Euphoria. That’s what the Modi government was hoping for earlier this month when it announced an “unprecedented hike” in the minimum support price (MSP) of 14 crops. But it seems to have proved a damp squib, with farmers’ groups planning a two-day meeting to chart out their protest plans. The new MSPs announced on July 4 are based on a formula to calculate the cost of production that differs from the formula favoured by farmers themselves, and the increase is being criticised as insufficient. The government is using the A2+FL formula, with A2 covering input costs such as expenditure on fertilisers, seeds, hired labour, fuel, irrigation etc., while FL is the imputed value of unpaid family labour. The alternative is the C2+50 per cent formula, where C2 also takes into account rent on land and interest on capital—the National Commission on Farmers headed by M.S. Swaminathan recommended this formula as over 20 per cent of cultivation in India occurs on rented land. But the government has been steadfast in telling Parliament and the Supreme Court that it did not favour the C2 formula.

Reacting to the government’s decision, Swaminathan points out in a statement that while the “MSP announced is higher in absolute terms,” it is “below the recommended level.” He argues that, contrary to the government’s claim of ensuring 50 per cent return on investment, the actual income of farmers is likely to be much lower in most cases. For example, the MSP of common paddy has been hiked from Rs 1,550 to Rs 1,750 per quintal. Taking the C2 cost of paddy last year (2017–18) and assuming a 3.6 per cent rise in input costs based on the input cost index used by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP), the estimated C2 cost for this year (2018–19) is Rs 1,524. So, the new MSP is C2+15 per cent, not C2+50 per cent. In the case of ragi, the new MSP is C2+20 per cent. Similarly, for moong, the MSP has been raised from Rs 5,575 to Rs 6,975, so it is now C2+19 per cent.

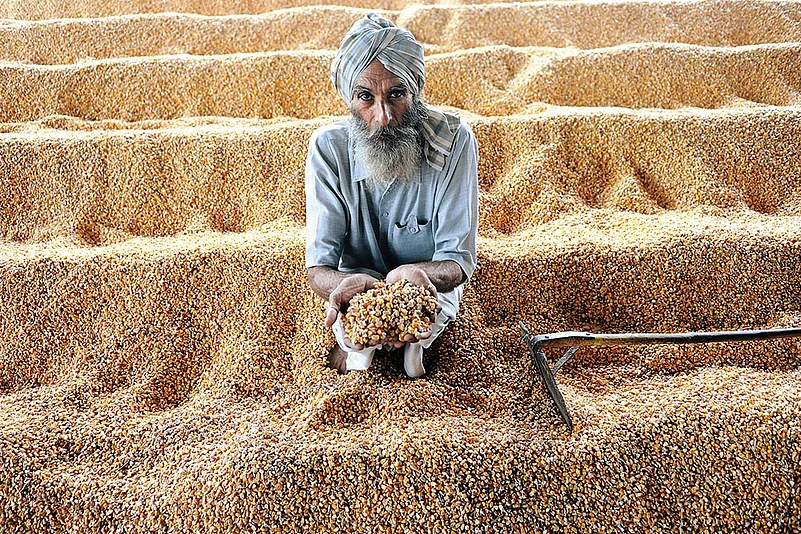

Sharing the farmers’ concerns, Swaminathan says, “Higher MSPs are welcome but there is inadequate public procurement at MSP, except wheat and rice. This is clear from the experience of farmers who cultivated more pulses on the expectation of procurement, but were let down by a crash in market prices. Indeed, for many crops including urad, tur, maize, groundnut, soyabean, bajra, rapeseed and mustard, the weighted average mandi price was below the corresponding MSP before the monsoon.”

Raju Shetti, MP and president of the Maharashtra farmers’ group Swabhimani Paksha, says the hike in MSP is commensurate with the rise in input costs, and thus incomes have not risen. “Not all farmers are happy as the hike will not ensure the promised return over input costs, which have risen post implementation of GST in products like PVC pipes, plastic for mulching, spray pumps, spare parts, chemical fertilisers, etc.,” says Shetti. This is borne out by the input costs estimates in the Maharashtra government’s cost of cultivation studies.

Farm activist Kiran Kumar Vissa underlines that given the importance of a good price for farmers, a better MSP has long been pending. This has made agriculture a loss-making proposition in innumerable cases, leading to hundreds of suicides annually. Yet, the new MSPs are generally too low. “Even after this much-hyped increase, it is not at the level the farmers require because the government is underestimating the cost, which is why the prices are very low. Even the MSP announced recently for many of the crops won’t give farmers sufficient profit margins,” says Vissa. He cites the example of paddy, which does not give sufficient returns despite the hike in MSP. “In the case of cotton, while the price has been raised sufficiently, it may not benefit the farmers as procurement has not happened properly in the past. So whatever the MSP announced, farmers are not going to realise the benefit,” claims Vissa.

V.M. Singh, convenor, All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee, the umbrella organisation of 194 farmer groups, states that except sugarcane, every single crop is sold below MSP except when government agencies step in to do procurement. “Every single grain must be bought by government agencies, or the government must ensure that farmers get at least the MSP. Currently, government procurement is hardly 5–6 per cent of the total production of wheat and rice, which means most farmers don’t benefit from government-fixed MSP,” says Singh.

Over the last few months, following the example of states like Madhya Pradesh and Telangana, the Centre has been studying different procurement models mooted by NITI Aayog—including the Price Deficiency Procurement Scheme, already under implementation in MP.

Agriculture activist and former UP Planning Commission member Sudhir Panwar argues that without a proper procurement policy, which currently favours only a few states— leaving out many less developed states like Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, etc.—the government should step up procurement and provide better budgetary support. Panwar points out that last year, several crops including paddy, mustard and tur among others were sold below MSP. “The government should announce the quantity of procurement state-wise and make budgetary allocation for it,” he says, adding that without adequate storage and budgetary support, procurement is counterproductive as it can lead to food being damaged.

S. Mahendra Dev, vice-chancellor of the Indira Gandhi Institute for Development Research and former chairman of CACP, says MSP caters mostly to rice and wheat. He fears the move to hike paddy prices by Rs 200 per quintal may push farmers to cultivate the most water-intensive crops, like sugarcane. “The present hike in MSP does not make much sense, as the government does not have a plan to ensure all farmers benefit,” Dev says, warning that the hike may increase market prices while public spending on procurement also rises, with Rs 15,000 crore—around 0.1 per cent of GDP— earmarked for the purpose. Together with higher costs of storage, some impact is likely, with inflation predicted to rise by 0.3 to 0.5 per cent.

The question is whether the way to improve farmers’ income is MSP or the market mechanism (reforms and removal of the middleman). The government has pledged to double their income through such reforms. The MSP hike comes at a time when the GDP deflator for agriculture (prices used to measure GDP for agriculture) is sliding. “The GDP deflator for agriculture was around 12 per cent in 2014–15, but declined to 7 per cent in 2015–16, and last year it was 1.1 per cent . There is deflation in agriculture as farm prices have come down due to demonetisation and other factors. So there is a need for farmers to get better prices,” says Dev.

Farmers across the country have grown more vocal over the last year or two. Given the BJP’s promise to double farm income, and a possible loan waiver as witnessed in several states, farmers are understandably unwilling to let go of the opportunity ahead of the 2019 elections. Can the government afford to overlook this segment of voters? On farmers rests not only the future of many politicians, but also the economic wellbeing of many corporates looking to a rural demand revival to mark a good profitable year.