The world of Indian family businesses is undergoing changes, for the better, with several scions exploring new avenues, turning entrepreneur and tasting success. It’s an interesting twist to the contours of family-run ventures that account for around 90 per cent of businesses in India: right from the local kirana shops to farm holdings to multinational conglomerates.

What is spurring this change? Broadly, a spurt in start-ups, advent of new technologies, ever-expanding opportunities, exposure to global business culture and best practices through education abroad are among several catalysts heralding the changes. But is the traditional family business looking favourably at the new businesses? Do they remain standalone? What are the other changes happening in the family?

Vidyanand Jha, professor of organisational behaviour at IIM-Calcutta, explains that family business is a vast category comprising enterprises at different scales of volume, turnover and profit. Across the scale, the newer generation has more formal education, especially degrees from abroad which exposes them to a foreign country and a different work culture.

These youngsters prefer to work outside the family business for some time. “Many are getting into newer areas, more to do with apps or ecommerce or start-ups, which seem to be interesting emerging areas for anybody,” Jha says. If the scales are low, they may altogether drop out of the family business. If not, they yearn for newer domains, to prove themselves, the professor stresses, citing the packaged food business, Guiltfree Industries, started by the scion of the RP-SG Group to drive home his point.

Many family businesses also believe in giving children an opportunity to start their own. Some of them encourage the youngsters to put skin in the game and learn what it takes to start a new business and push it to success. This is a huge learning curve, a confidence-booster. “In today’s age of technology and start-ups, some of the companies have written in their business constitution that even when the children are in college they should be given money to experiment,” says Anil Sainani of Business and Family Consultants, a firm that has been a “mentor” to several family businesses over the past two decades.

About 20 per cent of the progressive families are egging on their children to turn entrepreneurs at an early age, say when they’re in school. Funding for the new venture comes from the family, in addition to backend support. But to limit risks, when the new business is unrelated to the core interest of the group, investment from the family is generally not substantial, experts say. For instance, Puneet Dalmia of the Dalmia Group, which was not into software or internet, set up the joint venture Jobsahead with just Rs 2 crore. And according to market reports, Jobsahead was later sold to US-based Monster.com for Rs 40 crore. “The outside perspectives brought in by the younger generation are proving a medium for change not only in the ways of doing business but also shift in the nature of businesses,” says Nupur Pavan Bang, associate director, Thomas Schmidheiny Centre for Family Enterprise at the Indian School of Business.

In fact, the young, well-educated generation with a better world view and exposure are proving change-makers, including “professionalising” family businesses. “The change has been positive as more families are getting their children better education, which was not the trend twenty or thirty years ago. If you see the Bajajs or Kirloskers of the world, the children joining in are much more educated. So, while they may not have converted into non-family businesses, the family is much better educated,” says Robin Banerjee, managing director of Caprihans India Limited.

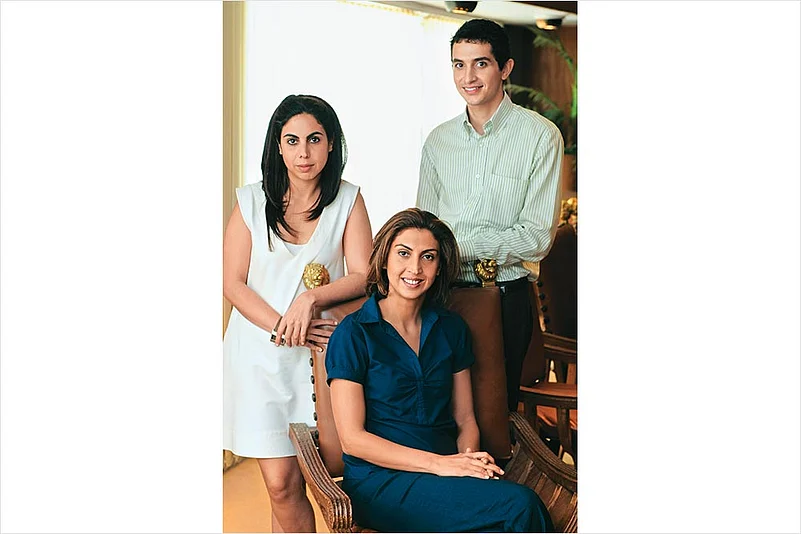

Besides education and global exposure, another major change agent is the breakup of joint families and rise of nuclear families. Further, driven by the shrinking family size with just one or two children, the role of women in a patriarchal business environment has become more important. The scepticism about women running businesses, even if they were highly qualified for the job, is fading fast. Roshni Nadar of HCL Enterprise, Lakshmi Venu of Sundaram Clayton, and Tanya Arvind Dubash of the Godrej Group are fine examples of this changing mindset. Again, many of them have studied abroad.

Roshni Nadar, CEO, HCL Enterprise, with father Shiv Nadar

“In the past, when women were involved in the business, it was all to do with the family foundations and HR roles. But now women have roles right from finance to strategy. And top leadership roles too,” says Bang. There were instances in the past of women inheriting shares but not working in the firm. Well, these happened in the past. Inheritance laws have changed too, allowing women to inherit family businesses and properties. This had a bearing on the altered attitude.

Structures of family businesses have not become simpler. Instead they are taking cognisance of the fact that they are for perpetuity and are thus organising the ownership structure in such a way that it does not matter which generation or gender is managing the operations. They are opting to hold the shares through holding companies or trusts rather than through individual ownership or through Hindu undivided family.

Sainani underlines that though the concept of creating a trust or holding companies like the Tatas and Birlas may be decades old but they had become less prevalent. In the post-economic liberalization society, several new family groups have come into existence. Some of them had not created a holding structure initially, but are doing so now to safeguard the business from family discords over stakes, which can split a business. Reliance Industries is an example. A holding company helps maintain parity between family stakeholders. Another advantage is that it can help raise capital for itself as well as for any subsidiary, and still maintain control.

The creation of a trust helps mostly in countries such as the US where there is a high inheritance tax. There has been a proposal to reintroduce such a tax in India, prompting many companies to preempt the liability. Experts point out that having a trust safeguards against any family member selling stakes in the company to an outsider. The trust thereby protects the business interests of the company.

Another advantage of setting up a trust, according to Bang, is it helps lay out rules and regulations about beneficiaries, including those from the next generations and blood lineage.

Lakshmi Venu, Ph.D., joint M.D. of Sundaram Clayton

It clarifies who gets what in terms of dividends or earnings. It also provides clarity in terms of responsibilities and inheritance rights of family members.

The concept of family governance is picking up in India in the wake of a lot of episodes such as those linked to liquor baron Vijay Mallya, Reliance and Ranbaxy, where family businesses are breaking up or falling. “While business governance issues are very much taken care of by regulators such as Sebi, the stock market and to some extent by analysts and external stakeholders, in the case of family governance structure it has to be managed by the family itself. This means, all family members must abide by certain guidelines. It is not a legal document but a set of best practices which the family thinks all the members should follow,” says Bang.

Such governance rules help institutionalise family values and lay out clear norms for operations: desired qualifications to join the business, duties and responsibilities, and privileges. An example is the Murugappa Group that has a family constitution which is part of the overall governance. The constitution clearly lays out the qualifications required to join any of the listed companies.

Professor Uday Salunkhe, group director, S.P. Mandali’s Prin L.N. Welingkar Institute of Management Development and Research (WeSchool), says every generation has reinvented or regenerated the changes in the thought processes and also the changes in the external environment. Earlier, the next generation would simply start working in the company and in due course lead their family business. “This is not the case anymore, some next-gen leaders pursue postgraduate degrees in business management/finance and are high on networking,” he says.

The IIMs, ISB, WeSchool are among a large number of B-schools that conduct family business programmes at MBA level to help train next-gen entrepreneurs to learn, unlearn and relearn. Not just youngsters, but also senior members of many business families enroll for short-term courses offered by these institutions.

It is not uncommon now to find many scions who believe in starting from the bottom of the pyramid to understand the business better and then climb the ladder. There are others working outside their family business, in India or abroad, before returning to the parent-fold and infuse a next-gen, global perspective.

By far the trend among most family businesses is of patriarchs running their businesses themselves. They don’t trust professionals. There are some willing to bring in professionals. Jha of IIM-Calcutta points out to the tendency of companies not to grow too big or get listed and become answerable to stakeholders. “About why they don’t become lavished entities is that they trade growth for control. Even if they grow, they want to have the total fruits of their labour coming to them. They also mistrust managers’ intentions to work in their interest,” he says.

According to a Credit Suisse report released last year, India has 108 publicly-listed family-owned businesses, the third highest in the world after China and the US. Of late, there have been reports of at least a handful of companies in India wanting to delist. This is in part due to the aversion to hand control to stakeholders outside the family. Among the other reasons, according to Sainani, are that many of the midsized family businesses prefer to remain private and not expose themselves to outside pulls and pressure. Unlike listed firms that have to show results quarter to quarter, family businesses think in terms of generations. Therefore their decisions are a lot more measured and driven by long-term interest, says the consultant.

Given the new challenges and their impact on businesses, many family-run companies are taking help of outsiders. This is creating a demand for more professional managers. Of course they remain vulnerable to being questioned. Sometimes not without reason!