A few days back, one of my close friends shared a captivating photograph. It showed Vladimir Mayakovsky's house in the backdrop of the beautiful landscape of Georgia. As I took a look at the particular image, I was struck by the way how they maintained the quaint settlement. In the front yard, a magnificent monument of Mayakovsky stood firmly as an homage to the legendary poet.

My friend shared a few more snapshots of the interior. They showed the first editions of Mayakovsky's books, carefully preserved to entice the curious visitor and take them to the world of Mayakovsky. I was working on a project related to the early days of Nazrul Islam at that time. So this experience awakened a curiosity within me about the homes and workplaces where Nazrul—one of the greatest poets in Bengali literature, a polymath, a musician and a journalist—once resided and worked. Thus, my journey to uncover the essence of his existence began.

My first destination was Pratap Chatterjee Lane. Google Maps convinced me that it was somewhere opposite Kolkata Medical College. Till then I gathered and crosschecked information from a few books indicating that Nazrul had resided in the 7th house of this alley during his formative years. The footpath opposite the Medical College was abuzz with street food vendors, serving food to tired family members of patients and those passing by.

Ground floors of adjacent buildings are now used as shops selling surgical instruments and emergency medicines. I approached the individuals in these establishments, hoping to find someone familiar with Nazrul’s proximity. However, their amused smirks reflected a lack of recognition.

Undeterred, I turned to the owner of a roll shop nearby, Subal Das, and asked: “Can you kindly direct me to Pratap Chatterjee Lane?” In a heartbeat, Das pointed the way with a swift motion of his finger. Following his guidance, I came across a hidden, shanty lane that had no nameplate in front.

After a mere minute of walking, I discovered the dilapidated house, unmistakably numbered 7. Catching my attention first was a signboard proclaiming the Kolkata Municipal Corporation’s classification of the dwelling as ‘dangerous.’ How aptly symbolic it seemed!

Why shall we count this house dangerous? Let us go back to history for a while. Initially, Nazrul took up residence at Shailajananda Mukhopadhyay's dwelling on Ramakanta Street. However, a few days later, a servant in the house refused to wash Nazrul’s dishes upon learning of his Muslim identity.

Although Mukhopadhyay graciously offered Nazrul accommodation at his grandmother's unoccupied house on 20, Badur Bagan Row, Nazrul declined the proposal, opting instead to live with Muzaffar Ahmed, an Indian-Bengali politician and journalist.

The Nazrul-Muzaffar camaraderie came to become especially significant having established their expansive influence. Together, they inhabited various locations, including 32 College Street and 3/4C Taltala Lane. Notably, 32 College Street gained significant popularity as it served as the headquarters of Nazrul's influential newspaper, Dhumketu (The Comet).

This address attracted numerous distinguished poets and politicians of the time. To protect his newspaper from surveillance by the British police, Nazrul chose a separate address, 7 Pratap Chatterjee Lane, for both his residence and office. But soon police issued an arrest warrant against him for an editorial poem written by him namely 'Anadamoyeer Agamone' (On the Mother of Happiness's Advent).

In his memoir (Smritikatha), Muzaffar Ahmed wrote: “The date was November 8, 1922. Comrade Abdul Halim and I woke up in the morning and, after having tea, headed straight to the Dhumketu office. At that time, we resided in Room No. 3 of Chandni's boarding house. The office was located at 7 Pratap Chatterjee Lane, and as I arrived, I noticed that even early in the morning, Shri Birendranath Sengupta had come to write for Dhumketu. Within a few moments, the creaking of shoes echoed in the corridor, accompanied by the sound of several footsteps. The police had arrived, conducting a search of the Dhumketu newspaper office and seeking evidence and the whereabouts of Kazi Nazrul Islam. However, Nazrul had gone to Samastipur and had not been arrested. The police initially sought Nazrul's location from me, but we informed them that he had gone outside Kolkata. At that moment, the police showed us a government order stating that two articles, one titled “Anadamoyeer Agamone” and the other titled “Bidrohir Koifat” (The Rebellion of the Rebel) published in Dhumketu on September 26, 1922, was banned.”

However, Nazrul was eventually arrested from Kumilla (now in Bangladesh) on November 23. According to Arun Kumar Basu, the most authentic biographer of Nazrul, he was presented at a court in Kolkata on November 25.

From Prison, on January 27, Nazrul published his essay “Statement of a Political Prisoner” in the last issue of Dhumketu which was published from the same address.

Nazrul writes: “I am a poet. I have received inspiration at the hands of God to express unrevealed Truth, to embody the intangible Creation. God responds through the poet's voice. My words are manifestations of Truth, of God’s own voice. These words may be stained as seditious, but they can never be traitors to Truth and Justice. That message may be punished at the royal gates, but in the light of dharma, at the door of justice, they stand as the blameless, unblemished, immortal, inexhaustible manifestation of Truth.”

The significance of Dhumketu is that, when majority of the then journalists across India were appeasing the British for Swaraj only, Nazrul, the rebel poet, clearly stated the demand for freedom of his motherland from this newspaper. In prison, witnessing the conditions of co-prisoners, He began a hunger strike on April 14 and continued it for the next 39 days. This incident tormented the intellectual and political activists of Bengal.

In Nazrul’s first book of prose, Yugabani, the name printed as the publisher was Shorotchondro Guha, of Arya Publishing House. The address given for Kazi Nazrul Islam, the author and publisher, was 7 Pratap Chatterjee Lane, Kolkata. Again the government found it ‘dangerous’. The then chief secretary of Bengal wrote in a notice: “In connection with the prescription, we searched the “Dhumketoo” office, the Metcalfe Press and the Arya Publishing House resulting in the seizure of about 350 copies of the booklet.”

A house carrying such a glorious history should be impeccably maintained. However, what I witnessed that day left me utterly shocked. As I entered the ground floor of the house, I noticed a few carpenters engrossed in their work, completely unaware that this very place was once inhabited by none other than Nazrul Islam, the national poet of our neighbouring country.

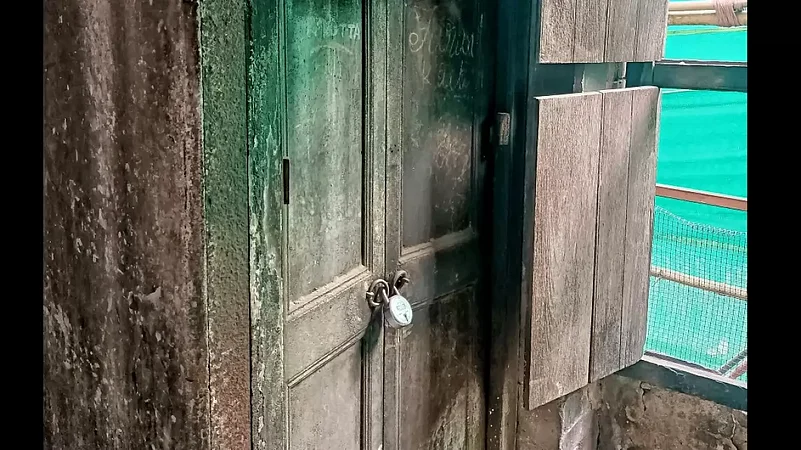

Determined to explore further, I ascended the ramshackle stairs and was greeted by a scene resembling a garbage dump. My prior knowledge from Muzaffar Ahmed's writings was that there were three spacious rooms in the house. I found those rooms veiled in a thick layer of dust, locked from the outside.

Transported by my imagination, I embarked on a journey through time. I stumbled upon an anti-imperialist newspaper office, buzzing with live operations. The editor himself was deeply engrossed in crafting a fiery editorial that would undoubtedly strike the bull’s eye.

I witnessed the rebel poet, Nazrul, reciting his verses with passion and intensity. Bengali intellectuals engaged in profound discussions about the political landscape. However, my reverie was abruptly interrupted by a man questioning my presence, demanding to know what brought me there.

I conversed with the inhabitant of the extended part of the house, namely Kaushik Pal, and assured him of my intention. He acknowledged that he had heard of Nazrul Islam’s association with this place. Yet, despite their awareness, there was a pervasive reluctance among people to take any meaningful steps toward restoring this historically significant house.

When I inquired whether the owner of the house, Abu Sayed, had reached out to the relevant authorities in West Bengal, he evaded the question, unwilling to provide any comment.

Upon returning home, I immersed myself in gathering a few historical data about the house, which I have presented here, and found myself engulfed in a sea of contemplation. What does “Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav” truly signify? Is it the celebration of oblivion? What purpose does the academy, established in the name of Nazrul, serve? Why does our civil society seem so apathetic toward our cultural heritage? Shouldn’t we be ashamed of merely commemorating Nazrul Jayanti every year without taking substantive action?

As I prepared to depart from the premises, driven by the last desire to capture a photograph of the entire house, I ventured into the adjacent plot, 8 Pratap Chatterjee Lane. Suddenly, a vigilant security guard rushed towards me, admonishing me that a promoter was erecting an apartment complex on the land. He sternly advised me against trespassing without proper permission. In a plea, I implored, “Please grant me just a moment, in honor of Nazrul.” The guard promptly called the promoter, relaying my earnest request. The promoter’s brazenly posed question: “Who is this Nazrul?”, left me numb.

Arka Deb is a Kolkata-based journalist and author of the book ‘Kazi Nazrul Islam’s Journalism. A Critique’.