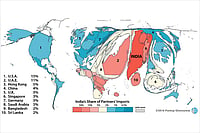

Few could have predicted the boldness with which the Tata Group, once given the opportunity to do so, would stride on to the global scene. By 2003, the year TCS crossed the $1 billion revenue mark and three years after Tata Tea acquired Tetley, international revenues amounted to 24 per cent of the group’s earnings. By 2012, international revenues had increased to 58 per cent. With the United States and United Kingdom as its largest foreign markets, the group bridged the divide between the world’s advanced economies and emerging markets.

In 2011, six Tata Group companies (among 20 Indian companies) were listed on the Boston Consulting Group (BCG)’s list of the top 100 ‘Global Challengers’ from emerging markets. And it’s noteworthy that BCG’s methodology screens out companies “that could only pursue low-end, export-driven models”. The Tata Group includes a substantial proportion of India’s globally competitive, outward looking enterprises. Looking at the group on a per-employee basis, the international focus of the group is also exemplified by the fact that roughly half of the group’s total employment is in TCS, a company that derives over 90 per cent of its revenues from the Indian market.

The Tata Group’s international expansion strategy is also notable for the variety of modes employed. Organic growth in overseas markets (most notably by TCS) proceeded alongside India’s boldest programme of overseas acquisitions (big deals from Tetley on through Corus and Jaguar Land Rover, as well as many more small deals). As an acquirer, the Tata Group cultivated a distinctive buy-and-learn approach, a stark contrast, for example, to GE’s buy-and-restructure pattern. And don’t forget inward deals, of which Tata Starbucks is just the latest example—deals that trade on trust in the Tata name.

With respect to acquisitions focused on brands, Tata Motors is perhaps unique among large Indian firms in having become an owner of a significant luxury brand through its acquisition of Jaguar Land Rover. The success of this acquisition also stands in positive contrast against the generally poor record of companies from other emerging markets buying foreign brands—like the TCL-Thomson tie-up and BenQ’s acquisition of the Siemens mobile phone business. And, as far as acquisitions of critical industrial enterprises go, note how the Tyco deal got the Tata Group into the business of facilitating international information flows, a critical enabler of India’s globalisation.

A final thought relates to Indian national identity and pride in the Tata Group’s globalisation. Going back to its earliest days, one of the main strands in the Tata Group’s history was proving that Indians could do what before only foreigners (British) had done in India. The Tata Group always regarded its role as pushing forward India’s development. Making a run at proving that an Indian group is best positioned to nurture manufacturing in the United Kingdom just might be Ratan Tata’s sweetest homage to the ideals of the group’s founder, Jamsetji Tata.

Pankaj Ghemawat is the Anselmo Rubiralta Professor of Global Strategy at IESE Business School, University of Navarra, Spain.; E-mail your columnist: PGhemawat ATiese.edu