Even though Robert E. Kahn and Vint Cerf’s efforts had led to something we now know as the internet, it took a Tim Berners-Lee to give us the World Wide Web—a term incorrectly used synonymously with the former. However, users still needed to have access to indexed web pages or websites sorted according to specific queries. The first search engine, Archie, was around, and first-generation web users will remember the likes of AltaVista, Lycos, Yahoo and Dogpile more vividly. But the collective imagination was blown when Sergey Brin and Larry Page came up with Google.

Since the end of 1998, Google has been at the forefront of innovation and popularity in the universe of the general web search engine. The likes of Google are horizontal search engines, trawling and indexing entries according to relevance to provide results. However, the web user’s need for specifics also led to the rise of vertical search engines such as Amazon and our desi Flipkart in e-commerce—a place where a user can now find every product imaginable.

When it comes to the general horizontal web search, Google just needs a crown to call itself king. According to StatCounter, Google had 93.82 per cent marketshare in India in December 2016, while Bing from Microsoft had a 4.7 per cent stake. Statista says Google cornered 94.55 per cent of the pie in October 2017.

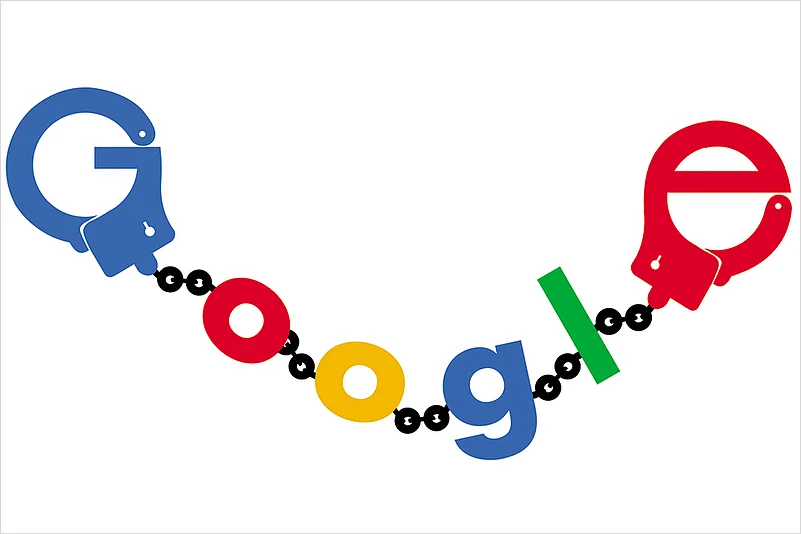

Everyone loves a gentle giant who doesn’t go trampling all over without reason. The initial philosophy behind Google was that it is for everybody—a vast ocean of information where anyone from anywhere in the world can dip in for the pearls he or she is searching for. But what if the giant starts to flex its muscle? That was precisely why Google got a rap on the knuckles in India on February 8, in a case of abusing its dominance. Last Thursday, the Competition Commission of India (CCI) fined Google Rs 135.86 crore for having “abused its dominant position in online general web search and web search advertising services in India”. The CCI said the penalty, calculated at five per cent of the average total revenue generated in the period 2013-15, is to act as a deterrent and “reflect (the) seriousness of (the) infringement”.

In a cover-story in mid-January, Outlook had said an order was expected in the case from 2012 that involved Matrimony.com Limited (formerly Bharat Matrimony) and Consumer Unity & Trust Society (CUTS) as the opposing parties. Last year, the European Union also penalised Google $2.8 billion for breaching anti-trust rules when it came to shopping comparisons.

In a majority ruling of 4-2, the anti-trust watchdog found Google wanting on three counts in its 190-page order. Firstly, there was the issue of ranking universal search results (SERP: Search Engine Results Page on Google) prior to 2010, when “rankings were pre-determined to trigger at the 1st, 4th or 10th position on the SERP”. The CCI found this to be in contravention of Section 4(2)(a)(i) of the Competition Act. The watchdog found Google in violation of the same clause when it came to displaying results pertaining to flights as it deprived users of “additional choices” and asked it to put a disclaimer on the ‘search flights’ option. And finally, the CCI found the tech-giant in violation of Sections 4 (2)(a)(i), 4(2)(c) and 4(2)(e) for imposing “unfair conditions” on publishers, which prevented them from using services provided by competing search engines on account of agreements signed with Google.

CUTS general secretary Pradeep Mehta says he is “happy” with the CCI order and that they would not file an appeal in the case. One takeaway from the order, he says, is that “consumer awareness is important”—the consumer needs to be aware that there are other search engines. Sources tell Outlook that Matrimony.com may file an appeal in the case. In the trademark case, Matrimony.com (formerly Bharat Matrimony) had alleged that the likes of Shaadi.com could advertise by bidding on keywords related to its trademark name, Bharat Matrimony, allowing for its results to come on top when someone Googled Bharat Matrimony.

In the case of search results, Google still allows for the bidding of keywords, making paid results possible, which had caused a contention involving trademarks. Google’s algorithm has been in a state of constant change since 2010, and digital marketers say both organic and paid methods work to trigger results. “With paid, you bid on a keyword, which pushes organic down and the paid page comes up. Otherwise, SEO (Search Engine Optimisation: making a page Google-friendly) can help push it down over time, say over three to six months,” says a digital marketing consultant. There are two ways to ensure you pop up on search results: either you are relevant and popular according to Google-compliant techniques, or you pay for keywords—a bid to “manipulate the rankings”, as the consultant puts it.

The CCI did not find Google wanting on that count. Legal experts and digital marketing experts Outlook spoke to backed the CCI order, some saying it would help democratise the space by increased competition. “The order tries to balance innovation and competition in the online search space, and attempts to make sure the ordering of results on SERP is based on objective criteria, ensuring that the user gets the most relevant results,” says Karan Lahiri, advocate at the Supreme Court of India. “On the trademark issue, the CCI adopts a hands-off approach, while also saying there is no unfair condition that Google imposes when it allows advertisers to bid on trademarked terms. In fact, it is the lack of a condition that enables users to view a broader range of ads and, according to the CCI, promotes competition.”

Manasa Venkataraman, research associate at the Takshashila Institution, agrees, saying the order did take into account Google’s measures to prevent and rectify any trademark infringement. Although the words Bharat and Matrimony “may have been trademarked together by Matrimony.com,” she says, “Google was not wrong in allowing Matrimony.com’s rivals from using minor variations by, say, bidding for ‘Bharat’ and ‘matrimony’ separately.”

Coming to the second count, the CCI asked Google to put a disclaimer indicating that its ‘search flights’ link “placed at the bottom leads to Google’s Flights page, and not the results aggregated by any other third-party service provider, so that users are not misled”. In a recent newspaper article, Rahul Matthan, partner at TriLegal, writes he found nothing illegal with what Google did on that account: “High marketshare and dominance are no longer anti-trust concerns. What is important is the conduct of a dominant market player and whether it is using its dominance to stifle innovation and/or competition.”

According to Venkataraman, the Competition Act is not fully equipped to deal with the digital economy. “The more we move towards a digital economy, the more apparent this handicap will become,” she says. “The minority view in the order was more nuanced, explaining why the majority was hasty in holding Google guilty of abusing its dominant position. It said the onus was on the majority bench to show how Google Flights was foreclosing the market to other players, and in the absence of this being proved, Google cannot be held guilty.”

And finally, the CCI held Google’s agreements with publishers to be “unfair”. Saying the agreements did not allow access to the “online search syndication services market”, the CCI asked Google to remove the said restrictions and pay a penalty under Section 27 of the Competition Act. Lahiri compares this to the DLF case, where the real-estate consortium was asked to pay Rs 630 crore for “unfair” terms in their agreements with buyers. Touching again on the theme of innovation versus competition, he emphasises that the ruling only applies to a subset of online players, who dominate a particular slice of the online market. He adds that the CCI “hasn’t done anything so drastic that it would destroy innovation in the online market”—an argument Google has made multiple times.

Outlook cover, January 22, 2018

Digital advertising consultants, who mediate between brands and the Adword interface, still consider Google the go-to option. “My mind is programmed—my website is in order if it is abiding by the rules of Google,” says one. “The trick is in figuring out ways to go to the top on the results page.”

Believing that the competition law needs to catch up with a rapidly changing digital economy, Venkataraman says the new age platforms may abuse their dominance without “necessarily having a high marketshare”, although the current law recognises abuse of dominance only where there is a high marketshare. “The law needs to catch up with the digital economy since the platforms may have such great network effects that it might cause competition concerns in a way that is not imagined in the law today,” she says.

There may be more ponderous times ahead. Taking off from an earlier reference, the vertical search (as opposed to Google’s horizontal method) may be about to come under the scanner next. When news of the CCI order broke, Paytm founder Vijay Shekhar Sharma tweeted, calling it a “milestone verdict”. “A great hope for Indian tech startup ecosystem. Once you become bigger beyond a size, large dominating tech companies start playing super dirty with you!(sic)” his tweet reads.

A spokesperson from the All India Online Vendors Association (AIOVA), which represents over 2,000 online sellers, tells Outlook that the major e-commerce players, who say they will “take Google to the CCI”, are playing the “same dirty games” on their platforms as well. “When we speak about them, they are not retailers but marketplaces. However, if you open their websites on any given day, you will find either their exclusive product or a particular seller’s product on their homepage,” says the AIOVA spokesperson, who claims sellers have to pay in lakhs for the same advertising spots. “They also give advantage to certain sellers. An informal complaint has been sent to the CCI and they will follow up with a formal one as well. There should be a clear divide on how much a technology company should do if they are getting into all these services using our data.”

That data is the new oil is nothing new. Even the CCI in its order says “it would not be out of place to equate data in this century to what oil was to the last one”. That said, the horizontal and vertical pulls of searches that draw from different needs of the web user may stretch competition and its law in India to the limit. The search for ways to make the Google behemoth more fair and democratic is far from over.