‘Jo mann se hara, woh hara. Jo mann se jeeta, woh jeeta’ (One who loses heart, loses everything. One who is strong, wins), reads a white board on the wall of a freshly painted small conference room of a modest private company in Gurgaon. The woman in crisp brown cotton salwar and black dupatta purses her lips. She’s in distress, her eyes are red as she tries to hold back the tears.

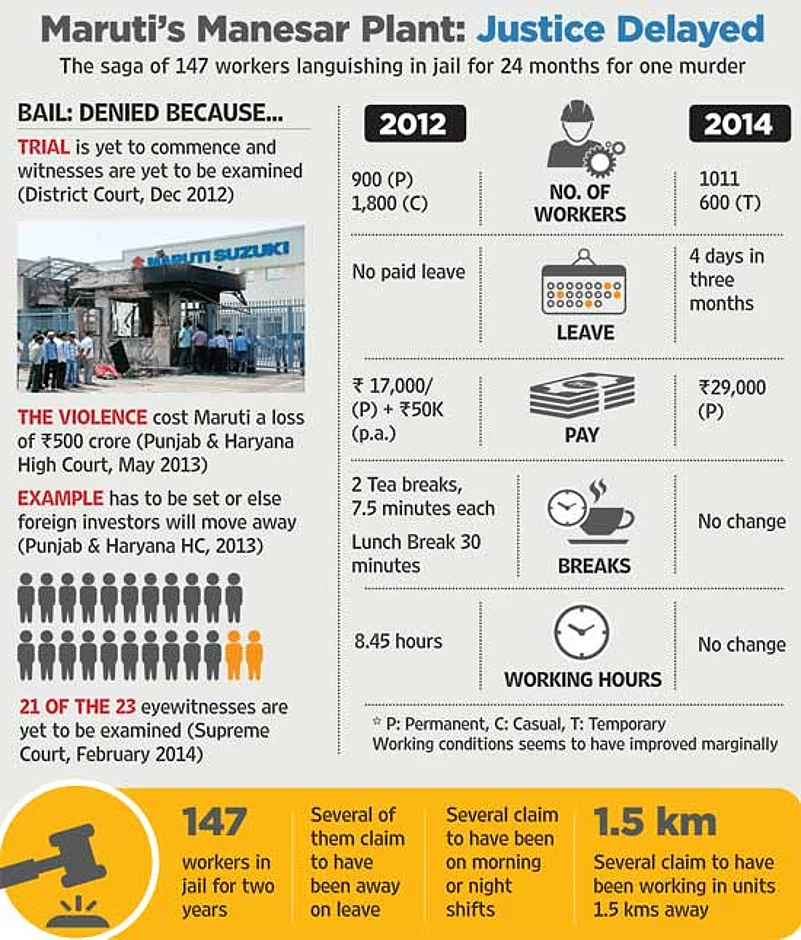

Sushma’s husband is one of the 147 workers of Maruti Suzuki’s Manesar plant who have been in jail for two years now, charged with murder, rioting and criminal conspiracy following the death of HR manager Awanish Kumar Dev in a fire on July 18, 2012, the result of a violent clash between workers and security guards. Special public prosecutor K.T.S. Tulsi says the prosecution hopes to complete examining of witnesses in August. “It is the media that is to blame,” exclaims Sushma. “Did they once give thought to why 147 poor workers would come together to kill one man?” she asks.

The workers have always claimed that they had been fond of the deceased Awanish. He was apparently sympathetic to the workers’ cause and his relations with workers were very cordial, Outlook was told. They had no reason to kill him. So, was it just an accident? And if it was indeed murder, could anyone else have had an interest in eliminating him? The question has not even been addressed by the Haryana police.

Attempts to get in touch with family members of Awanish proved futile. A Maruti official told Outlook over the phone that the company had no information about their whereabouts and weren’t even sure if they still lived in the Delhi-NCR anymore. Surely there would be colleagues and friends of the deceased who would have some information? The queries were stonewalled.

With the chargesheet already filed, and the investigation complete, lawyers say there is no reason for the workers to be still in jail. “The Punjab and Haryana HC stated extraneous reasons of a possible impediment in foreign investment for not granting bail. This is extremely unfortunate,” says the defence lawyer in the high court, Vrinda Grover. While the SC held that eyewitnesses have to be examined before bail is granted, Grover says the prosecution has deliberately withheld eyewitnesses to prolong the case. “Another bizarre occurrence is the sequence in which four witnesses zeroed in on the accused. They have been identified in alphabetical order! Can any judge believe that in a situation of rioting a witness will notice people in alphabetical order? These are clearly false witnesses, the names have been written up from the muster rolls. It’s shocking that this does not alarm a court,” Grover says.

While bail has been granted to the accused even in cases like the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots (death toll 62) and the 2G spectrum scam, the failure in securing bail for even one of the 147 Maruti workers is seen as a sign of the clout the company enjoys in Gurgaon and over the police and the judiciary. “It’s impossible for them to secure justice, unless this case is transferred to Delhi. The police too are agents of the company,” says Colin Gonsalves, a senior counsel in the SC and rights activist.

Families of several accused claim many of the jailed workers were not even at the plant the day the violence erupted. Two boys, Iqbal and Surender, were on leave and did not even go to the plant that day. “Nearly 15 boys were picked up from their rooms in Aliardhanda, a village near Manesar. They were on night shift and their work was to begin at midnight,” says Mahabir, a member of the provisional union of Maruti Suzuki workers, formed after all the members of the former union were put behind bars.

Families of over 10 jailed workers say appointment letters from the company asking them to return to work (when the plant resumed production a month after the violence) had arrived after the arrests. “Even the management doesn’t seem to know who was arrested and why. Several of those who were in uniforms were randomly picked up from the street,” says Dayaram, father of arrested Narender (30), whose traumatised wife is now undergoing psychiatric treatment in a private hospital in Gurgaon.

The defence counsel points to several aberrations that have surfaced in the course of the trial, which leave several questions unanswered. The violence took place in the evening, nearly 12 hours after an altercation between one of the managers and a worker, Jia Lal. (Lal was apparently abused when he protested against an official briefing during their seven-and-a-half minute tea break that morning.)

While the post-mortem report of the deceased manager says the death was caused due to shock and asphyxiation, defence lawyer Rajender Pathak argues that it’s nigh impossible for the workers to have started a fire, as they are thoroughly checked for any items like matchboxes, lighters and cigarettes before they enter the factory, as per a standing order issued by Maruti and approved by the Haryana government. “It is only the top management that is allowed to carry lighters or matchboxes,” says Pathak. Prosecution witness and chief of plant operations, Vikram Khazanchi, accepted in court that officers were allowed to smoke within the factory premises. He, however, denied that workers were frisked before they entered the factory.

What arouses further suspicion is that a police contingent, summoned by the Maruti management in anticipation of violence, was present outside when the incident happened. The statement of Narendra Kumar, asi of the Gurgaon police station then, says the plant security in-charge Capt Deepak Anand had asked him not to send the police inside. When Khazanchi was asked by the court if the security in-charge had been indicted for the lapses and violence, he admitted in court that no action was taken against him. It does beg an explanation on why the management, which claims to have suffered a loss of Rs 500 crore (and according to the defence team duly recovered the amount from insurance companies), took no action against the person who was directly responsible for security.

Defence lawyer Pathak says, “The judiciary is biased. Nearly 100 out of 147 boys arrested were casual workers, who had nothing to do with the union. Demands raised by the union would have in no way affected their salaries or leave. Why would they join the violence?”

The situation had been simmering for a while and it had to do with payments. All permanent workers in the plant at the time received their salary in two parts—a fixed component of Rs 8,000 and a variable component of Rs 7,000, called the Production and Performance Reward System (PPRS). “If a worker took an unplanned leave for a day, Rs 1,300 was deducted from the PPRS. If we took two, we would lose Rs 3,000, on taking more than three leaves, we would be denied the entire Rs 7,000,” explains Mahabir.

Maruti Suzuki, meanwhile, has moved on. Its net profit for the year 2012-13 stood at Rs 23,921 million. Even more ironically, it declared a dividend of 160 per cent compared to 150 per cent in the year 2011-12. The family of Awanish Kumar have either shifted or are behind a cordon. And the Haryana government has been spending a tidy sum every month to pay high-profile lawyers and to keep the workers in jail. Some of them are losing their mind and all of them, in their 20s and 30s, are marked for life. The maximum sentence for rioting is three years rigorous imprisonment and/or fine, if convicted. These young and skilled and semi-skilled workers have been in prison for two years already. Is this what’s called a black hole?

***

Photographs by Tribhuvan Tiwari

Asha 26

Wife of Kamal Singh (28), permanent worker arrested on July 19, 2012

“He was at home by 6 pm and it takes at least two hours to come from Manesar to Delhi and the violence erupted at around 7 pm.”

“The last time I saw him was on our wedding anniversary, three months ago. I wore a new saree and took a new shirt for him. He looked so sick. He had lost so much weight,” says 24-year-old Asha. “He broke down as soon as he saw me, saying he couldn’t stay in jail anymore. He asked me to do something, anything to get him out. But is anything in my hands?” Asha married Kamal in April 2012. Three months later, her husband, was arrested. Kamal was on the morning shift, which began at 6:30 am and ended at 3 pm—some three hours before the violence erupted in the Manesar plant.

When the police knocked on their door the next day at six in the morning, the couple was asleep. “I woke him up and told him some policemen were asking for him. After 20 minutes of talking, they said they’ll leave him in two days after the inquiry got over. It’s been two years now,” she says tears swelling up.

Kamal’s daughter was born in March 2013, seven months after he was arrested. He’s only seen her thrice. “We call her Deepti because he likes the name. We haven’t had the naamkaran yet. We will have it as soon as he is out of jail,” says Asha.

***

Photographs by Tribhuvan Tiwari

Kavita Sundriyal 26

Sister of Amit Prasad (24), casual worker arrested on July 18, 2012

“My brother will come out because he’s innocent. But what about the two years of his life that’s been wasted? His friends are all doing so well....”

She has asked the constable thrice if the books would reach her brother. Thrice he has said yes, but the two books, in pink paperback, continue to lie on the stool beside him. Kavita (26) has just met her brother, Amit Prasad (24), and assured him that the books for him to learn Japanese would reach him. “You either have to do some jugaad or pay to get anything done here. My brother has given money to one of the constables so that he can do him small favours like this. I can’t find him today,” says Kavita. Amit, she says, was dragged out of a shared autorickshaw, along with three others from the plant, all of them in their uniforms. He had completed his morning shift and had taken the auto to IFFCO chowk in Gurgaon, where he would pick up his bike from the Maruti parking lot and return home to Delhi.

“The Maruti management said that those who are in jail are dangerous criminals and hence shouldn’t be let out. Didn’t they check before they employed them? If all these young boys were really involved, they could have set fire to the whole plant and killed many more people. Why would they kill one man?” she asks, fists clenched and her voice quivering. “My brother will come out because he is innocent. But, what about the two years of his life that have already been wasted? His friends are all doing so well in their career; many are getting married. But these boys in jail are now labelled and this punishment they are undergoing will drive them to really become criminals,” she adds grimly.

***

Photographs by Tribhuvan Tiwari

Sushma Devi 29

Wife of Sohan Lal (29), permanent worker arrested on July 20, 2012

“He was arrested at my mother’s place in Himachal. But the police report says they found him in Gurgaon with a rod in his hand.”

“In the FIR there were three Sohans—Sohan Kumar, Sohan Singh and Sohan Lal. My husband’s name is Sohan Lal; but there were two Sohan Lals in the company. The one they wanted was a part of the union and has a different father’s name. My husband’s name was not even in the FIR,” she says.

Dressed in a cotton salwar, vermilion on her forehead and hair neatly tied in a pony, Sushma (29) is wrapping up her work before she can leave for home. It is a Monday evening and she has stayed back longer than usual, to make up for arriving late to office that morning.

She has permission to come an hour late, at the private firm where she works as a data entry operator, every Monday and Friday when she gets to meet her husband in jail for 20 minutes at around 9 am. “I was a Hindi teacher in a government school. I changed jobs a month after my husband went to jail because I could not go late to school after meeting him,” she says.

Sohan Lal s/o Trilokchand was arrested on June 20, 2012, from Sushma’s mother’s house in Himachal Pradesh where she had been since June 16, 2012, after her miscarriage. Her husband left Gurgaon on June 18 after the violence took place and joined them in Himachal. “Sometimes I wonder if my husband’s commited any crime at all. It seems impossible with all the lies the police have concocted. The police have written in their report that they found him in Gurgaon with a door beam and a rod in his hand.”

By Pavithra S. Rangan in Manesar & Gurgaon