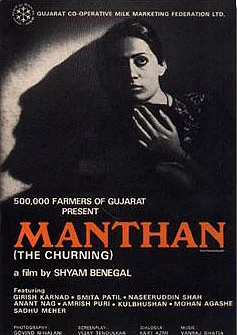

A restored version of the Shyam Benegal film ‘Manthan’ was recently showcased under the Cannes Classics segment. Originally released in 1976, it was meant to depict the transformative effects of the cooperative movement known as Operation Flood that would eventually make India the world’s largest milk producer by the end of the 20th century. As an unabashed celebration of an initiative undertaken by the central government, ‘Manthan’ was in many ways a propaganda film. Yet, it wasn’t uncritical nor was it an unsubtle and ham-handed panegyric that refused to present anything other than a straightforward black-and-white narrative.

In 1965, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri asked Dr Verghese Kurien to replicate what he had done with Amul all over the country. The National Dairy Development Board (NDDB) was formed, and Dr Kurien was put in charge. This led to the ‘White Revolution’ or ‘Operation Flood’ which aimed to form cooperatives which would give greater control and agency to farmers by making them own part of the business. Benegal who had made ads for Amul had also made a documentary on ‘Operation Flood’. ‘Manthan’ is also quite well-known for being a crowd-funded film. Benegal had calculated a budget of 10 lakhs and Dr Kurien asked the approximately 5 lakh members of the cooperative to contribute Rs 2 each. This was not only in keeping with the broader principles of the cooperative but also ensured the film’s commercial success. Everyone who contributed turned up to see the result of their investment.

It's difficult to not call ‘Manthan’ a propaganda film. It holds up a government initiative as the only means of emancipation from ancient structures of exploitation. It also promises hitherto undreamed of political and economic agency along with the tangible advantages of ownership. Nevertheless, Benegal’s treatment of his subject is part of his larger process as a filmmaker. ‘Manthan’ follows ‘Ankur’ and ‘Nishant’, Benegal’s first three films that are set in rural India and deal with themes of feudal oppression and acts of defiance and revolution. ‘Manthan’ is therefore as much about a newly independent nation with a long-entrenched history trying to come to terms with modernity as anything else. The title is significant because it refers to the mythological story of the churning of the ocean which brought forth both good and ill. It sums up Benegal’s attitude in the film.

He sets up the semi-feudal hierarchies of oppression primarily through Mishra (played by Amrish Puri) who owns a private dairy business, and the high caste Sarpanch (played by Kulbhushan Kharbanda). These two form the political and economic nexus of power and work to sustain an exploitative system that bleeds the farmers dry. The effects of the cooperative are seen through two characters who represent the ones most oppressed or marginalized – the strident Bindu (played by Smita Patil), a woman in a fiercely patriarchal community, and Bhola (played by Naseeruddin Shah), who is both Dalit and an illegitimate son. Bhola is an outsider on account of both his birth and his caste and his simmering barely controlled rage is symptomatic of everyone like him living in unequal and abusive communities. These are social settings whose oppressive structures have deep roots and long histories. The ones in power have more than one way to maintain their ascendancy over the poor. In the film’s third act, the Sarpanch and Mishra in their desperation conspire to burn down the farmers’ homes and then offer them shelter and help. It allows them to reassert a paternalistic relationship which they remind the farmers will not be forthcoming from the cooperative people. Manohar Rao (played by Girish Karnad), the man in charge of the cooperative, is almost entirely representative of the ideals of liberal progress and education. He is sent packing after having been falsely accused of rape. Those in power are extremely reluctant to give it up. When the Sarpanch loses the election his bafflement at this impossible turn of events is a good indicator of how deep-rooted these relations of power are. The idea of the cooperative might sound fantastic on paper, but it will have to deal with the complicated ground realities. Bhola refers to the cooperative as ‘sisoty’, which seems to suggest that endeavours of this kind will have to adapt themselves to the local ‘accents’ of a place.

Bhola’s arc in the film is decidedly a blueprint of emancipation. He is extremely suspicious of Manohar Rao’s antecedents at the beginning, but he benefits more than anyone else in the film from the ‘sisoty’. He quickly understands that he stands to gain something he or his ilk never had – economic freedom and agency. He therefore becomes its greatest champion. When the Sarpanch tries to woo them back after burning their homes down, Bhola with increasing ferocity and passion tries to remind them what the ‘sisoty’ means to them. His greatest lesson however comes when Manohar Rao leaves, and he runs after the train in desperation. The message is clear – there can be no replacing one authority figure with another. Bhola is distraught but he soon understands that agency comes with personal responsibility. At the end he shepherds the farmers into depositing their milk at the cooperative offices. He finds a leadership role and prefigures a revolution of greater import than the final acts of ‘Ankur’ and ‘Nishant’.

Bindu is the other side of the coin. She is fierce, articulate and leads the rebellion against Mishra. At the beginning she is responsible for the first movement of the farmers towards the cooperative. Yet, her voice and her leadership are contingent upon the fact that her husband isn’t around. The moment he returns, she is relegated both physically and metaphorically to the cloistered domestic space. Her husband takes away her economic agency by killing her cow and she is used by the Sarpanch to level accusations at Manohar Rao. Benegal makes it very clear that for all its promises, the cooperative cannot do anything to help Bindu. She soon becomes an inarticulate pawn in the machinations of the men in her community. Her absolute transformation suggests that women in the shadow of patriarchal structures are but a shadow of their real selves.

In ‘Manthan’, Benegal offers a nuanced and layered view of the implications of introducing something like the cooperative in societies that have such long histories of caste-based and gendered exploitation. Most propaganda films offer a simplistic binary view of the good and the bad. They discourage plurality or questioning of any kind. Benegal’s films have over the years received funding from the state and sometimes as in ‘Arohan’, he has found it difficult to avoid being propagandist in effect. But in ‘Manthan’, he reorients the art of the propaganda film so that even though it pushes a narrative it simultaneously holds it up for critique.

Arjun Sengupta is an Assistant Professor at St. Xavier's College, Kolkata. He has written a biography of Soumitra Chatterjee, and his monograph on Shyam Benegal will be released soon.