‘Dreaming spires’. That phrase conjured up the genteel aspirations of an older, outbound elite. But think of those desi baroque skyscrapers on the edge of town, and you know the metaphor lives happily in the 21st-century Indian metropolitan suburb. Our cities have changed beyond recognition—the last two decades have seen a feeding frenzy of construction, a permanent flux in the landscape. As urban spaces tried to cope with everyone’s idea of a ‘dream house’, the concrete mixers never stopped churning. Till now, that is.

Look at Noida Extension. It was touted to be one of NCR’s (national capital region’s) most popular areas for housing development. But what you see today is realty’s equivalent of a post-curfew scenario: an uneasy calm. Many apartments are unfinished, construction activity has almost ground to a halt, and there are no signs of the builders trying to sell their pieces of copy-paste architecture.

Whether you like the endless towers coming up everywhere or not, real estate is one of the most prominent pointers of a country’s growth and, along with gold, one of the major avenues of investment for people. But the boom of the noughties is clearly behind us. In the last two and a half years, India’s real estate market has hit a trough. Post-demonetisation, sales have slumped more, despite a further 20-25 per cent fall in prices of ready-to-move-in and resale property, particularly in NCR. On an average, prices since 2015 have fallen 30-40 per cent in most parts of the country due to trust deficit among investors. They are now unwilling to put their money in this once lucrative sector, which is equivalent to betting against future growth.

Despite the dearth of new housing projects in the capital, deals are still being struck albeit at far lower prices than what they would have fetched just two years back. For instance, a duplex three-bedroom flat in a respectable apartment complex in south Delhi’s Saket, got sold just ahead of demonetisation for Rs 2 crore, a big drop compared to a Rs 2.5 crore deal for a similar flat sold in 2014. Similarly, in Munirka, again in south Delhi, a two-bedroom flat in an old DDA complex, fetched Rs 95 lakh as against earlier offered prices of Rs 1.35 crore. Even builder flats are selling in the heart of the city for around 20 per cent less than their peak prices. Across the country, in key cities, unfinished projects and unsold inventory await takers, who are banking on further dip in prices. New laws to bring accountability into the sector have not helped due to poor implementation of rules framed by many states. “The drop in absorption of new projects in NCR is around 70 per cent compared to 40-50 per cent in other parts of the country,” says Samir Jasuja, CEO of PropEquity, a platform for real estate services and data analytics.

“Residential real estate is going through its own pain and has been in decline since 2013,” says Anshul Jain, MD (India), Cushman & Wakefield. “From 2010 to 2012, the market was overheated and many projects were launched nationwide. Prices doubled in three years and reached an unsustainable stage. Many new developers came into the market, but did not have the ability to deliver. There are no end users in the market now as the trust factor has gone away.”

In Mumbai, the slump is largely confined to the outskirts

Jain estimates that most of the available units in NCR are priced 20-25 per cent lower than in 2012 and expects the residential market to remain subdued for the next two years. According to data from real estate consultancy JLL, Mumbai (not the tonier parts of the city) saw housing units’ sales dip by 19.9 per cent while sales in NCR dipped by 7.5 per cent, followed by 15.7 per cent in Chennai and 12.7 per cent in Kolkata. Only Pune and Bangalore bucked the trend and saw a rise in sales of 21.1 per cent and 0.9 per cent respectively. However, prices in most of these places have fallen by 15-25 per cent.

Experts feel there were various reasons for the slump in the residential real estate market, and not all of them apply equally to all regions. While demonetisation led to a big hit in housing purchase as a large part of purchases happened in black money, the unrealistic pricing of apartments played a big role in killing demand. “To varying degrees, the ‘culprits’ were overpricing, the wrong kind of supply and failure of builders to deliver projects on time,” says Anuj Puri, chairman, JLL Residential. “These dynamics conspired to create a major trust deficit among buyers, who increasingly felt that they were being taken for a ride or held to ransom by predatory developers. Unnaturally high prices were often the result of excessive speculative activity, such as what was seen in markets like Mumbai and NCR.”

Simultaneously, high interest rates and lack of sufficient government incentives for home-buyers played a part. Over time, developers have woken up to their own role in deflating sentiment and, in many cases, amended their business practices, the kind of supply they churn out and their prices.

Experts feel the slowdown in residential sales is more or less a nationwide and primarily sentiment-driven phenomenon. With developers realising this and the government and RBI making a concerted effort to revive sentiment and provide real protection for homebuyers’ interests, the market is now picking up again, though very slowly and only in pockets. That said, markets like NCR, where the trust deficit and incidence of project delays were highest, will surely take a longer time to pick up pace.

“Housing prices will only pick up when there is enough demand to justify hiking them,” says Puri. “As of now, there is still a lot of unsold inventory to be cleared and developers will not engage in adventurous pricing until this happens. We are likely to see demand pick up faster over the next few months, primarily because of increased buyer confidence on account of RERA (Real Estate [Regulation and Development] Act).”

Obviously, the unrealistic increase in house prices, especially in NCR and Mumbai outskirts, have played a major part in the recession in the housing sector, causing a huge dip in demand in these two biggest residential real estate markets in the country. “Prices of real estate in Delhi NCR and Mumbai went up significantly even in dollar terms, way beyond income levels or purchasing capacity. The economy did not keep pace as GDP fell from above eight per cent to around six,” says Anshuman Magazine, chairman (India & South East Asia) of real estate consultancy CBRE. “That triggered the fall and sentiment turned negative, leading to a liquidity shortage and low demand. This was prominent across India, especially in NCR and Mumbai, as well as in big cities such as Bangalore, Pune, Hyderabad, Chennai and Calcutta.”

Perhaps NCR has faced the maximum brunt as the fall in prices here has been particularly steep. “There has been a correction of 20-25 per cent in prices in NCR properties in the past six months,” says real estate consultant Pradeep Mishra who tracks markets in north India. “The maximum impact is in Noida where developers had bought land from the Noida Authority on an instalment plan and a large number of them defaulted on their payments.” Recently, the Noida Authority released a list of 91 such builders. Most of these projects are delayed. Another reason why the impact has been maximum in Noida is that most buyers here are from the mid-segment and middle-income group.

The price drop is also visible in east Delhi, Dwarka, Vasant Vihar and Greater Kailash where, according to Mishra, there is a correction of up to 20 per cent. The situation is similar in Gurgaon, while in Faridabad, where there is a lot of middle-income housing activity, the price slump is higher at 25 per cent. The demand here, say consultants, is only in ready-to-move-in properties, while only 10 per cent buyers are interested in projects under construction.

Under-construction flats in Ghaziabad, NCR

“There are no investors in the market, only end users interested in ready-to-move-in projects,” says Hitesh Gahlot, MD of Brisk Infrastructure Developers, which has many projects in NCR, especially in Gurgaon. “The majority of builders have cheated buyers, so nobody trusts them now. As a result, demand in NCR has fallen by over 50 per cent. Prices have fallen significantly. 2013-14 prices are not possible anymore. Prices will remain at current levels for the next two-three years.”

The story is the same in other parts of the country. While there is no major impact on the main Mumbai market, the slump is visible on the outskirts, in areas such as Navi Mumbai and Panvel. “In India, with every major economic reform, people expect real estate to be among the first industries to feel the blow,” says Anubhav Aggarwal, Managing Director of RNA Corp, Mumbai. “Post-demonetisation, the real estate industry has suffered a slump due to stringent policies of loan approvals and the lack of cash flow. Industry has witnessed a huge downturn from buyers of the luxury and commercial segment as overall economic dynamics has gone downhill. Although there has been a minor drop in prices for certain low- to medium-cost housing, there has been no change in the sales.”

Interestingly, Pune’s luxury and super-premium segment houses have not been touched by the slump. In fact, Pune recorded the maximum growth in sales in the country since last year. “We have not seen any slump in the market in the luxury or super-premium segment or in our growth, while RERA, REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts) or demonetisation were being implemented,” says Atul Chordia, chairman, Panchshil Realty, Pune. Bangalore, the third biggest real estate market in India after NCR and Mumbai, also fared better than other markets, though market watchers say residential sales were down towards the end of 2016 and in the first couple of months this year.

“We definitely don’t see a huge uptick,” says Samantak Das, chief economist and national director (research) at Knight Frank India. “From end-March to April-May, the market was behaving much better than in the December quarter. In other words, things are coming to proper shape compared to the previous quarter, but it will still be below the figures for the same period last year.” Like in NCR and other parts of the country, the slight improvement in March and April has been because of easing home loan rates, thanks to intervention by the government. Das finds that developers aren’t pessimistic because interest rates are lower and prices have remained stagnant.

Typically, in Bangalore, houses priced lower than Rs 50-60 lakh sell much faster than higher priced houses. Experts note that there are pockets in the city, for instance in south Bangalore, where there is some inventory pile-up. “At the city level, whatever inventory the market has would need not more than three years of sales,” says Das.

Bangalore, whose real estate sector is largely driven by the IT industry, has typically been an end-user market and, therefore, more stable in terms of sales and new launches. “We have seen new launches and sales dip as much as 50-70 per cent in the past three years in NCR and 30-50 per cent in Mumbai outskirts, but nothing like that in Bangalore,” says Das, who reckons that following the dip in volume after the best years of 2010-11, NCR and Mumbai too probably reflect an end-user market now. “Five to six years ago, if you entered any developer’s office in Noida and Greater Noida, you would see only underwriters sitting there. The investor fraternity, including underwriters, are out of the market now.”

According to V.K. Vijayakumar, investment strategist, Geojit BNP Paribas, real estate goes through an eight-year cycle. From 2004 and 2012, there was a veritable boom in the market—an asset bubble. Black money was also a reason why prices rose sharply during this period when one was able to buy land without a PAN number and both gold and land transactions were opaque, financed by cash transactions unlike investment in the stock market or mutual funds that are transparent. Since then, there has been a decline in prices and volume of transaction because most of it is financed by speculative transactions. Nine out of 10 transactions are speculative, where people are buying to sell when the prices rise. When the market comes down and goes into a frozen state, like now, these speculators vanish.

In Kerala, for instance, land transactions in the past two months have been 60 per cent less than during the corresponding time last year. And that was lower than the previous year. Many developers have not sold a single unit in the past one year, according to reports. In real estate, there is a time correction where you see the number of transactions and speculators decline, while the prices may remain stagnant for five to six years. Another factor behind the Malabar gloom is that non-resident Malayalis are investing less in land, which they used to invest heavily in along with gold. This could be due to declining crude oil prices coupled with job losses, mostly in the Gulf.

“There was a little uncertainty in real estate because of demonetisation in November and December, but that scenario has changed and things are looking up,” says V. Thankachan Thomas, vice-president, Prestige Estates in Kochi. “There might be a small hiccup when GST is implemented, but it should be fine after that.”

In Chennai, where sales have dropped by about 16 per cent over the past year and prices are nose-diving, things are not looking good. Faced with a sluggish real estate market, which had slowed down registration of properties and deprived the state of much-needed revenue, the Tamil Nadu government slashed the unrealistically high guideline value fixed in 2012 for registration of properties in the state by 33 per cent last week. Simultaneously, the registration fee was hiked by three per cent. In effect, to register a property in Tamil Nadu, one has to pay stamp duty of seven per cent and four per cent as registration fee on the guideline value—no net benefit for the consumer, according to Suresh Krishn, Chennai chapter president of CREDAI (Confederation of Real Estate Developers’ Associations of India). “If they had merely lowered the stamp duty by a few percentage points, it would have had a better impact,” says Krishn.

The reason for the muted response is that Chennai alone accounts for over three lakh unsold built-up apartments in the city due to their high valuation as well as non-remunerative rents. “Most highrises along the Rajiv Gandhi Salai (between Chennai and Mahabalipuram), where the IT companies and engineering colleges are located, have merely 60 per cent occupancy. Too many flats got built in the last decade,” points out Mahalingam, a real estate broker.

In 2012, wanting money to service its freebies, the Jayalalitha government tapped two big markets for revenue—liquor and real estate. It hiked the guideline values for properties by 210 per cent, hoping to earn more by way of stamp duty and registration fee. Instead, the high fee only led to the number of documents that got registered fall from 35.18 lakh in 2011-12 to 25.28 lakh in 2015-16. The spike in the guideline value also saw many properties outside Chennai get a higher guideline value than market value, when the reverse is the norm. As fewer properties got registered, the revenue from stamp duty and registration fee in the state dropped from Rs 10,470 crore in 2014-15 to Rs 8,039 crore in 2016-17.

In Calcutta and other parts of eastern India, the situation is equally grim. “The real estate market in going through a slump and it has been difficult for us to retain the kind of activity we were engaged in previously,” says Swapan Bhatta, owner of SPS Construction, one of West Bengal’s most trusted builders. He thinks the downward trend started in 2009, during the recession, and the market never quite recovered.

Bhatta believes a series of factors—uncertainty brought on by recession, fluctuating interest rates and, finally, demonetisation—contributed to the fall in real estate demand and supply. “There has been an overhaul in the way real estate business is conducted and the period of transition is not looking good for real estate,” he says.

Another factor has added to the real estate slump in Bengal. “The prevalence of political ‘syndicates’ has wreaked havoc on the way business is conducted,” says a promoter-developer on condition of anonymity. “Syndicates associated with the ruling party have made it tough for us to procure construction material from any source other than their syndicates.”

Bengal is not among the 13 states that have notified or formulated regulatory bodies on the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act 2016 (RERA) so far. In fact, buyers and consumers who are most likely to gain from RERA are apprehensive that the tension between the state and the Centre will extend to implementation of RERA, which is expected to change the way business is conducted in the sector.

Meanwhile, things have been quite the opposite in commercial real estate. This sector had seen oversupply in the immediate aftermath of the global recession in 2008, but that had eased up in a couple of years when demand started picking up. “The past three years have been fantastic and today there is very limited ready-to-move-in supply in all the top markets across India,” says Ram Chandnani, MD (advisory and transactions services), CBRE, and co-chair of the Indian chapter of real estate forum CoreNet Global. With demand outstripping supply, absorption levels may drop to less than 2016 levels by the end of this year before new development catches up.

A housing society in Bangalore; the city bucked the trend, with sales rising in terms of units sold

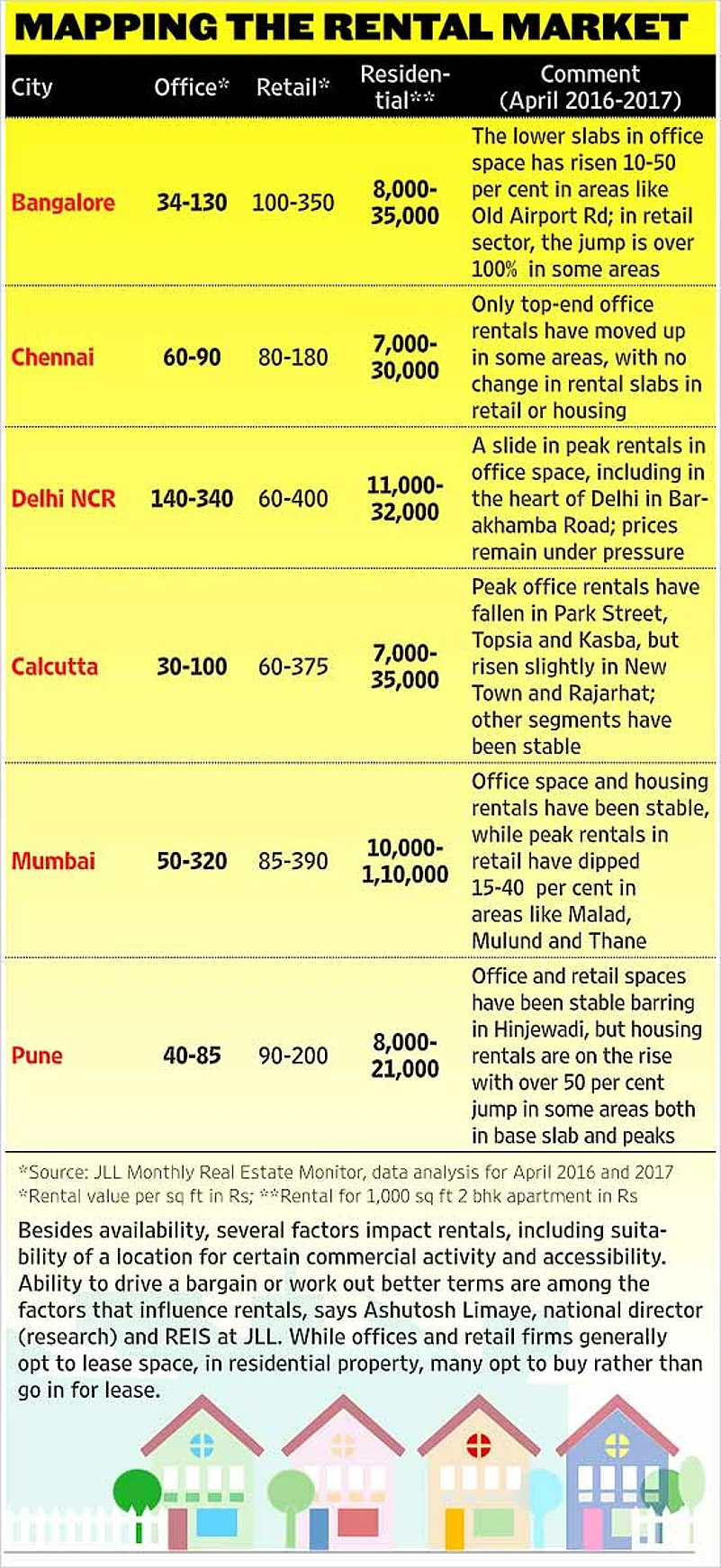

Absorption, which refers to office space occupied in a year, was nearly 43 million square feet (msf) across the country last year, up from 38 msf in 2015 and 33 msf in 2014. For office space take-up, the first quarter of 2017 was one of the strongest first quarters witnessed in the past several years, according to CBRE, with roughly 8 million msf in NCR, Bangalore and Mumbai accounting for more than half of it.

Yet, the commercial real estate market suffered from supply constraints as well as drop in demand from some sectors, which may affect prices. “While activity levels in the first quarter have typically been sluggish, this year’s short-term blip stems from lack of quality available stock,” says Jain. “Demand from sectors such as BFSI (banking, financial sector and insurance) and consulting is likely to remain strong this year, but we see some curtailment from the IT-BPM (business process management) sector. Rampant adoption of automation, resulting in potentially lower hiring could impact space take-up. Moreover, companies may be on a wait-and-watch mode due to the protectionist policies likely to be introduced by the US.”

One thing is sure, residential real estate prices will remain subdued for at least the next two years, with no signs of a pick-up in demand from middle-income buyers—the bulk of the market. The government’s drive against black money will take speculative investors away from real estate to the stock market and RERA will correct a lot of anomalies that the sector has been seeing in the past. After that, it will remain a buyers’ market as the new Act is designed to provide adequate protections for home buyers. So if you have been planning to buy that dream house for long, your time is now.

***

The Great Slide

91 realtors in NCR default on payments

- 25% slump in Gurgaon prices

- 50% fall in demand in overall NCR

- 30-50% dip in prices in Mumbai outskirts

- 60% dip in land sales in Kerala

- 16% dip in Chennai prices

- 3 lakh unsold units in Chennai

By Arindam Mukherjee with inputs from Ajay Sukumaran in Bangalore, Minu Ittype in Kochi, Prachi Pinglay-Plumber in Mumbai, G.C. Shekhar in Chennai and Dola Mitra in Kolkata