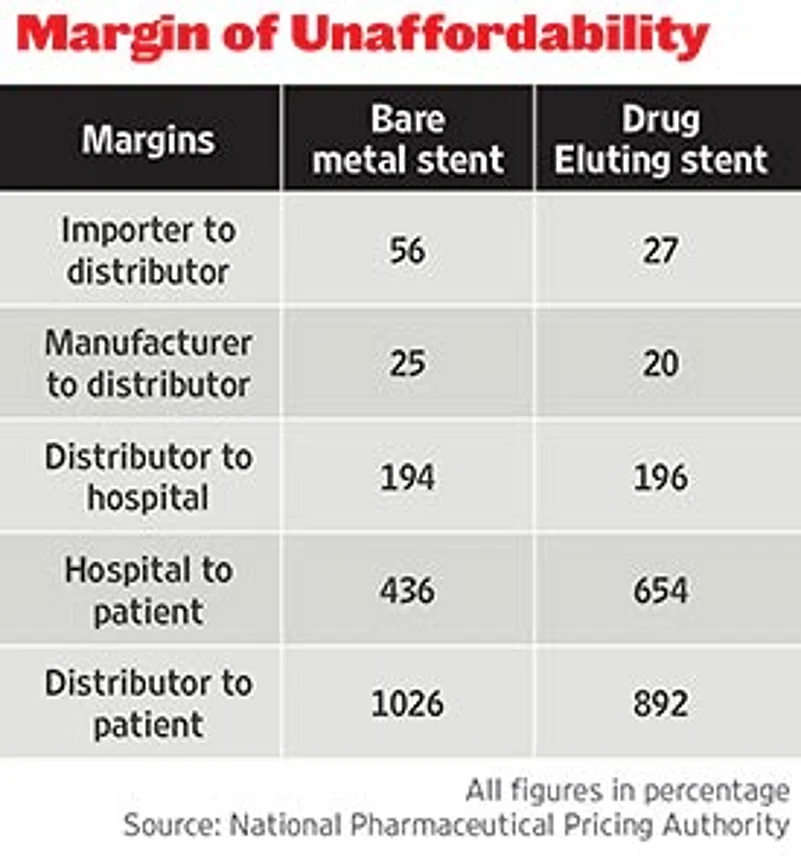

Hospitals sell life-saving cardiac stents at a margin of over 1,000 per cent of their actual cost. This revelation came up in the latest data provided by the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA). It found mark-ups in stents as high as 1,026 per cent of the landed costs, with Rs 67,272 deduced to be the average unit price paid by the final consumer. It’s the first time the government has come out with this data.

Since the order for price regulation of stents was passed by the Department of Pharmaceuticals on December 21 last year, the NPPA has been busy with consultations and data gathering on the costs of different stents—bare-metal, drug-eluting and bio-absorbable. Research suggests the total expenditure on angioplasties is Rs 7,600 crore (equivalent to 40 per cent of the central government’s health budget), of which the largest amount is spent on stents. Bringing stents under price regulation is therefore crucial in making healthcare affordable.

To speed up the process of price fixation, the NPPA has asked all stent-manufacturing companies, foreign and Indian, to submit data of costs involved in manufacturing and distribution as well as maximum retail price per stent. The price-fixation norm for all drugs and medical devices under Schedule 1 of the National List of Essential Medicines—the list of all drugs and medical devices under price control—is the market average method, in which the average of all market costs of drugs sold by different companies is fixed as the maximum retail price.

Outlook’s December 26 cover story Heart for Mart Sake exposed the corrupt nexus between companies, distributors and hospitals, with distributors paying bribes to hospitals and doctors. The cost of each stent, after adjusting mark-ups, could be anywhere between Rs 50,000 to Rs 2 lakh.

The most recent notice by NPPA displays an array of prices for both bare-metal and drug-eluting (the two categories of stents whose prices are fixed by the authority). The memorandum, which shows the landed costs, price to distributor, price to hospital and MRP, clearly depicts the exaggerated costs and mark-ups. According to the NPPA data, while the minimum landed cost of a drug-eluting stent can range from Rs 5,126 to Rs 40,820, the MRP could be anywhere between Rs 40,000 and Rs 1.98 lakh—a trade margin of 892 per cent. “This is data submitted to the authorities by the companies themselves,” says Malini Aisola of the All India Drug Action Network (AIDAN), which works on improving access to drugs. “Despite such visibly high margins, the companies are still fighting for prices to be fixed at a level much higher than the common man can afford.”

Funnily enough, foreign companies have justified such high prices and margins by adding a disclaimer that they do not sell directly to hospitals, but through distributors, and are hence unaware of all mark-ups that occur after sale to the distributor. In the NPPA notice dated January 12, 2017, the listing of prices come with the following note from companies: “The price to hospital are net maximum price across a limited number of hospitals which have entered into rate contracts with the company and the company does not have any visibility beyond these.”

A cardiologist who wished to remain anonymous refutes such claims. He says while distributors are responsible for supplying the stents to hospitals, it still remains the job of companies to negotiate prices and contracts with hospitals. “In most hospitals, you will always find sales representatives of different international companies trying to push their products,” he says. “For companies to say they are unaware of the deals struck by distributors in terms of costs of stents is quite inaccurate.”

The initial calculations from the data received by the NPPA show pricing of stents under price control at Rs 67,272, after it was decided to use price to hospital as the basis for the average of stent prices. This price is much higher than the CGHS price of Rs 23,675. While this was welcomed across the country as a good move, as prices would come down by 50 per cent, the fact remains that stents, even at this price, would remain out of the common man’s reach. Ashwini Mahajan of the RSS-affiliated Swadeshi Jagaran Manch (SJM) says this price reflects the cuts given to hospitals and doctors. “The cost of manufacturing these stents is just a few thousands,” he says. “Calculations made by us suggest that even if you were to add a 35 per cent profit margin to the price of import for different distributors, the price still won’t go beyond Rs 21,881.”

Because of the many confusions in price calculations even as industry groups lobby against price control, a Rajya Sabha committee was formed under BJP MP Prabhat Jha to speak with all stakeholders regarding price fixation. The committee recently held consultations in Bhopal and Mumbai with representatives from civil society, including consumer organisations, and from industry and the government. Rajeev D’Souza of AIDAN, who attended the consultations in Bhopal, says most representatives pushed for price control, with only the industry and a few private doctors taking a different position. “While most people agreed on the need for some sort of price control, the representative of the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) came with a PowerPoint presentation opposing the move,” he says. In fact, the industry has always opposed any umbrella price control for all drug-eluting stents.

The SJM, on its part, has sent a letter to Jha, requesting him to take action and fix prices closer to the CGHS levels. “We have gathered that various stent manufacturers and industry associations have asked for the ceiling price to be fixed on the basis of simple average price at hospitals,” reads the letter, a copy of which was obtained by Outlook. “As can be seen through the NPPA’s calculations, such a price will not meet the purpose of ensuring affordability. Such a faulty methodology must not be used in deciding public policy. We would like to state that there should not be any discrimination between the costs reimbursed to government officials and the prices paid by the public.”

Mahajan, who is part of the team at SJM campaigning for a reduction in stent prices, says that it was met with a positive response from the committee. “We spoke to Mr Jha, who assured us that it was high time to stop such exploitation of the public,” he says, adding that the committee assured him they would work on fixing prices to make stents more affordable. The committee, though, is still deliberating on the matter and has released no final report or recommendations so far. The NPPA is still in the process of collecting data from companies and the deadline is January 31.

The SJM letter is one among many received by the committee. Jha tells Outlook that the ten-member committee he heads is working towards submitting their report on the pricing of stents as soon as possible. “We are currently in the process of consultations with manufacturers, hospitals, middlemen and doctors to properly understand how prices can be fixed justly,” he says. “Our aim is to recommend a price conducive for all stakeholders, especially the public.” Indeed, price fixation would be a futile exercise if it does not keep the interests of the patient in mind.