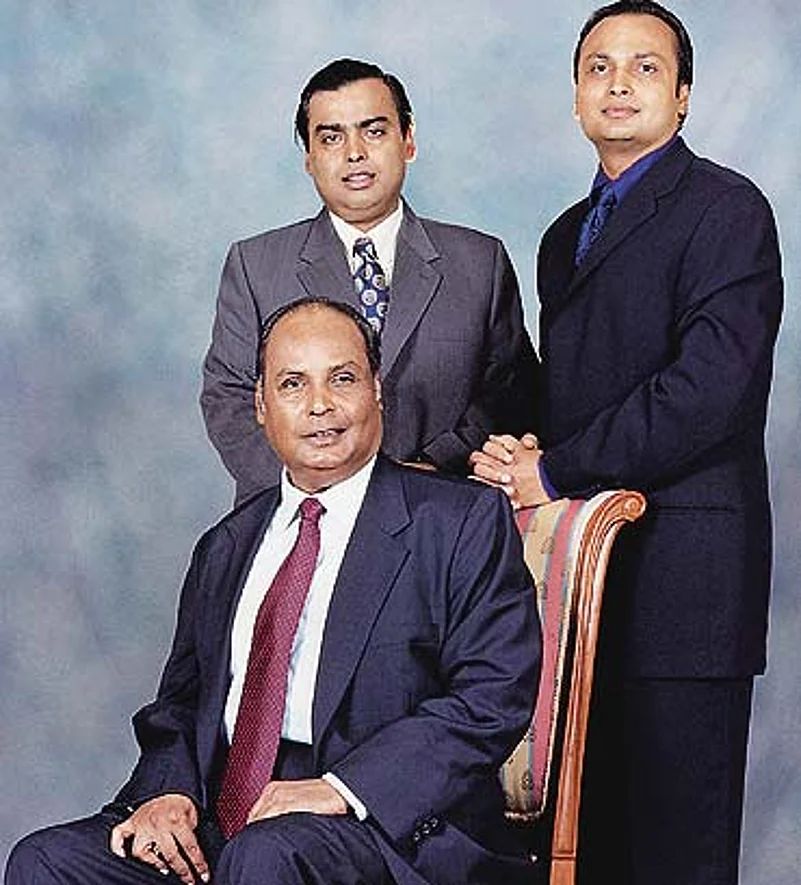

Obviously, like most traditional business groups, these new ones claim nondescript beginnings. The old scions have their own legends—Shiv Narayan Birla began trading in cotton in the 1850s, Nusserwanji Tata was the first member to break out of the traditional priestly profession, H.P. Nanda of Escorts came to India during the Partition days with Rs 5,000 in his pocket and Dhirubhai Ambani was the son of a schoolteacher. Of course, the Bajajs and the Mafatlals have their own "humble" and "modest" beginnings.

Several neo-businessmen too claim they came from middle- or lower middle-class families. Ramesh Vangal runs a global conglomerate, but his father was a Class II government officer for most of his tenure. Arjun Malhotra, head of IT consulting firm Headstrong, was born in an army family; his father took part in the '62 war. Polaris promoter Arun Jain's father was in the post and telegraph department.

More interestingly, Rana Kapoor, founder of Yes Bank, says his 'educated' father refused to run the family's jewellery business and decided to take up a job instead. "My grandfather sold three stores just before the Gold Control Act, after which others made massive profits, as none of his sons wanted to inherit the business," says Kapoor. However, as a child, while playing chess with his grandfather, Kapoor would regularly comment, "Don't worry, one day I'll become a businessman."

Among the many differences between the old guard and the young turks was education. Unlike many of the former, almost all Brahmin businessmen went to premier institutes like the IITs and IIMs. Their parents believed in, and forced them to take advantage of, independent India's fascination with, and passion for, higher education. "Nehru made a lot of mistakes but he got some things right. It was because of his attitude that the IITs were saved, and have now become the biggest brand from India," says Malhotra.

Thanks to such academic background, the Vangals and Kapoors became seasoned, global professionals, their career profile more entrepreneurial than merely managerial. More importantly, it convinced them that the older businessmen were missing out on new opportunities in the sunrise sectors emerging in the more open, 'reformed' Indian economy. Finally, it gave them the confidence that they could change things and inculcated in them an abiding belief in the India story.

Vangal, for instance, joined Pepsi in the '80s to kickstart its controversial and contentious India project. The stint taught him both about dealing with government and operational practicalities. "It was a traumatic period, both personally and businesswise. We were the guinea pigs who got hammered around by all the interested parties. But it was a fantastic, lasting learning experience." Kapoor worked with Bank of America andANZ Grindlays and got a sense of global banking benchmarks.

As global souls, they spotted new opportunities and learnt to think in terms of global strategies. Malhotra and his colleagues were aghast when DCM Data Products decided against making computers. "We thought it was crazy. We understood the global paradigm shift that was happening in technology. We knew the market, contacts and design," he reminisces. This led to the birth of HCL which, initially, traded in calculators as it was more profitable.

With his partners, Jain started programming for BILT out of a lack-of-cash compulsion. "It was the only way to enter business. But manufacturing remained an attraction. In 1983-85, we would discuss plans to make watches, electronic gadgets, chips or other semiconductor components," he explains. The mindset changed when Jain spent two months at Wang Labs in the US. "I saw a thousand people working on software and realised the global needs. There and then I took the decision to remain in software."

But they were all thinking big and wanted to compete globally as that was what they had seen and imbibed. So, Kapoor wanted his bank to be world-class and compete with international brands. Explains Vangal, "I want to carve and create a large vision, scale up the various businesses to a certain level, invite financial or technology partners to enable these to become truly global and competitive."

For traditional businessmen, the globalisation urge dawned late. In the licence-quota raj, they thought in terms of the protected domestic market, grabbing licences to deter newer players, and competing with inefficient PSUs. They worked the system, policymakers and other lobbies to influence decisions in their favour. Even in the immediate post-reforms era, the Bombay Club clamoured for slower reforms and a level playing field against the foreign onslaught.

Although there were a few visionaries, most groups became global only when it came to choosing between survival and death. The '90s witnessed the decline of business families like the Modis and Dalmias. The ones who managed to thrive were those who became globally competitive. It was because of those efforts that we are now witnessing the making of the Indian MNCs, like Tata Steel, Hindalco, Ranbaxy Labs and Reliance Industries, who are gobbling up huge global firms or setting up the world's largest factories.

The critical change in India's 60-year corporate journey is the manner in which the Brahmins and the middle-class entrepreneurs became risk-takers like their traditional counterparts. One of the triggers was personal confidence. "In 1985, when I went to Harvard," says Malhotra, "I realised I was not inferior to the whites. I was good at managing huge numbers of people. The whites knew how to deal with finances. But I realised that their skill was easier to learn; and I could do it from books. Mine was more experiential and, therefore, could not be learnt easily."

Kapoor had his own reasons to feel that India could become America. "During my MBA, I saw the beginnings of the success of Indian-Americans, who bought houses and cars. I was convinced that if Indians can make it in America, they can in India too." Fortunately, Vangal, Jain and Kapoor did not need the initial investments; they could raise funds in innovative ways in the changing global economy.

The second trigger for the increase in risk appetite is the conviction that India's is the next economic story, after China. "I believe India's arbitrage potential is enormous. There is something inherently strong in our economy," feels Vangal. Adds Kapoor, "India is at the centrestage of the global economy. And its future will be driven by entrepreneurship." The final word comes from Jain, who thinks there is huge social change happening right now in India. "The current generation doesn't have the responsibilities their parents did. It increases their risk-taking abilities."

Welcome to the gilded age where Brahmins have become businessmen, mantra-mutterers have become materialists, and strategy, not salvation, has become their new sloka.