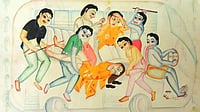

On March 20, 1927, Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar and 10,000 Dalits (untouchables) had descended on Chavdar Tale in Maharashtra’s Raigad district, cupped the waters in their palms and drank all that they could. The iconic moment overthrew the sarvarna (upper caste Hindu) norm that forbade Dalits from accessing any public water tank notwithstanding the Bombay Legislative Council’s resolution to permit the community concerned to use it. In 1950, Article 17 of the Indian Constitution drafted by Ambedkar abolished untouchability.

Yet, instances of sarvarna dominance run rife in contemporary history. On August 13, 2022, mere one week before Rajyashri Goody opened her show at Galleryske in New Delhi, Indra Kumar, a Class VII Dalit boy from Jalore in Rajasthan died. He had been hospitalized on July 20 after his teacher beat him mercilessly for drinking water from a matka (pot) in school reserved for sarvarnas only. In August alone, Rajasthan recorded three other cases of Dalit children thrashed brutally.

Dalit histories are made up of such casteist battles, till recently, widely underreported in the mainstream. People like Goody who belong to this sub alternity—the Pune artist and ethnographer who hails from the same Scheduled Caste, Mahar, as Ambedkar—have taken it upon themselves to chronicle Dalit struggles won and still being fought as inspiration for the road ahead. The Dalit food aesthetic and traditions with its recipes involving ingredients occasionally rotten, half-eaten, and considered deplorable, like rats, form the core of Goody’s art practice, which she tries to immortalize using ceramic, photography, poetry, and installation mediums.

Like her 2017 exhibit titled, What is the Caste of Water?, first referenced the Mahad satyagraha. It showcased one hundred and eight Coupes, Martini, Highball, Collins, and other popular varieties of cocktail glassware containing remnants of the panchgavya, five by-products of the cow—gobar (cow dung), gau mutra (cow urine), doodh (milk), dahi (curd) and ghee—concocted as a purification brew. The glasses symbolised the 108 pots of panchgavya that agitated Brahmins had emptied into the Tale to purify it after the Dalits had ‘touched’ it during the satyagraha. “But technically the sarvanas polluted it… you can die consuming panchgavya,” says the Dalit artist, who holds an MA in Visual Anthropology and is at present completing an art residency at Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam.

This time, her ongoing solo is titled Is the Water Chavdar?—chavdar means tasty in Marathi. “But I am not interested in the water or its taste. Just why animals and sarvarnas can ‘touch’ the water, yet Dalits are still attacked and killed for doing the same. My touch is not any different from yours,” says Goody. Her focus is on the 10,000 satyagrahis who remain nameless and faceless in public memory as there is no photographic evidence of the historic event in institutional archives simply because it had never been photographed! Quite contrary to the widespread media coverage Mahatma Gandhi garnered for his salt satyagraha, his symbolic breaking of the British Raj salt laws at Dandi in 1930.

To rectify the absence of visual documentation of this people’s movement, Goody recreates the Chavdar Tale with 10,000 tiny ceramic mounds arranged in a square, covering almost the entire gallery floor. This water body is cool and inviting, the light dances off the smooth, glazed exteriors of its mounds, and the eye smoothly scans the tapestry of browns, beiges, greens, yellows, whites, and blues… all soothing shades there are to water. Palm-sized and smaller, these ‘hemispherical domes‘ appear like water scooped in cupped palms, then crystallized and upturned to sit on a flat base. Goody calls these domes Buddhist stupas, and there’s one for each of the 10,000 unsung heroes in Ambedkar’s satyagraha. Drop by drop, it became an ocean of people who fought for caste equity. Walking alongside ‘this lake’ is thus intended to feel circumambulatory, where instead of a reliquary stupa, one meditates on the collective bravado of people who reclaimed their right to access public space.

Peculiar to the work a white pillar rising from the ceramic lake, is symbolic of the Kranti Stambh (Revolutionary Tower) in Mahad at which Ambedkar burnt copies of the Manusmriti on 1927 Christmas Day. Onto this pillar, Goody has slathered paper pulp, produced from copies of the Manusmriti; an artistic tradition common to her oeuvre. On a side note, watching her over-three-hours-long performance with Goethe Institut—available on YouTube—of tearing each page of the ancient text into vertical strips, then square chits, building into a pile, meant to pulp and make into laddoos…can prove a gratifying A.S.M.R. experience for some.

The Buddhist markers in Goody’s lake and around Chavdar Tale take note of the religion Ambedkar and his followers converted into as a way out of sarvarna oppression. The setup is similar to her 2019 installation titled Gravel, where rock fragments filled an L shape ‘road’, implying certain sections remain stuck in casteist jobs such as daily wagers at stone quarries, and construction sites, who build modern infrastructure but personally never experience these benefits.

To reposit the historical landmark in contemporary history, the walls overlooking the ceramic lake are dotted with photographs downloaded from Google Maps of visitors to Chavdar Tale. The photographs now exist in two forms of documentation, digital archives, and physical copies. Further, the images, all monotypes, were subjected to experiments such as printing with wet ink and then transferred onto printmaking paper, to appear leaky, ‘stained’, with ink running in places, “to retain the ‘wetness’ while talking about water,” she notes. “We have existed as a community for over a thousand years, but our stories were not photo-documented until 50-60 years ago. But now, these photographic archives are constantly being built. We complain that there’s not much data on minority issues, but there is a lot. It is about where you look. And also realizing that if such incidents had not happened, so many of us wouldn’t be where we are,” Goody observes.