It is October 2013. For the last month, thousands of hopeful singers have flocked to auditions for a chance to be on the first-ever Pakistan Idol, a local spin-off of the British reality television singing competition. Three judges have travelled to cities across the country to meet with these young men and women, and on a warm morning in Multan, a twenty-eight-year-old housewife named Sabiha is waiting for her turn. So far, she has been filmed clutching the show’s poster, submitting her form, touching up her mascara and even splashing her feet in the pool at the hotel. But hours later, she is still waiting with the other hundreds of contestants for her turn to sing for one minute in front of the judges. She smoothes the creases in the crinkly package she holds in her lap — a gift of a silk shalwar kameez for one of the judges — and, for the hundredth time, goes over the lyrics to the song she will audition with.

‘I’m here to wake up the magic in my voice,’ she says to the camera, just as one of the producers has told her to. ‘I love music. Music is my hobby. I eat, drink, wake, sleep, think music!’

And why are you here to audition today? Why do you want to be part of this show? Sabiha gives her best big smile. ‘I want to do Pakistan Idol because I’m an idol.’ Exactly how she’d rehearsed it.

She knows the contestants who can hear her are sneering. What made her so special? Did she think she was the only one chalaak (cunning) enough to bring a gift for the judges? One man had brought dates for them, another flower, and another sohn halva from Multan. ‘My family is a family of paan sellers,’ one contestant tells the judges. ‘My father was a paan wallah, I am a paan wallah, and God willing my son will also make paan.’ Best paan in the country, he tells them, as he fans out the tightly packed emerald green envelopes on a platter. ‘Khaike paan Banaras wallah!’ he sings, his final flourish for the audition before the three red-teethed judges. A labourer skips work for his audition. He cries when they turn him down. He is paid by the day and has nothing by the evening.

Some of the contestants, who have only ever seen the Indian version of the show, come into the room and try to touch the judges’ feet. It was expected, wasn’t it? ‘Poor things don’t know how to behave when they meet a celebrity,’ titters the eldest of the three judges, an actress whom everyone knows for her comedic roles. When one contestant prostrates himself before the judges, the producers scramble to pick him from his sajda. Some children with broken slippers come into the hotel lobby where the contestants are waiting. They don’t want to sing. They are happy to spend the entire day sitting on the red velvet cushioned seats inside the airconditioned hotel.

Others don’t have gifts and don’t care if they make it through. ‘It’s enough for us that we got to meet you,’ they say to the judges. Some of them have flown in an aeroplane for the first time in their lives as they made it past the first round of auditions and were taken to Karachi, Lahore or Islamabad for further auditions. Others haven’t gotten over the thrill of being in a hotel and turning on the taps at any time of the day or night to see a bubbly gush of hot water come forth.

The contestants are in the running to win a car, a cash prize and the chance to record a music album, but everyone knows that the excitement of the show is the real prize. ‘We have to keep Pakistan’s background in mind,’ the actress says when asked about the winner’s prospects in an industry that is all but dead anyway. Might as well give these people a generator, she feels. It would be of more use to them.

Ramsha, a fifteen-year-old contestant from Faisalabad, doesn’t have any interest in the prizes. She has only ever sung religious hymns. She sings songs from the Bollywood film Aashiqui 2 and practises in the bathroom. She is going to Karachi for the next round of auditions. ‘I don’t even want to be the main singer,’ she confesses. ‘I want to be a playback singer. I just want to be famous. I want that the world knows that I sing. I want to walk past someone and have them look at me and think, “Oh she’s that girl, the one from Pakistan Idol.” I don’t care about the prizes. Today you’ll get a prize, by tomorrow it’ll be gone. I want to be famous. That’s why I’m here.’ At night, Ramsha tries to sleep as she listens to her fellow contestants walk up and down the hallways of their hotel floors practising their scales.

Only twelve of the thousands of contestants from seven cities in the country will remain for the final round.

Twelve, Sabiha repeats to herself as she stares at the judges when she is finally called into the room. Only twelve.

After she is done singing, the judge she had brought the gift for, the one whose voice she loves, the one with a tuft of hair dyed crimson like a rooster’s plume, tells her, ‘The tone of your voice is very surely. It has a thin texture.’ She pinches her fingers and rubs them together as if Sabiha’s voice is some fabric a vendor has rolled out for her to inspect. The actress helpfully tries to imitate a voice with a thin texture. Then she trills out what she thinks Sabiha’s voice should sound like.

‘I can’t get past that voice,’ says the male judge. ‘That’s a problem.’

‘What’s the verdict?’ the first judge asks.

‘No.’

‘No.’

‘Can I sing something else for you?’ Sabiha asks.

‘No.’

The cameras follow her as she walks out. She knows what they want. ‘Yahaan pe sirf khoya hee jata hai,’ she says, looking straight into the lens. ‘Yahaan pe kuch paya nahin jata (There is only loss here. There is nothing to be gained).’

She curses the judges. They know nothing about melody. They know nothing about music. They only know who is supposed to get in and who is going to be eliminated. It is all rigged from the start. She turns to face the other contestants, still waiting in those red velvet cushioned chairs. ‘Whatever was already planned has happened here, nothing else,’ she tells them. ‘You should all just go home. There’s nothing fair about what’s going on here.’

She still makes it on TV. The clip of the angry twenty-eight-year-old housewife from Multan was just too good to cut.

Thankfully, it is a clip of another young woman, some 22-year-old girl in Lahore who goes by the name Qandeel, that gets all the attention. Sabiha is quickly forgotten. Sabiha watches this girl prance on camera in a pair of hot pink and black heels, an equally pink pair of tights and a green silk shirt. Qandeel snaps her fingers and dances and sits on the hood of a car bouncing her head to the music playing from her cell phone. ‘I’m a professional model, I do modelling, shoots, brand shoots,’ she explains, in a video recorded earlier in what appears to be her home. She sits cross-legged on a bed with an ornate headboard that has flowers and leaves carved into it. Her cheeks have been rouged and her eyebrows are swiped with too much dark powder. Her hair, parted down the middle, is pinned on each side with a schoolgirl’s barrettes. ‘I love singing so much,’ she says. ‘It’s not just a hobby but a passion.’ (How many of us said this? Sabiha thinks, feeling foolish.) ‘I feel I can be Pakistan’s idol.

‘What’s your name?’ asks the actress judge when Qandeel walks into the room for her audition. ‘Pinky?’

‘Qandeel Baloch.’

‘Okay, I thought maybe it’s Pinky.’ She points to her outfit. ‘Everything is pink.

‘You look so beautiful,’ Qandeel gushes. ‘I always see you on TV but Masha Allah, you look so beautiful.’

‘Feel free to praise him too, or he’ll get offended,’ the actress says, gesturing towards the male judge.

Oh there’s no point praising men, it makes no difference to them,’ Qandeel replies.

‘But I’m sure men must praise you,’ the third judge quips.

Qandeel says she is nervous. She puts on a little girl’s whining voice and the judges cajole her to give it her best shot. But when she finally does sing, she is a natural. She isn’t rooted to that oval plastic mat like the other contestants. She walks forward, beckoning to the judges with her arms, beseeching them with her words, closing her eyes as she sways. She stares straight into the camera. She isn’t nervous. She is performing.

Later, the producers add some effects to that clip. One judge has smoke billowing out of her ears. When Qandeel hits a high note, there is a sound like a spring recoiling. The male judge buries his face in his hands.

When they tell her to leave, she strokes the hair falling from those two schoolgirl barrettes and gives a small smile and says in that little girl’s voice, ‘Don’t reject me, please.’ She pouts. ‘I want to sing a song some more.’

The actress walks over to her and holds her by the shoulders and leads her out. The male judge pretends to cry.

‘You fooled me,’ Qandeel wails to the cameras waiting outside. ‘I told my parents I’m doing this audition and they’re so hopeful now. Now, what am I going to say to them? They will just think, they rejected our daughter.’ She is on the verge of tears, her breath catching on each word.

‘Don’t worry, cheer up, okay?’ the actress says, patting her shoulder. ‘We’ll see you doing modelling someday.’ As she walks away, Qandeel covers her face with both hands and lets out a wail. The show’s host pushes the mike towards her. She turns her back to him, doubling over as she sobs. Her shrieks echo in the hall. There is no one else there. The other contestants have gone away and it is now dark outside. The cameras follow her as she cups her face in her hands, the baby-pink painted nails covering her eyes as she cries all the way out the door.

‘Poor Qandeel has wept off all her kajal,’ the voiceover to the clip would later remark.

Liars. All frauds.

Watch it again. Did you see any tears?

What I did there was my acting. Everything was planned from the start. It’s all bakwaas.

The audition clip went viral. Even long after she was gone, Qandeel’s five minutes on Pakistan Idol would rack up 8.3 million hits on YouTube.

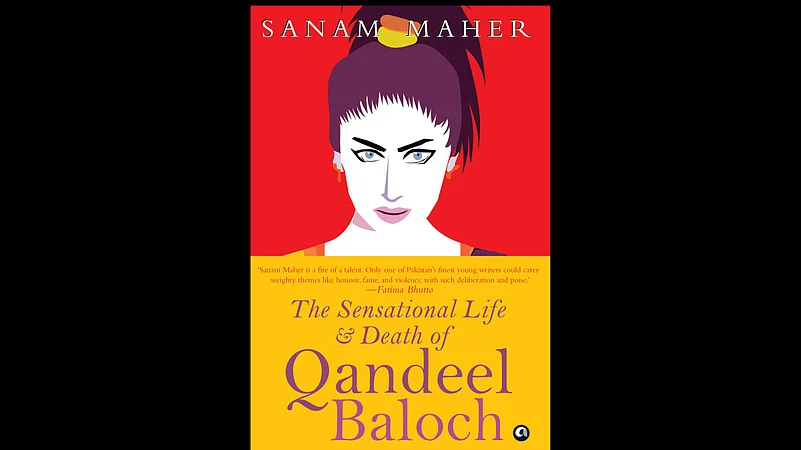

(Excerpted from The Sensational Life And Death of Qandeel Baloch by Sanam Maher, a journalist based in Karachi, with permission from Aleph Book Company)