“I am going to kill my children, wife and myself.” The midnight suicide call in the second month of the pandemic shook Abdul Mabood and his wife Archana Singh. Calling from West Bengal, a father of three shared that his family had not eaten anything for many days. The man on the other end of the phone worked with his friend in a tent house and did not hold a ration card. All attempts to procure a ration card in the middle of an unplanned lockdown went futile. Archana checked her bank account only to find Rs 1,500. All sources of income had dried up for the couple who continued to operate the suicide prevention helpline under the Snehi Foundation. “We immediately transferred Rs 1,000 in their account and then sought for the district magistrate’s help the next morning,” Singh recalls.

The nationwide lockdown imposed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2020 hit migrants, daily-wage earners and lower-income families the hardest, leaving them with no prospects of livelihood and resources to live a dignified life. “Over 70 per cent of the suicide calls I attended during the pandemic and the lockdown were because of financial reasons. The cruel and mindless lockdown pushed people off the cliff both metaphorically and literally,” says Mabood.

Founded in 1994, Snehi’s suicide prevention helpline ran 24X7 but now operates only for 12 hours—10 AM to 10 PM—due to lack of volunteers and funds. Seven out of eight Snehi members work on a volunteer basis, without any salary benefits. All of them have other jobs and take shifts in answering the calls they receive. “Since we cannot give salary to the members, we ask the counsellors to give five hours a week for at least six months,” shares Mabood.

On September 6 this year, the organisation received another suicide call. “A student appearing for the UPSC examinations reached out to us. He had appeared thrice, but could not clear the exams,” shares Mabood, without divulging the details of the caller. He adds that it took a couple of hours to persuade the caller to give a reference of someone in his life he can trust. “These calls are a cry for help. The person on the other end does not want to end his/her life, but they have been cornered to an extent where suicide seems to be the only answer. Our first approach for such calls is to listen to the person while ensuring that they no longer are in the proximity of any physical or mental dangers. We then try to win their confidence and help them reach out to someone they can talk to without any prejudices,” says a counsellor.

30-year-old Nupur Raizada was a dental surgeon before she switched to psychology and now works with Snehi at the Noida-based Father Agnel School’s Bal Bhawan. The doctor-turned-counsellor shares that her own experiences with violence and trauma moved her to work in the field of the mental health sector. “I have spent multiple sleepless nights after coming across deeply distressing cases of gender-based violence at my last workplace. It took me some time to learn to not get too emotionally involved and yet be empathetic when dealing with a person in distress,” she says.

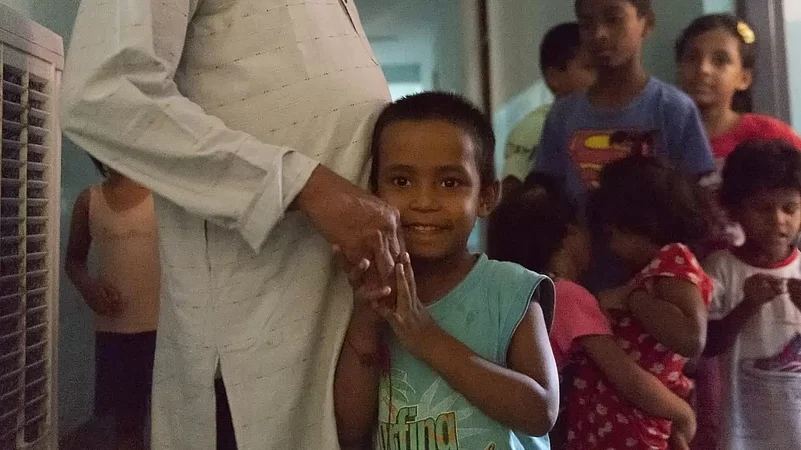

Raizada joined Snehi a year ago and works with kids and teenagers coming from various marginalised backgrounds, who are at a high risk of psycho-social vulnerabilities. “The children here come from families with a history of domestic violence, some are the children of sex workers and many belong to homeless families who live on the streets. Children whose parents are struggling with leprosy or TB are also taken under Bal Ashram’s wings. A number of Kuki children have also enrolled in the past few months since the violence in Manipur,” she explains, as two munchkins living in the Bal Ashram enter her room and embrace her. With about 100 children—between the age group of four to 11—and 110 children of 12 years of age, and above, the counsellor shares that the older residents find it very difficult to discuss their problems, especially boys; socially conditioned to be emotionally inexpressive.

Non-Visiblity and Invisibilisation

The helpline has seen a sharp rise in suicide calls after the Covid pandemic. Between April and November 2020 alone, 298 (7.54%) of the 3952 callers were suicidal. The stigmatisation and lack of information on ‘non-visible disability’ limits the sources of funding for Snehi as well as for other organisations or individuals working in the mental health sector. Funding and government agencies are often inclined to fund projects that help them capture the materialistic impact of their money or resources; non-visible disabilities often get invisibilised as they are inherently not obviously recognisable.

Two months ago, a wary voice asked Mabood: “Did you receive any phone calls from this number?” Mabood found a missed call from the number in the data feed of the organisation’s suicide prevention helpline. “I just wanted to know what he talked about; I am his cousin; and, he died by suicide,” the voice informed. For the next couple of minutes, the caller and counsellor spoke in hushed voices. “He had been having frequent fights with his family on the changing socio-political landscape and had ideological differences. He had tried calling other helplines too, but none of his calls went through.”

Mabood says that a new wave of hate and violence has overtaken the conscience of society, damaging the social fabric of India wherein bigotry thrives. The extent of polarisation has left no human space for disagreement and free expression, giving rise to the politics of “Us” and “Them”, and isolating people. “We have received a number of distressed calls from young people, who have had regular fallouts with their families and parents because their families have become very polarised due to the ongoing hate wave in India. This is creating a void in people’s lives, where they cannot express their emotions openly and are being pushed into loneliness,” says Mabood.

In 1997, Snehi became a pioneer in the Indian mental healthcare sector when they introduced the concept of pre-and-post result counselling helplines for students appearing for board examinations to cope with stress and anxiety. “At that time, the Indian media mocked us,” recollects Mabood, underlining the lack of sensitivity and stigmatisation of mental health issues.

Prejudice and Marginalisation

Meanwhile, the deaths of two students by suicide of Dalit students in just a span of two months in IIT-Delhi has brought the role of institutions into focus to take adequate measures for students struggling with social prejudices and mental health issues. In early August 2023, the Minister of State for Education, Subhas Sarkar, revealed in Parliament that in 2018 and 2019, IITs recorded eight cases of suicide, which decreased to three and four in 2020 and 2021. The number jumped to nine in 2022. By September 2023, the number of deaths by suicides in IITs has already reached eight.

Multiple calls by Outlook to IIT-Delhi’s counselling services went unanswered. While the helpline goes cold for most calls, a few IIT-Delhi students, on condition of anonymity, share the distrust factor with the authorities and administration. “I have personally never approached the helpline due to the fear of being outed, since I have seen it happening with my batchmates and seniors,” says a student. On September 3 this year, the administration invited student and faculty bodies for an open house discussion in light of the suicides of two Dalit students on the campus from the same department and batch. During the session, a student shared that they were made to wait for four days for an appointment with a counsellor, despite repeatedly clarifying that they were at a very threatening and vulnerable space at that time.

Counsellor and retired engineer, Prabhakar Gupta, says that an identified counsellor enables the identification of the person seeking help. “We continue to live in a society where any mental health issue is seen as a problem and the person trying to deal with them is branded as the problem. Due to the fear of being branded in institutions, or losing their job in workplaces, people evade seeking an appointed counsellor.” Gupta also adds that merely a degree or certificate does not make someone an expert in understanding human emotions.

Raizada, Mabood and Gupta highlight that books are not enough to understand human behaviour and emotions. The extent of mental health complexities is multifold—from families and societies to institutions and politics. Unless the multiple layers of issues that exist in society—patriarchy, casteism, religious polarisation, classism, body shaming and hate-mongering—are not systematically challenged through the discourse of mental health, the problems of suicides and mental breakdowns cannot be resolved. Raizada also emphasises the need for empathy instead of sympathy while engaging with someone with stress and trauma, to end the culture of victimisation, which often prevents survivors from coming forward with their stories.

“You never tell someone struggling with stress or trauma that they have a problem, because they are not the problem—their environment, surroundings, culture and family are. I have studied and worked with machines and electronics all my life around the world, a human being is far more complicated than any machine,” adds Prabhakar Gupta.