“A political and aesthetic work of extraordinary originality, quite unlike any other in the long, often turgid and hopelessly twisted debates that have occupied Palestinians, Israelis, and their relative supporters…With the exception of one or two novelists and poets, no one has ever rendered this terrible state of affairs better than Joe Sacco.”--Edward Said, Introduction to Joe Sacco’s Palestine

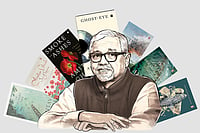

“What we are seeing in Palestine is the attempted annihilation of a people,” says Joe Sacco, acclaimed Maltese-American journalist and cartoonist. Sacco, author of several graphic novels including Palestine, Footnotes in Gaza, Safe Area Gozarde, Notes from a Defeatist and The Fixer, is on a brief visit to Delhi. In conversation with Seema Chishti of The Wire at Jawahar Bhavan on November 11, the soft-spoken cartoonist told the packed auditorium that he, like many others, finds it overwhelming to process the images of the Gaza war flooding TV screens across the world. The war has been going on for about a year now. The violence, unrelenting. “We have to ask: what are Palestinians feeling?” says Sacco. “How long can they go on? How long can Western governments keep shying away from calling it a genocide?”

Sacco spent time in Palestine in 1991 and early 1992 during the first Intifada, interviewing Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. He had gone to Palestine hoping to write a travelogue, but his reporter’s instincts kicked in once he started travelling. When he went back home to the US, he wrote and drew Palestine, a nine-part comics series, which won the National Book Award in 1996. Heartfelt, disquieting, skillfully sketched, and stamped with Sacco’s trademark humour, Palestine is considered a classic of graphic non-fiction. Sacco travelled again to Palestine and immersed himself in the lives of people in Rafah and Khan Younis before writing Footnotes in Gaza (2009), which spans 50 years.

Through conversations with ordinary Palestinians, it excavates the truth behind the massacre of 111 Palestinian refugees by Israeli soldiers in 1956. He documents the everyday violence people suffered in Bosnia in The Fixer, War’s End and Safe Area Gozarde. Paying the Land bears witness to the impact of colonialist policies on the Dene First Nation communities. In Kushinagar, Sacco shines the light on the lives of Dalits in India’s Kushinagar, and in his book set in Muzaffarnagar, UP (slated to be published in English next year), he traces the effects of violence in electoral politics on the lives of citizens.

“I prefer to call myself a cartoonist,” says Sacco, whose first love remains cartooning. “I wanted to make people laugh so I got into comics and then it became more serious. My work is best described as comics journalism.” Sacco completed his BA in journalism from the University of Oregon in 1981, but he wasn’t happy to be a straight-out reporter. He doesn’t subscribe to the thinking that journalism is all about “objective reporting” because subjectivity comes into play the moment a person sets out to report. Combining his love for cartooning with his training as a reporter, he eventually managed to find a means to get as close to “human facts” as possible. His graphic novels are a way of “clawing his way to the truth”.

“Gold-standard American journalism pulled the wool over my eyes,” says Sacco, looking back on his younger days. He “grew up thinking Palestinians are terrorists” because Western newspapers and TV news only talked about Palestinians in conjunction with violence. “The other side of the story; about what Israel was doing and the long history of the conflict was missing.”

Sacco’s parents, who belong to Malta, lived through a horrific war themselves. When he was growing up, they would share their life stories with Sacco, helping him understand the scale of suffering ordinary people in conflict zones come to bear. Sacco realised how crucial it is to understand a place’s history because it puts things in context and helps you to better decode the present.

“I love Sacco’s books because they give you information without overwhelming you,” says Yohan Sharma, a teenager, who had waited patiently at Midland Books in south Delhi to get signed copies when Sacco stopped by at the store. “He goes to places like Palestine and Bosnia and draws the people he meets there as they are,” says Sharma. “As a reader, I get to see these people and enter their lives. Sacco is a great story teller and he makes the world feel more connected.”

Whether he is telling the stories of people in India, Palestine or Bosnia, Sacco remains an unobtrusive presence, and lets his characters speak in their own voices. He often makes an appearance in his books—and draws himself as a nondescript man, an observer who doesn’t hold strident positions. Sacco is no fence-sitter, but he steers clear of polemic, and does his drawings and his concise text do all the talking.

His visuals give readers room to imagine, to come to their own conclusions. Political writing and debates often involve jargon, dense arguments and theoretical propositions. Sacco on the other hand, emphasises the human element, presenting reality through the eyes of a living, breathing, sentient artist. He is unafraid to let the “seams of journalism” show, to demystify the process of reportage, to acknowledge that the person doing the reporting processes reality through his/her own filters.

“The world is getting more and more violent,” says Sacco, specifically referring to the relentless war on Gaza. “The American order is abhorrent and it has gone too far, for too long. I don’t know what will replace it though,” he adds, calling on journalists, cartoonists and satirists to debunk conventional narratives. “So many stories are being crushed and there is a lot of misinformation out there,” he cautions. “Real journalism is a calling, a vocation. Truth telling is a challenge. We have to keep at it.”