Performance: 84 lakh employment opportunities every year.

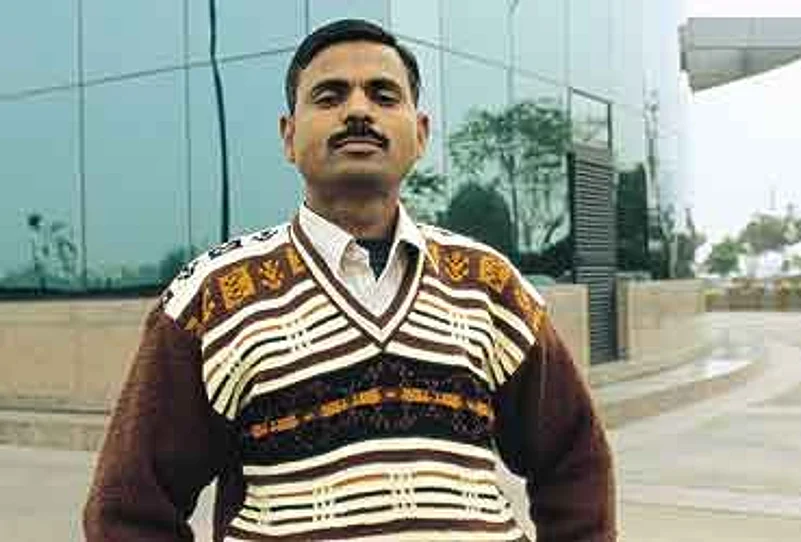

Anil Mohan, 30, lost his job with a white goods maker eight months ago. And he’s getting desperate now. One company offered him half his previous salary and another didn’t assure permanency. But he feels miserable reading that 84 lakh jobs are being created every year. Where are these jobs? Why can’t he get one of them?

Anil’s brother-in-law in Mumbai had applied recently for a railway job. Indian Railways advertised for 20,000 unskilled jobs needing only a school-leaving certificate to be eligible. Among five million applicants that included mbas and engineers, he didn’t stand a chance. The incident caused so much furore that the interviews got cancelled. The railways need to shed some fat anyway.

Sanjay Bhati, 39, lost his Rs 6 lakh-a-year job with a UK-based computer software company about 18 months ago, along with 80 others. "Competing against the best in the business" got this finance professional nowhere. He’s now working at half his last salary, as a consultant with a plantation company.

Amidst all the downsizing, rightsizing, vrss, closures and productivity hikes, the Indian jobseeker’s shadow is lengthening over the economy. Through the ’90s into the new millennium, his number has grown to 7.3 per cent, or 30 million out of a young workforce of 400 million. Every year, one million Indians join the jobseekers’ ball.

On the live register of employment exchanges wait 11 million more, many of them unhappily employed, seeking change. National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) data, however, pegs the number of unemployed at 7.3 million (in 2000). That is the number of open unemployment in the country, which experts say points to the widespread ‘underemployment’, an economic term for working for only food or much less money than deserved.

The truth is that the post-reforms period has been one of jobless growth. Liberalisation raised hopes and salaries in many a profession. New services emerged. But along came competition that sent manufacturing rejigging the share of capital and labour in production. At the cost of labour. Growth became increasingly capital-intensive. Agriculture ceased to contribute as much to the GDP. Thus in today’s India, a new breed of urban youngsters working in cafes take home Rs 5,000 as pocket money, while lack of work forces poor women to offer a day’s work for ten rupees.

JOBLESS, RESTLESS Dunlop factory workers protesting its lockout in Calcutta

Since 1997, the public sector has shed about 15 per cent of its workforce—four and a half million jobs. The private sector has grown in some areas, but it has also shed a million jobs or so. Our employment elasticity (the ability to generate jobs) went down from 0.52 in the 1980s to 0.16 in late 1990s. And the public sector’s—to 0.066. Since the entire organised sector forms only 8 per cent of the workforce, most of the 92 per cent in the unorganised sector, including the 60 per cent self-employed, have to fend for themselves.

The picture would be less bleak in urban areas, but with an increasing trend towards casualisation, even here, the share of regular salaried in the number of workers has slumped to less than 40 per cent. The 57th round NSSO data paint a scary picture: only 43 per cent of the rural and 36 per cent of the urban people are gainfully employed! No wonder that a Planning Commission task force report warned that unless steps were taken urgently, unemployment in 2007 will reach 40 million, with severe socio-economic impact.

Thangamani Ponnusamy Graduate and unemployed for two years. There are 30 million more like him. Only 36% of the urban population is gainfully employed.

Most of the open unemployment and educated unemployment is concentrated in Kerala (21 per cent of workforce), West Bengal (15 per cent) and Tamil Nadu (12 per cent). Our labour force expanded by 1.31 per cent between 1994-2000, but jobs grew at a mere 1.07 per cent. It could be worse. According to a comprehensive national income study by S. Sivasubramonian, employment growth was only 0.82 per cent in this period. Amidst such concrete evidence, the government claim of creating 8.4 million job opportunities creates a ripple of disbelief among many. Says CITU president M.K. Pandhe: "These achievements are all bogus. Jobs are being lost everyday, in textiles, coal mines, steel industry. There may be road-building but public works programmes have almost disappeared. According to NSSO figures, only about 70 days of employment are being generated in the countryside."

NSSO surveys do indicate 8.4 million more people reporting themselves employed over June 2000-October 2002, giving a job growth rate of 2 per cent. But, says Delhi School of Economics Professor K. Sundaram: "These are not jobs, only employment opportunities. A very small segment of this is regular salaried. Government does not create jobs anyway. And it shouldn’t employ more people, especially since it has so many of them unproductively employed."

Planning Commission member S.P. Gupta agrees that the latest NSSO data come out of thin samples and should be used only to indicate a trend. A definite picture would emerge next year after the 60th round is over. But, he points out, they do show that jobs are growing, and the massive fall of the late 1990s has certainly petered out. Crisil chief economist Subir Gokarn too corroborates: "Three developments give us hope. A construction boom—housing, roads etc which would have absorbed many low-wage, low-skill workers. Two, rising consumption of low-end, low-value products, reflecting growing incomes and improving lifestyles of the poorest groups. Three, corporate downsizing is petering out and there is a definite recovery in manufacturing."

Post-liberalisation, India’s job market has undergone massive structural changes. For one, services, especially financial and trade, have become one of the biggest and fast-growing contributors to GDP, generating low-skill but relatively high-wage jobs in cities and its fringes. Secondly, the rural workforce has shrunk, especially among women and children, in favour of, experts believe, education. Third, while agriculture has traditionally absorbed half of the growth in labour force, of late employment has really hit a slump in the sector. Fourth, increasing casualisation of labour has rendered the concept of job security meaningless. All this, significantly, with a consistent neglect of the need to create a labour market, by resisting changes in archaic labour laws. Says Gokarn: "By protecting the interests of the organised 8 per cent, the government is actually denying the basic right of livelihood to 92 per cent." He is right, because if employers are not able to shed jobs during recession, they don’t risk taking extra labour during boom period.

Even the small-scale units, which are big GDP drivers in the US or China, are in India hampered by old regulations, employing only 25 million, compared to 75 per cent of urban jobs in China and 50 per cent of the private workforce in the US. Planning Commission advisor Pronab Sen feels that both manufacturing and agriculture have to grow much faster to allow creation of enough employment opportunities. And for India to turn into a global manufacturing hub, we need at least 10 per cent growth rate in the sector to reach the goal of 70 million jobs in the next 10 years.

In the end, says Sundaram, sustained economic growth is the biggest driver for employment. Jobs will emerge where the growth pattern ultimately settles and incomes rise. Meanwhile, jobseekers get time to adapt to new realities: after all, even the ilo charter doesn’t mention job security as a basic.