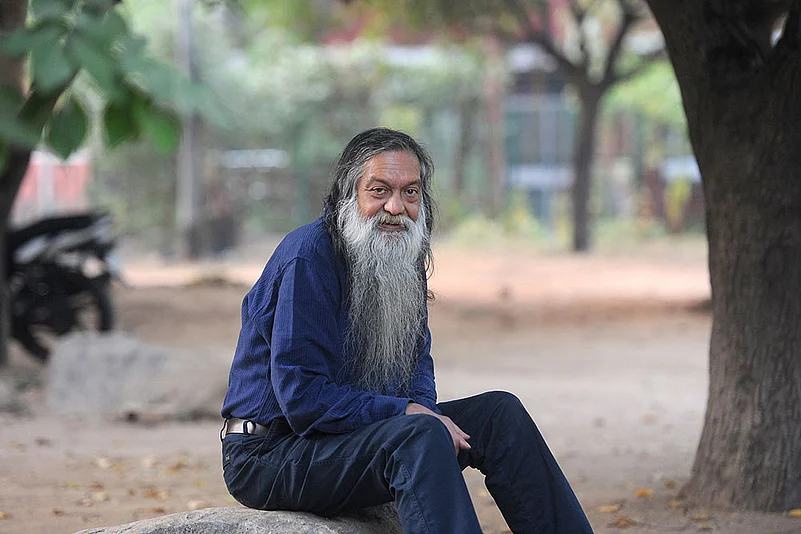

Former chairman of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices, economist Abhijit Sen, in an interview with Lola Nayar, explains that Prime Minister Narendra Modi is planning a greater tax intake buying into the idea of a transition to a cash-less economy. Sen expects a tax amnesty scheme to follow demonetisation.

How do you see the demonetisation affecting the economy?

I don’t know how the whole thing was thought of, but given the fact that 500 rupees is not exactly a very large amount nowadays compared to either the wages—it is two days wages roughly for daily-wagers—or the fact that it is a very large part of the currency in circulation, it must have some pretty strong effect. At least in the short run, the cash economy, which is 50 or possibly 60 per cent (we don’t know exactly what the number is) will be drastically effected. We can certainly expect it to slow down for the first one week, then people will find jugaad to get around the whole thing, but some of the effects are bound to last longer. So essentially in the short run–though I can’t say how short the short run is—there will be the same effect as a sudden drop in demand. Daily wagers will find fewer people willing to employ them because of liquidity crunch. This will be particularly strong in the construction sector. People selling things may also find buyers turning them away saying “Paise nahi hai, baad mein aao” (I have no money, come later) or be forced to take huge discounts, particularly if you want the payment in hundred rupee notes. There will be all sorts of effects…There is a large part of the economy that works on a daily basis—either daily wagers or those who take a loan to buy things to sell. The trend of people relying on money supply on a day-to-day basis is stronger in urban areas than in rural areas. And all that money comes from people who are entirely rooted in cash economy. These are merchants, money lenders, kabadiwallahs, wholesalers and many others. These are people with black money, as a large part of the black money is actually the liquidity for a very large economy. If these people get scared and shut off to fix their own problems, then it will have an effect—which may be for a week or a month…I don’t know how long it will be.

What sort of impact do you see on the rural economy?

The rural area problem is different. Many of them would have savings in cash, so it’s not a liquidity problem, but they need to think of how to convert those savings into something that actually buys things. That is important, but it is not the black money problem. Given the provision to exchange the currency in banks, they may be able to do so by claiming earnings from landholdings and agriculture. Some may need to open bank accounts. The problem will be more for people who are distant from banks and still have 500 and 1,000 rupee notes and may not bother about it and find out much later that they have lost all their savings or at least part of their savings. But that is more of a humanitarian problem than an economic one. The economic one is the sudden squeeze on what is a day-to-day cash economy, which will suddenly see a massive decline in liquidity fuelled by an attempt by some people to cash in on the fact that they might be able to actually provide a service by buying the 500 rupee notes. We are not short on problems but the goal of this whole thing is to take out the black money stocks. But they don’t seem to have thought too much about what flows with that money. The 500 rupee today is a bit like what 50 rupee was when the last demonetisation took place in the 1970s. Since then, prices have gone up about ten times. What the government has done is hit out at what is the most common denomination of exchange. The Rs 1,000 notes may not be as common, but I hardly know anyone who takes out less than 500 rupees out of the bank.

Another problem I see in the rural economy is that this is the beginning of November and the kharif harvest has started coming in slowly since October. This is the time when those who have got the harvest completely in and sold it would have a lot of cash. Most of them would not have put the cash in bank accounts. With so much of 500 rupee notes lying around, when they are told that the currency in their hand is no longer valid and you would have to change it for the new currency, they are bound to be upset.

The government has talked about cleaning the economy of black money. Have past demonetisations helped do that?

No, it has not worked in the past. What it does is—if there is a stock of black money, some of it would simply vanish as it will not be changed into the new currency due to the fear of being caught out. All you are doing is reducing the stock of money without doing anything about the processes which generate it.

Will the attempt to check black money bring down real estate prices as expected?

I don’t see anything changing for most of those who are holding on to property—either not sold or those who have not found buyers or those who acquired property for reselling at a later date. Nothing is forcing them to sell their properties right now. So a sudden collapse in property prices is not going to come from an end in demand. But I am not entirely sure if prices will come down. In fact, they may well go up.

Would you say the move was entirely to unearth black money or was there a political dimension to it?

This suggestion, of a transition to a cashless economy and reduced cash transactions to help improve tax collections, has been floating around for some time now. This idea seems to have been bought into. In the course of things, there might be some notion that there are stacks of cash lying around that can be tapped into through such a move together with the disclosure scheme. Perhaps, soon after this move, there may be an amnesty scheme, which will help the government have a lot more cash. So, more than previous governments, Modi is thinking of improving the tax intake, as he obviously wants to spend more on development in the last two years of his office. The decision seems to have been worked out in terms of not the effect on the economy today, but the effect on the ability of taxes to unearth unaccounted money in some sense. Any move of this sort is bound to have political dimension. As media reports state, it is almost like a ‘surgical strike’, signalling the message of a tough man who has ability to take decisions that ought to have been taken much earlier.

Secondly, it will put political parties that are going into elections in the next four months into a bit of a problem, as everyone would have collected quite a bit of cash and, obviously, they would not have only sau rupay ka (100 rupee) notes. Thirdly, because of the effect on the cash economy, whether urban or rural, for at least a week or even a month or possibly longer, the BJP would be going to the election with the possibility of a memory which is not too good. People might well feel that the government move was not well planned. It may also be a bit like Arvind Kejriwal’s odd-and-even scheme, which was implemented without putting in place a good public transport system.