Over the past few decades, Kashmir has seen forced and voluntary migrations. While this diaspora—overwhelmingly Hindu Kashmiri Pandits—are settled in safer lands with better jobs, they never miss a chance to reminisce about happier times at the place of their births, especially to their progeny and grandkids. Oral history, and if possible a rare visit to Kashmir, are therefore the only crutches the next generations have, to make sense of a land now considered dystopian.

Like Delhi-based writer Gaurav Monga, who spent his early childhood in Kashmir, and revisited it for the first time eight years ago, and followed up with regular trips. Monga’s maternal grandparents Prakash and Aroo Soni lived here, and owned the famous Preco Studios—therefore nicknamed Mr & Mrs Preco—on Residency Road in Srinagar.

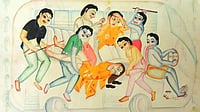

Mr Preco/Monga’s maternal grandfather spurred an era of studio photography in Kashmir where locals and tourists would queue up for solo or family portraits, all dressed up in finery or the typical pheran (Kashmiri attire). The studio evolved with time, from black-and-white images to being touched up with colourful paint. “Such an image is a hybrid between a photograph and a painting, because so much paintwork goes into it. That element of hand makes the painter also the photographer,” Monga explains, while lauding his grandfather’s finesse in both mediums. His photos when viewed from a historical lens chronicle a bygone era of happy families, large parties and lush landscapes with the occasional photograph of militancy or political rallies.

Even today, his grandfather’s photographs adorn the walls of many homes of both local and diasporic Kashmiris, and government and tourist department offices in the region. In fact, a large portrait of Mr Preco still hangs on a wall at the J&K Bank on the Bund. “But no one in these premises knew who took these photographs. Unless there’s a call for submission, we don’t know how many people own photographs that my grandfather took. They [the Kashmiri diaspora] are scattered all over. The only way to archive his missing photographs would be to write about it. Writing can become a replacement for something that is lost,” says Monga, hopeful that the written word reaches those in possession of a Preco photograph to contact him. For instance, a Ladakhi woman who runs a school in Kashmir, with whom he had done a creative writing project, recently messaged saying she has a Preco photograph of her parents. “In the image, you can see the studio, its walnut chairs, and how beautifully my nanahad done up the place, and painted the faces and costumes.”

Given the turbulent times, his grandfather would walk to the studio instead of driving the car. For many years, the family slept on the floor, afraid of bullets flying in through windows. “A lot of our close friends died in crossfire while doing menial errands. One friend got shot by a bullet while buying paneer.” Despite maintaining a low profile, his grandfather was well-known. “He was not wealthy, but by virtue of being a photographer, he sure had some clout as he would take photographs of important personalities, including politicians. It appears he was well-integrated into the fabric of the society of that time.” In his essay for the latest Outlookissue, titled Kashmir Memory Files, the writer mentions that the day his grandfather died, all clubs stayed shut with their flags half-mast, even though he was not a member. Monga’s purpose for documenting his grandfather’s work is also because the studio no longer exists. His grandfather sold it to a close friend, who retained the structural integrity, signboard and brand name, but changed the business. It is now Preco Supermarket.

His grandmother, comparatively, led a more active social life than her husband. “My grandmother was a great teller of jokes, hosted a lot of parties, held gatherings for intellectual discussions, and even ran a boutique for a while. She once saved a guy from being run over by a truck. I also just met someone she had helped when they were stuck in Kashmir. When I visited a restaurant on Residency Road, the staff still remembered what nani ate years ago!”

It was his mother, however, who, over the years, filled in Monga with information about his grandparents and an era/epoch which vanished very fast. She ensured he stayed connected to his Kashmiri roots by furnishing their Delhi quarters with Kashmiri artifacts, books, carpets and paintings, to dish out largely Kashmiri Pandit food as daily meals. “She used to go ballroom dancing and watch movies at cinema halls. I believe Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses first released in Kashmir before other parts of India. There was a very thriving culture in all aspects. I have inherited a lot of Kashmir from her. In that sense, I don’t feel like a complete outsider as there’s a connection that I cannot belittle. But I can’t say I’m from there either.”

During every visit to Kashmir, Monga experiences a “weird, uncanny feeling”. He feels young people like him staying outside Kashmir got aborted from it very early in time, and if things were allowed to grow organically, perhaps studio photography in Kashmir would persist longer. Kashmir still calls out to him, so much so that he wants to buy some land, build a house and conduct creative writing workshops. “I met some very interesting students while attending the Gulmarg Literature Fest as a writer, including a 19-year-old who has written a novel in three volumes. Kashmir has had a vibrant culture of creativity and intellectual discourse all along. Even a small bookstore on Residency Road will have college students wanting to read Nietzsche… So, I want to have some connection to the Valley and the youth, by the virtue of being a writer and teaching there.”

Turbulent years