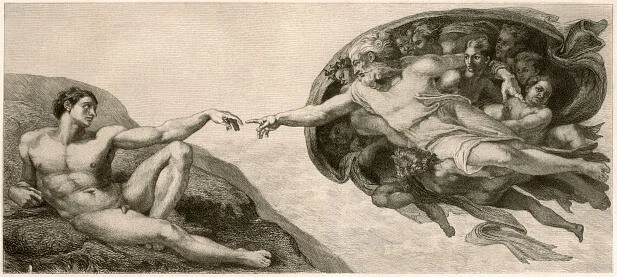

When contemplating a painting, one is compelled to ponder its essence. What truly constitutes a painting? Is it merely a convergence of brushstrokes, hues reflecting the seasons, and the endless toil of a creative mind? John Keats declared, "A Thing of Beauty is a joy forever," suggesting that art unveils the profound thoughts of its creators. Amidst a phenomenon of centerlessness in the post-modern world, the complexities of Art and its role in remembrance are significant. The dynamics of art and memory now lie at the intersection of fragmented perceptions and fluid societal norms. The dynamics of truth in art lie at the crossroads of perceived reflections and societal norms.

Plato, in The Republic, famously asserted, "The tragic poet is an imitator, and, like every imitator, is twice removed from the king and from the truth." This perspective suggests that art distances us from reality. However, works of art have often challenged this notion, drawing us closer to the core of human experience. For instance, The recent "Canvases of Hope" exhibition at Triveni Kala Sangam in New Delhi, featuring the works of the late bureaucrat and artist Niranjan Kouli, illustrated how art can serve as a window to myriad opportunities and reflections. Rather than distancing us from the present, these artworks beckon us to engage deeply with current realities.

The significance of art in addressing historical and painful subjects cannot be overstated. Art has provided a portal into understanding narratives like the Holocaust and the partition of India beyond the immediate pain they caused. Michael Rothberg in ‘We Were Talking Jewish: Art Spiegelman's Maus as "Holocaust" Production,’ observes “by situating a nonfictional story in a highly mediated, unreal, 'comic' space, Spiegelman captures the hyperintensity of Auschwitz.” This blend of unreal and real elements creates a unique representation that bridges memory and historical truth.

Similarly, Oral Historian Aanchal Malhotra’s work on the Partition of India, through her Museum of Material Memory, underscores how art and material culture can preserve personal and collective histories. This repository traces family histories and social ethnographies through heirlooms, collectibles, and objects of antiquity, offering a tangible connection to the past.

In literature and other forms of art, the relevance of art in everyday mundane life is a constant issue. In an ever-changing, fleeting world, art stands as a testament to the endurance of human memory and experience. Dr. Shernaz Cama, Associate Professor in the Department of English at Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi University, asserts, "The one thing that doesn’t change is human nature. Art reflects human nature and therefore holds in itself the values of humanity. It links past, present, and future through the human subconscious—the anima mundi or storehouse of symbols that are reflections of life and nature. You can call it the permanent truth or morality or art." Art endures, bearing witness to the multiplicity of truths. It remains subjective, reflecting diverse interpretations shaped by individual human experiences.

In our post-truth world, where artificial intelligence can create so-called "truths," art stands at the crucial intersection of memory and information. It serves as a beacon of authenticity in a landscape where genuine human experience is increasingly questioned. Dr. Avishek Parui, Associate Professor (English) and Faculty Coordinator, Centre for Memory Studies at IIT Madras notes, “In a sense, we have always lived in a post-truth world, with knowledge and memory subject to manipulation through various media, from pamphlets and the printing press to the internet and AI. Ancient epics like the Mahabharata, with their irony and paradox, and Samuel Beckett's theatre both illustrate this. Art, too, reflects its time, as seen in Leonardo da Vinci’s treatise on using colour to depict pain.”

The "Alienation Effect," coined by German playwright Bertolt Brecht, complicates the role of art further. This technique presents familiar contents in an unfamiliar way, preventing direct empathy from the audience. In today's social media world, where everything seems to affect everyone simultaneously, this technique is particularly relevant. A seemingly controversial portrait of King Charles or an Indian fashion designer making headlines at the Cannes Film Festival exemplifies both otherization and familiarization. It feels as though everything is happening in the corridor where the third wall is continuously broken and rebuilt. As Parui poignantly notes, “Art today, shaped by AI and algorithms, continues to highlight the blurry lines between truth and imagination, remembrance and forgetting, reconstruction and projection. Each era believes its challenges are unique, a form of narcissism. In art as in literature, liminality is all.”

At its core, art is personal—an expression of the artist's vision through their hands. If seeing is imitating, then lived realities coexist with the imaginary. In the dance of time, art transcends the boundaries of mortality, weaving an everlasting mosaic that outlives its creator. In this ever-evolving postmodern world, art remains a beacon, illuminating the intersections of memory, truth, and human experience. By engaging with art, we navigate these intersections, exploring the depths of human nature and the truths that endure through time. Art, therefore, is not merely an escape from reality but a profound engagement with it, offering insights that remain relevant across ages.

Arpita Chowdhury, a New Delhi-based writer, poet, and journalist, possesses a post-graduation diploma in journalism from the Indian Institute of Mass Communication and a degree in English Literature from Lady Shri Ram College for Women.