Cure And Ailment

- The PM wants to bring law mandating doctors to prescribe only generic medicines

- Generic medicines generally cost a fraction of what branded medicines cost

- Chemists usually do not stock generic medicines as branded medicines give them hefty margins

- There are no generic medicines for 80 per cent of the branded medicines

***

Last week, the Prime Minister hit a hornet’s nest by suggesting that he will bring in a law that will mandate doctors and physicians to prescribe only generic medicines instead of brands. The proposal that has the potential to drastically change the pharmaceutical landscape in the country has alerted drug manufacturers, doctors and activists alike. For, if implemented, it can, in one stroke, make medicines cheaper for patients and bring in an ethical medicine regime in the country, while severely hitting margins of drug manufacturers and chemists.

Following the PM’s statement, the Medical Council of India (MCI) issued a statement on April 21, reminding doctors of MCI’s circulars of November 2012 and January 2013 as well as an amendment to the Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) regulations 2002 in September 2016, which directed doctors to prescribe generic medicines.

Generic drugs have the same composition as branded drugs and are made after the patents of the latter expire. They have the same pharmacological effects as their branded counterparts and are sold under their generic names. These generic names are internationally agreed short names called International Non-Proprietary Names. There are 30,000 companies in India manufacturing pure or branded generics.

The proposal aims at attacking and finishing off the ‘doctor-drug company-chemist’ nexus, which, on the one hand, is making medicines extremely expensive for patients and on the other, is helping chemists and pharma companies make huge margins.

Interestingly, the proposal to mandate doctors to prescribe generic medicines has existed in MCI guidelines but has never been implemented. Even the current notice from MCI is not mandatory. This was also taken up by the UPA government with the then PM Manmohan Singh pushing it. Yet nothing came of it.

Activists have been crusading for this for a long time and feel that the government should have a proper drug policy that forces companies to manufacture generics along with the law mandating generic prescription. “Most of the doctors are taught in generic names during their medicine courses and in medical journals. Only marketing is in brands,” says Dr Mira Shiva of the All India Drug Action Network (AIDAN).

It’s a given that there is a huge difference in price between generic and branded medicine as quality generics are available at a fraction of their branded price. While a generic medicine can be manufactured for 50 paise to Rs 1, the same drug in its branded form is sold at anything between Rs 10-30 in the market. For instance, the ultra-broad-spectrum antibiotic Meropenem injection, prices vary between Rs 950 and Rs 3,000 from the same company while some others sell it for as little as Rs 600. Unfortunately, only a few generic drugs are actually available in the market as they do not give big margins to chemists who make the maximum profit margin by stocking branded medicine and in a way forcing people to buy them.

Chinu Srinivasan, a generic drug manufacturer who also works with Locost, a Vadodara based organisation that works towards making essential medicines cheap and available to the poor believes the idea is a good one but only in theory. “In practice, it is not going to work in India as the necessary regulatory infrastructure is not there. The necessary mindset among doctors is also not there. It is giving the impression of creating access to cheap medicine without actually creating the infrastructure and system for it,” he says.

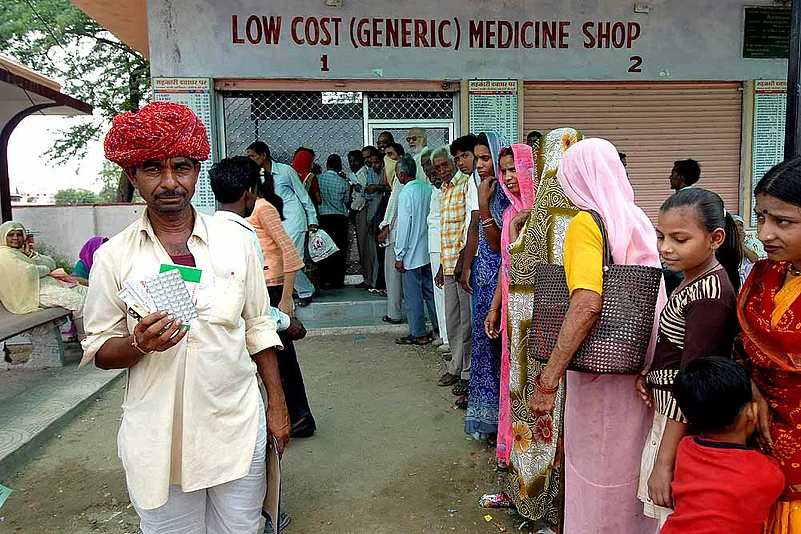

It’s true. The government in most states is yet to set up a proper system for distributing low cost medicines to the poor. “The benefits of generics do not reach the needy in India,” believes Leena Menghaney of Doctors Without Borders, India. “A majority of states in the country do not have an efficient procurement and distribution mechanism for medicines. This is present only in Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu and Kerala. People in other states are dependent on private chemists for all their medicines.”

There are practical problems as well. There is no generic equivalent available in the market for 80 per cent of the drugs in circulation. A majority of what is available is not in regular manufacture or is not stocked by a majority of the chemists in the country. The other issue is that of fixed dose combinations or FDCs such as Combiflam or Ibuprofen, which are prescribed by doctors for many common ailments. About 45-50 per cent of the market is made up of FDCs worth about Rs 45,000 crore. These medicines are a combination of many different drugs in fixed doses. If a doctor were to prescribe generic names for these then they would have to write a large number of generic names in their prescriptions. Also, those exact combinations might not be available in pure generics.

The total domestic pharmaceutical market is of about Rs 1 lakh crore. Of this, the generic medicines account for about Rs 10,000 crore. About four per cent of the market consists of medicines that have been put under price control by the government under the Drug Price Control Order 2013.

As expected associations like the Indian Drug Manufacturers’ Association (IDMA) and Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance (IPA) are worked up over the PM’s proposal and are trying their best to stop the law from being passed. “We share the Government’s concern to make medicines affordable for all,” says Deepnath Roy Chowdhury, President, IDMA and MD Strassenburg Pharmaceuticals. “However, certain developments seem to suggest that ‘generic’ is the solution. We would like to clarify that as per the DPCO the same ceiling price applies to all medicines whether generic or branded. Therefore though the intent may be good, converting to generics may not yield desired results. Furthermore, the right to choose the product will shift from the doctor to the chemist and the government must consider the pros and cons of this before taking a final decision.”

IDMA has suggested that if the government wants to give cheap drugs, it should allow doctors to prescribe both the brand and the generic composition so that the doctor can exercise his right to show his preference for a particular brand.

There is also the issue of quality of generic products made by smaller companies vis-a-vis branded generics or branded products from larger companies where a certain quality is assured—an argument doctors always bring forward.

Experts assert that the government should regulate chemists along with making generic drugs mandatory as they make the maximum margins. In many cases the margins are as large as 500-1000 per cent on medicines. “There is rampant profiteering by chemists,” says Menghaney. “Some of the most affordable drugs are not stocked by them. They stock only expensive branded generics and drugs.” Chemists have little or no incentive to stock or sell low-cost generic medicines as they have lower profit margins. Retail pharmacies have also no interest in selling low-priced branded medicines unless they are fast moving.

Then there is the strong nexus between doctors and pharma companies who are used to luring doctors to prescribe their brands in return for favours and incentives. In many cases these incentives extend to giving vacation tours in the name of conferences to paying even car and house EMIs. Against this, doctors become obliged to prescribe branded drugs or branded generics of some companies and skip out on the generics.

Many doctors, however, are supportive of the PM’s move and say that it will be easier for them to prescribe generics and that this can solve the problem of high drug costs in a large way. “We are much more comfortable prescribing generics but it should be available to the patient as most chemists will not stock or give it. There should be a policy that forces chemists to stock generics,” says Dr. Ajay Kumar Gupta, VP, East Delhi Physicians’ Association.

What may happen if the law becomes a reality is that doctors will write an official prescription with generic medicines and another one with their preferred brand names to satisfy chemists and companies.

Obviously, it will take more than a simple law to mandate generic prescription to solve the problem. The government will have to rein in the chemists and rationalise the margins they make from some branded and generic medicines if it wants to truly ensure low-cost drugs for Indian citizens.