It’s part of folk wisdom by now that one of the intended targets of the Modi government’s dramatic strike against black money was the opposition parties themselves. Since parties are seen as entities with a huge stake in the cash economy, they were doubly damned. Suddenly bereft of their hoards ahead of crucial elections, and also handicapped at the rhetorical level—any criticism could be seen as coming from vested interests, and therefore tainted. And judging from the anger, panic and stunned bemusement in the ranks, the missiles had hit home.

A government move on such a gigantic scale, potentially controversial at so many levels, would have normally rallied the opposition parties into a unified, coherent, voluble front. Instead, what one witnessed was a touch of disarray—strangely off-colour Lohiaite stalwarts in Parliament, the budding Nitish-Mamata-Naveen axis broken with two ‘for’ and one ‘against’, figures from the Left breaking ranks to back the move, and the usual voltage fluctuation from the Congress.

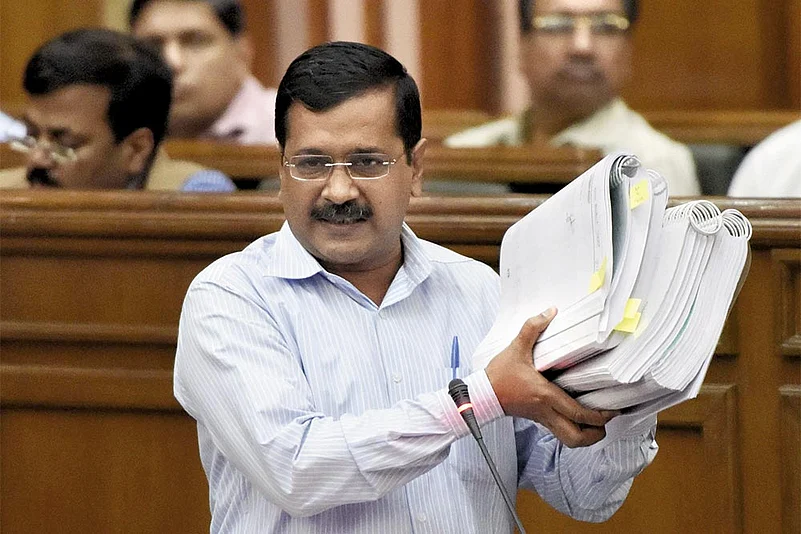

Where ‘mainstream’ parties ceded the space, it was no surprise to see the feisty newcomer, Aam Admi Party, try to take the attack right into the BJP camp with a daring counter-strike of its own. As a party formed in the crucible of the anti-corruption movement, it would have been justified in feeling Narendra Modi had pinched its script on black money in the last year or two. On Wednesday, Arvind Kejriwal sought to turn the tables, if not to reorder the whole furniture—naming the PM himself in an alleged bribery case. It was a typical Kejriwal gesture, full of drama and moment, as he stood up in the Delhi assembly and waved bundles of papers, purportedly from the I-T department, that showed a 2012 text message from an Aditya Birla Group executive, with an entry saying money was paid to the “Gujarat CM”. The referent, Kejriwal said, was none other than Modi.

The Delhi CM had chosen the place and time well. First, the venue: by speaking inside the House, he immunised himself against any legal action. Only the Speaker can take action, if he wishes to, not a court of law. And time: an emergency session of the assembly, a day before Parliament was to meet. Deputy CM Manish Sisodia tweeted: “The biggest expose of independent India. This was planned for 30 September assembly session. Called off because of the surgical strike.” So the new timing only helped tie it in perfectly with all the brouhaha over demonetisation.

As a party that came wearing anti-corruption sentiments on its sleeves, and later evolved its position to try and bring the trading community into its fold, demonetisation had a twin significance for the AAP. Its constituents were directly hurt, plus a lead-by-example call for public morality is precisely what it claims as its distinguishing factor in Indian politics. For a man who once described Modi and Rahul Gandhi as two “faces of the corporate forces”, it made eminent sense to make a strike at the very locus standi of one of its prime political opponents.

Despite the nature of the charge, the AAP cannot bank on any covering fire from other opposition parties. The Congress may tread cautiously for a variety of reasons—not least the fact that its chief ministers too were named in the same set of Birla/Sahara diaries. Besides, the National Herald case is still live, and raids on its spokesman Abhishek Manu Singhvi this week did not leave it exactly smelling of roses. Other parties too may decide to be selectively circumspect. Having raised the battle to this pitch, the AAP has to work hard to keep it there. It would take up the matter with the President, Sisodia told Outlook. A calculated risk, premised on the idea that any intimidation would only make them stronger with the voters.

Outside of the AAP, barring a few exceptions, the opposition could be forfeiting the opportunity offered by all the fury on the streets. The criticism is staying at the rhetorical level, not something harnessed or mobilised politically. Strictly on points, speakers have zeroed in on a viable tactic—including ridiculing the BJP for turning against its own description of a similar move by the UPA as “anti-poor”—balancing this out by taking care not to be seen as pro-black money.

“We agree on total eradication of black money, it influences politics negatively,” senior JD(U) leader K.C. Tyagi told Outlook. “From Lohia to Charan Singh, socialists have always been against black money. But this is an eye-wash. Why is Modi speaking the language of socialists and Marxists when he is close to corporate houses and applying neoliberal policies?”

Raghuvansh Prasad Yadav of the RJD, alliance partner of the JD(U) in Bihar, minces no words. “Aam aadmi mein kolaahal macha hai (there is fury amongst the public). The BJP thought it will gain mileage. But this will boomerang. During Indira Gandhi’s privy purse abolition, people were happy because the kings were targeted. But that jumla won’t work here. This time the impact is on the lower and middle classes. It’s sad. This is the wedding season and rabi season, the farmers need to buy urea, fertilisers. Where will the money come from? They implemented it without planning, without proper logistics, and created total confusion. This will cost the BJP dearly.”

But it’s neighbouring Uttar Pradesh that will be the first testing ground for the politics of demonetisation. The war of rhetoric has already begun. Modi’s recent remark at a Ghazipur rally about “huge garlands of notes” prompted Mayawati to retort that when a ‘Dalit ki beti’ is offered such garland it hurts the PM. The crowd brought for Modi’s rally was “largely from Bihar” and were “paid from black money collected by the BJP,” she said. In contrast, she said, BSP workers “do not offer garlands of black money notes”, they offer small donations as a mark of respect.

The other political grandee of UP, Mulayam Singh Yadav, was guarded in his pitch. “If anybody has fought black money after Lohia, it’s the Samajwadi Party,” he offered, even as he suggested that the Centre keep the policy in abeyance for a week. West Bengal CM Mamata Banerjee represents the other end, having asked for a rollback—unlike Bihar CM Nitish Kumar and Orissa’s Naveen Patnaik who have backed demonetisation, if leaving their partymen to criticise the implementation.

Even outside that, it was a confusing picture. Tamil Nadu’s Jayalalitha’s silence on the issue was remarked upon by commentators, since she has now recovered fully. Sharad Pawar of the NCP, with whom an openly appreciative Modi shared a dais in Pune this week, praised demonetisation (though he’s known to be desirous of a window for cooperative banks). That marked Pawar off in contrast to the Shiv Sena, which swung from praise to condemnation (on the pages of Saamna and in an unlikely grouping for a protest march, with Mamata, Omar Abdullah, Bhagwant Mann of AAP, and a Hardik Patel representative!)

A notable, but perhaps inevitable absentee there was the Left, which preferred to ignore a rare invitation from Mamata to join hands. “We don’t consider Mamata a serious opponent of the BJP. They follow BJP-RSS dictates for the security of their own financial mischief,” says CPI(M) leader Mohammed Salim. The CPI’s D. Raja had a pointed query on the Rs 3 crore deposited by the BJP in a West Bengal branch on the immediate eve of demonetisation.

On specifics, everybody is brimful with questions. Why is the BJP mum on black money stashed abroad, asks BSP leader Sudhindra Bhadoria. “Why did they not instruct private hospitals to accept 500/1000 notes? And do you think a labourer who gets Rs 800 minimum wage has black money?” Some of the flak is centred on the person of Modi. “The RBI should have announced it. But Modi is obsessed with self-glorification,” says Raghuvansh. “People congratulated him and not the army for the surgical strike. He put the foreign minister in the backseat, now the FM is being treated like that.” Tyagi concurs: “It’s not in his temperament to share anything with his party or opposition. The RSS training is ‘nation first, party second and individual third’. But he has replaced nation. The BJP has become the Congress of the ’70s.”