‘Black,’ he hissed, and that meant death. The word emerged roaring from its frothy red cave. Flickering inside, a tongue that savoured and spat out colours like betel leaves. Black. A brittle finger that dug into my chest, drilling deep the officer’s decision that I was to die. ‘Black,’ he said.

Two sepoys – young, panting, eager – immediately dragged me from the line. Both gripped me tightly, squeezing tired flesh with hard hands. They bristled with a need to prove themselves but must have been disappointed, for they were not the ones I wanted to fight.

‘Black.’ The betel-spitting officer had just made the last decision of my life. Several comrades had been granted ‘grey’. That meant they would be tortured, then released near the border. They were to be exiles. And then there were the few ‘white’ ones who were set free. They were seen as harmless.

I had been identified by a lanky teenager: a peon who worked in our district office. He stood studying the lines of fresh arrivals, the shadows of his many betrayals making him look older than his years. But war had aged us all. There were more like him — a mixture of secretaries, office boys, darwans — from districts all over. Who knows how badly they had been beaten, how many close ones cut down before them, to make their heads spin and spin and spin until they no longer remembered what they were facing or where they came from.

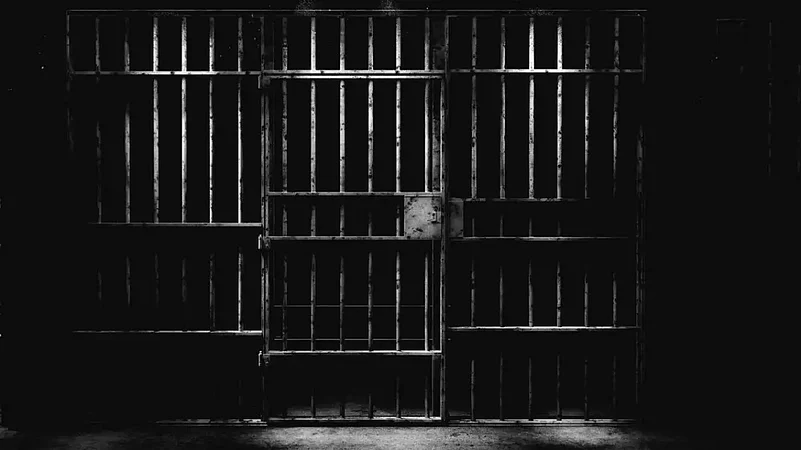

They took me to a black barrack. It was dark inside. I joined lines of men on the floor. Once my eyes adjusted, I saw several familiar faces. A few nodded in greeting. But many just stared at the ground, at empty space, at anything, while their minds churned out the thoughts men have before death. I have had those thoughts for three months now.

We were a silent bunch, with dirty rags stuffed into our mouths. On average, a black prisoner had a few hours to live. There were many ways to die. Sometimes we were just taken outside and shot. But that was no fun for them. They preferred target practice — tied together, we were made to wade through water at night, with torches positioned behind us. This was for officers that needed shooting exercise. Sometimes, we were buried alive. There were more painful ways. Dangerous prisoners were kept for several days, broken bit by bit.

I was not important enough for special treatment. But there were a few among us that would not be let off easily. It must be difficult, having to worry if you could die honourably, if you could die with dignity, not asking, not begging, for the pain to stop. For if you did, you were letting thousands down. Millions. Those that could never ask for their pain to stop, for theirs was that of losing mothers, fathers, children, losing everything they had and being left alive.

But I would die with a smile, because I knew that the more of us they killed, the lower we would crouch among the river weeds, the faster we would tear through the rice fields, and the calmer we would wait on an empty stomach. We would strike just when they cut us. And we would take it until every single one of us was free. Because each one of us knew that there was no punishment, no torture they could mete out, that we hadn’t endured already. Because we were the gentlest people with the hardest resolve.

My turn was six or seven hours away. It did not take long to figure out their system. Approximately every forty minutes, about a hundred of us would be chosen, starting from the front of the tent. The ‘special’ prisoners would be separated. Those sitting near the front had everyone’s eyes on them. For that was how we talked – the gags meant nothing. The human eye can hold so much more, and can speak so much clearer, than made-up words. Strange how many were dying for a language, but we could talk this easily with our eyes.

And we were saying to them, the ones closer to death, that it was all right, that each one of us left would keep fighting, that there was no end, there was no loss too heavy for our freedom, and now was not the time to doubt, now was when we stared at our captors with the same fire all seventy million of us carried, a fire that confused our killers, scared them, and told them very quietly, very deep inside, that they could never win.

When my turn came, they brought me here. About forty of us were chosen to donate blood for their wounded. To donate blood. They were bleeding us to death. Some officer walked in and told us we would be fed later, that we were the lucky ones. I cannot understand why they lied about it, and why they kept lying. You’d think they could tell from the smell in the air that we knew we were dying men.

They tied us down on these benches and strapped a needle into an arm. The needle was connected by a tube to an empty plastic bag. A large plastic bag. And as I watched myself pouring into this bag, I was surprised by how dark my blood was. Maybe it was all my years of struggling and plotting that had coloured my blood so. All the years of straining my body to the fullest, lashing it with thoughts and sights that nobody should face. And to think that they wanted this blood. Didn’t they know that this blood could never be used to hurt our people? That each one carrying away our blood would fall? Just as we were falling. Just as I was now. But there was a difference. I would die terrified, but content deep within. Because I knew I was not leaving. This bag full of me would go somewhere, to someone who would know a little of what it was to be me. And as our killers lost themselves to us, they would lose their war.

But they had lost it from the start.

Excerpted from 'Taxi Wallah and Other Stories' by Numair Atif Choudhury, with permission from HarperCollins India.

(Numair Atif Choudhury was a Bangladeshi author, academic and research scholar. His first and only novel, Babu Bangladesh!, was shortlisted for the Shakti Bhatt First Book Prize for 2019, the first time any Indian literary award shortlisted a posthumously published original work.)