Thousands of traders and manufacturers across the country are grappling with the Rs 50,000 weekly limit on cash withdrawals ordered by the government in the wake of the demonetisation chaos. And it’s nothing short of a nightmare for many. A peek into the informal sector—the best one can manage considering its size—shows most of them are neither familiar with the world of digital transactions nor find it convenient. And surely, that’s not what they desired. Many fear the tight flow of cash may well cripple their business if the money supply is not eased soon.

On its part, the government, in its desire to promote digital transactions, has removed a big hurdle—albeit temporarily—by doing away with service charges on debit card and smartphone transactions. But this move may not be enough to help the traders, contractors and small industries—all part of the informal sector that accounts for 45 per cent of India’s GDP and over 80 per cent of the workforce—resume normal operations.

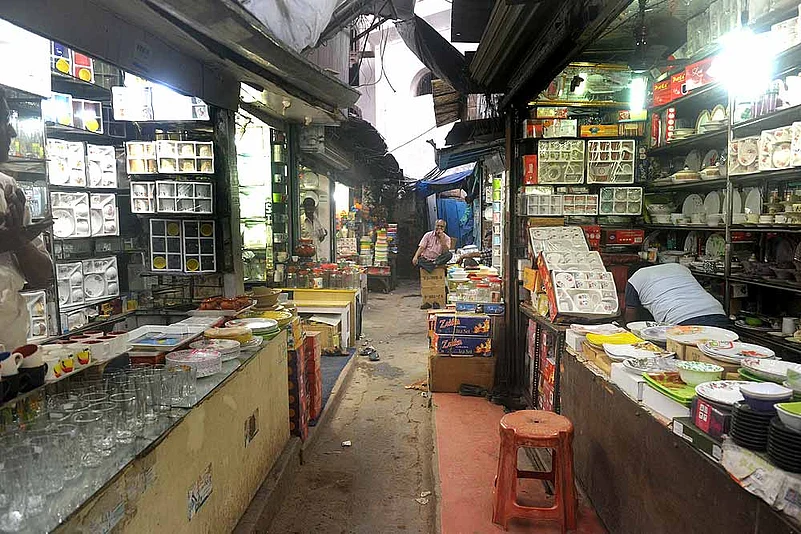

The near-desolate look in large parts of the normally crowded wholesale markets in Delhi, whether Sadar Bazaar or Bhagirath Palace, the largest electrical goods market in Asia, or even at the retail hubs, has its own tale to tell—a story that finds an echo everywhere in the country, whether in Muzzaffarnar, Uttar Pradesh, or the hundreds of small-scale industrial hubs, all of which are operating well below their capacity due to the cash crunch. “Output has been affected, especially in large industrial hubs in places such as Moradadbad, Firozabad, Muzzafarnagar, Panipat, etc. There are over 300 such hubs. Much of the raw materials used by industries there are recycled material. One cannot buy ‘kabadi’ through cheque payment, which means the raw material supply to many units has almost dried up,” says Anil Bhardwaj, secretary general of the Federation of Indian Micro and Small & Medium Enterprises.

As most workers in these hubs are migrants who prefer cash payments, thousands of them are going back to their villages, affecting production. November is part of the peak export season for units manufacturing curios, furnishing, gift items and seasonal wear, so the cash crunch could not have come at a worse time.

Bhardwaj fears many units may be crippled beyond recovery if the total conversion of demonetised currency takes six months as many fear. This is bound to affect the loan-repayment capacity of many units, leading to a rise in bank NPAs.

Praveen Kumar Anand, president of the Federation of Sadar Bazar Traders Association, laments the lack of cash flow, which drives the low-margin wholesale business. It has led to an almost 90 per cent dip in business. “Wholesalers don’t favour a switch to digital or banking transactions,” says Anand. “Our margins are 3-5 per cent on an average. Using a swipe machine or digital payment comes with transaction and rental charges, making it unviable. If the banks take 1.5-3 per cent as charges, how will we survive? Further, even if we want to do so, there are many small traders who are unwilling to transact except in cash for selling or buying products.”

Anand points out that those who are selling without billing have an unfair advantage as the buyers often get swayed by the lure of paying 5-10 per cent less without the tax component. While welcoming the government move aimed at cleaning up the parallel economy, traders were critical of the fact that “not even five paise out of Rs 100 collected as tax gets spent on public infrastructure, which are in poor shape compared to facilities in many countries we visit for business”.

Devesh Rai, founder and CEO of B2B marketplace Wydr, says demonetisation has resulted in “a lot of white money too going out of the system, leading to a working capital crunch. Sales are down across sectors and it will take at least two months to get the liquidity back in the system.”

Reporting 35 per cent dip in ‘cash on delivery’ transactions and overall 20 per cent dip in online sales, Rai admits card transactions can be limiting as there is a threshold for such operations. Currently, many of the high-value transactions are done through NEFT or RTGS, which have higher transaction costs. On top of this, there is a lack of wherewithal, knowledge and infrastructure to handle large volume transactions.

As households try to conserve new currency in hand, given the long queues in front of banks to withdraw money, the hardest hit are the contractors who undertake renovation of homes and offices with their retinue of painters, plumbers, electricians and daily-wage helpers. “Extra expenses related to repairs, maintenance and renovation are being avoided. We are just carrying on with the work in hand. No new work is coming our way,” says A.N. Das, a contractor, who is hopeful that things will improve in two or three months.

Achint Mittal, who owns the Muzzaffarnagar-based R.R. Company, a wholesale business dealing in gur (jaggery), sugar, rice and pulses, hopes cash availability will improve soon as the weekly limit on bank withdrawals is proving to be a big handicap. “Farmers are hit as we are unable to make payments,” he says. “There is already a 50-60 per cent drop in gur production. Even rice-milling work has been impacted as we are unable to procure enough stocks.”

Mittal, who is also president of the Navin Mandi agri-produce wholesalers association, points out that farmers, on an average, bring produce worth Rs 50,000 to Rs 4 lakh to sell in the wholesale market. This is harvest season, so around 400-500 farmers come to the mandi every day. Not having sufficient cash is a major drawback as only the big farmers are able to sell their produce, on credit. The sale of stocks in hand is also moving slowly as even the retailers are not coming forth. Grappling with slow sales at their end, retailers are finding it tough to pay workers and manage other expenses with little cash in hand.

The cash crunch is despite there being sufficient legitimate money in their accounts, wholesellers complain. Even payments made through RGTS are inaccessible due to the withdrawal limit, making many businessmen “almost like beggars”.

“The market is disturbed and business affected as most transactions used to take place in cash,” says Bharat Ahuja, president of the Delhi Electrical Traders Association. “Outstation customers have stopped coming. Even the credit buyers are facing problems with banks not releasing the money in their account.”

Operating from Bhagirath Palace, Ahuja says the desired transition to cashless sales will take time as there is hardly any provision for card payment in around 4,500 shops housed in the market complex.

Indeed, cash transactions, whether accounted or unaccounted, have for long ruled many a business in India—from cloth to leather, gems and jewelry, vegetables and fruits. A rapid transition to digital or online payments seems unlikely even if the proposed Goods and Services Tax (GST) is introduced. Already cash transactions in new currency are beginning to slowly replace what was put out of circulation by demonetisation. Will the government then offer incentives to woo the business class to adopt the digital mode? Or is another surgical strike in the offing?

.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=768&dpr=1.0)