EPISODE 1:

This conversation is between two ghosts who live in cracks and roam old/ancient buildings. One speaks, while the other listens. They know they are extinct, but not what they must do with their extinction. They are storytellers to each other until they find other ghosts and the spaces inhabited by them. If they know the residents, either living or gone, they narrate their stories, full of anecdotes, aside from an autopsy of character. If they are unknown, they invent. They often confuse spaces and people.

Ghost 1 (almost murmuring, then rising): Do not speak, do not breathe, walls do not breathe, ghosts do not breathe. When they do, there are no sounds. No, breathe heavy. Let your words wave against the bricks to let them know we are here. Not existing, but here like ether. Like these dark spots on this wall. Each blot, is a year dead. To let them know we are the fossils for the future geologist. That the dead are the future of the ones alive. That in the end, only time travellers live. Once we had a body. Bones as hard as this wall; flesh like glazing tint, our feet crushed stones. All that gone, we are sunk in this puddle of time. After losing their body, ghosts inhabit concrete spaces. Don’t be silent. Speak to me. No, be silent, listen to me. I don’t remember the last time words left my mouth. I am only a mouth now; the body leaves slowly, very slowly after death. It wasn’t like this in the olden days, when there were abundant open spaces. We could hold on to our full bodies; the way we lived was the way we lived when we were dead. Now, there are either buildings or owned vacant spaces. We cannot reside on their lands. We do not trespass. It is also against the physiognomy of ghosts. To adjust to smaller spaces, our bodies began shrinking. Some are hands now, legs, breasts, or intestines–we chose to be heads. Not all of it functions, though. The unused parts keep forgetting their purpose, my hair, for instance, or my sense of smell. The dark speckles you see are the blood of termites and worms that lived here before us. In a way, we colonised their country.

Every time we yell, there are splits and clefts on the wall. This wall is ours. This home is ours. We sleep here when we need rest. It used to be a temple or a holy monument, we don’t know. But after we started residing here, it became renowned as the ‘Speaking Wall’. Estranged lovers would come and whisper their secret into these cracks, our ears. Archaeologists heard our incoherent mutterings and wanted to break this down. The government barred them. Sometimes religious scum can save you, especially if you are dead. This is the tale of the wall. It is time to leave, till we are back again, till we are gone again. We are in search of other ghosts; we are afraid for each other. What if one of us vanishes one night? It doesn’t take much for ghosts to disappear. Sometimes, they evaporate when the wind is high. Who will listen to our stories then? Who will tell us, ‘No, we are not alone?’ So…we visit old structures, rooms, terraces, chairs, lamps, and doors, and we narrate our pieces, our chronicles, and histories of people, or fabricate entirely new ones. Someday, they will say, “We are here. Can you hear us?”

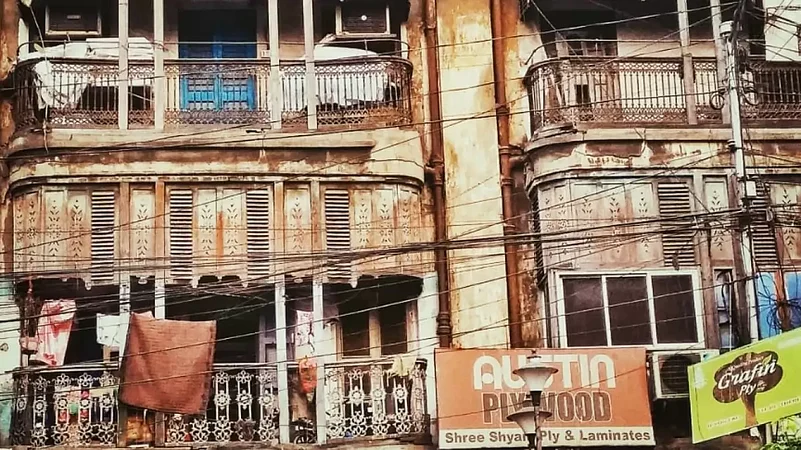

Ghost 1 (sound of wind): We move like shots in cinema. In the last scene, we were in the holes. In this one, we are the ones holding the lens, stretching our bodies, bending our eyes, and breathing in the smoke and grime. I know what you are thinking. That we should be in a darker space, quieter, not even birds, not even the flitting of birds. One can only tell stories where nothing stirs. I know. I can hear you think. But all dead things possess a shared ground of silence. Once we, who once lived, and things, once inhabited, die, we are gifted a strange wordless language that is older than civilisation, older than the first vertical man, older than the world itself. It is the language of objects. The way a stone speaks to a stone or insects pray to the sun. We hear things without end, for everything has a voice; everything just speaks and speaks and speaks. The world is a Babel of things gone. What is the Arch saying? It says it has form, structure, radius, and vertical supports; it says it has a shape. It says we have none. But formless, shapeless, it can still see us. The way it sees grilled windows, rectangular doors, semi-arches, and people barely living in that red faded building. Out of all the things that vanished, this is what we needed—contours. “How would you understand patterns and moulds, when you have none?”

First Arch: 1849. The year they imagined a single vaulting arch built inside this mansion. Let us not name the owner; names will have religions, religions will have gods, and people who believe in gods do not believe in ghosts. Human hands looked after me; this knowledge is sufficient for my account. All of them are dead; the sons and daughters of this family, now haunting other places. Some in desiring freedom, some in jails, and others in a natural way, down to the last light. Only the poet entered me and jumped over to somewhere. Few who escaped this city are far away now, plotting and scheming to demolish the walls, to raise glass arches, or convert this into an antique spot for lovers of the archaic perhaps. Sometimes I wonder how it would feel to be part of antiquity, to be a collector’s item, to be seen as a relic, a prehistoric document.

About the poet. They didn’t find his body. It was not what they said that he took his life. I know. He just wanted to be on the other side. And he thought I was the gateway, the opening to the cosmic mysteries. For days, he did not leave the chair. A wooden chair; three feet away from my wall. Days dissolved into nights, and nights into days. In winter, he would tremble and look at me with sinking eyes. All summer, it was the grating sound of nib over the paper. Page over a page, the sketches of this one Arch and poems on different parts. One on the keystones, one on the springing line, one on the yellow paint, another on the white, the pink, the black, the green border divisions, and one comparing me to the post and lintel, to the corbel arches, to the Roman rounded arches, the intersected pointed arches, the Syrian horseshoe arches, and catenary arches.

Finally, all that physicality gave way to the intangible forces of nature. For hours, he would ponder over my shape. Whether I resembled the grail, a womb facing the heavens (he thought I gave birth to the gods), the organ which in dreams he entered a man and emerged a child, or was I the mouth of the mansion. At age 27, I gave birth to the gods not in a trance anymore. Entirely awake and aware, he climbed the edges, the way he used to when. His legs balanced against a mild storm in the skies. His eyes were turned upwards. He touched everything that was me. My solid frame melted under his warm blood. For moments, I was as shapeless and colourless in life and love as you are now in death and decay. And then there was a leap. He did not fall down; he rose up like angels, and expanded like clouds till he was gone. I imagined him getting scattered all over space. I imagined him invading the storm that was intensifying, and that my poet was falling down on me as rain and entering my mouth as the winds. I imagined because arches cannot mourn, things do not mourn. When you mourn, you cry. When you cry, there is water. If there is water, who will save us? Waters melt us, and we evaporate. Here was a man who loved and slept neither with a woman nor with a man. There was a man who heard the sounds of objects and fell in love with one of them. (Silent)

Ghost 1: As soon as their stories end, they return to their sleep—a long rest on silent beds. We depart without a farewell song, like one leaving home on a moonless night. Each meeting is the first. Each meeting is the last. Our meetings hide our deaths in departures. We are dying of pain…No, it doesn’t pain at all, and we cannot die anymore. The longer I know you, the more my heart turns into the wet mud. You sit there clawing it and making your pagan idol there. So, I leave. I leave. We leave you alone with your memories. Everyone who remembers is a poet. To another arch then, before the night is heavy and things wane again.

Columns and arches, more arches than columns, columns more than arches, arches fusing into the columns. Are you awake? Are your eyes closed? One side forever in darkness, another too much in light, when there is light. One eye in the light, another in the shadow, and the semi-circular middle half illuminated—an immense penumbra. Perhaps you sleep like gods, one eye endlessly opens on the world and things that crawl and scream on the surface.

Second Arch: Where are you?

Ghost 1: Our heads are in the shadows, with their back against the second column. Light burns us. But we are looking. We are here to listen. We see a little hole convulsing. It’s your mouth. You will speak now.

Second Arch: Press your ears against the lines of these columns. What do you hear? It’s the music of children—so many that I lost count. Hiding behind these columns, hopping over the light, avoiding light, and landing on the shadows, them too like you. Their sounds in these slabs. On happy days the kind father would place the child on his lap and teach her numbers. “Count the columns,” he would say. “Now, the patterned petals on the arches.” On other days, the cruel father would punish the son, “Stand in the sun till you faint,”, “Your back against the pillar till your legs are numb.”

An artist needs solitude. You meet yourself in solitude, they say. How do I do that? With so many voices inside, how do I do that? When I speak, it’s always with someone else’s voice. And every time, I know whose voice it is—everybody’s, not mine. Each time I begin, someone else is speaking. Who is speaking now? Perhaps, it is I, since ghosts need no voice. Look at the light falling inside, the shape of elongated arches. Now, like an arch, it curves on the left. It will turn further and further and then disappear. Tomorrow again, from right to left, the slow dancing of shadows, like a pendulum outside time. So slow, sometimes observing these movements I fall in a daze, hypnotised for days. Then, I wake up like someone with prolonged sickness. In the absence of the children, I play with the sun. After the matriarch’s death, a feud began between the brothers. Who owns which column?

Whose room is under which Arch? They even divided the ground for the children, for my children. The farthest column belonged to the eldest son, the last to the third brother, and so on. It took a few days. The children were quiet, their symphony replaced by the howling and wailing of the other inhabitants. The mother, when she was alive, used to say, “How do you own shadows? How can anyone possess a house which is 300 years old? A house that has heard of 300 hundred deaths? Only the house can own the house.” When people leave, empty houses talk to other empty houses. When the other homes lose their voice, the solitary house talks to its rooms, its glasses, its gossamer, its lizards, its columns, its arches… Within a few years, all the brothers left along with their families. Barring the youngest (the fourth son), his wife, and his daughter. They stayed out of an attachment they couldn't define. Perhaps they couldn’t yet separate the deaths from the objects that were its witness —so many gone, leaving the high arches and the columns standing.

Then, the days of madness. On nights, when silence burst out like waves over waves and crashed into bodies, into souls, the last brother would come out with a hammer and smash the columns. He couldn’t reach the arches; he tried throwing the hammer thrice and failed. If you look closely, you’ll find wounds and gashes on my skin. The flower engravings over the borders are all deformed now—everything, a blessing from the hammer. After mauling, cursing, and thrashing, he would hold on to the columns, embrace them one by one, his hands almost meeting on the other side, and weep. Oh, what a loud lamenting it was! It is a bizarre thing with tears. They streamed down for a while, then seeped inside the block, the cement, and the rods. The wife consulted an astrologer, and they decided to leave was the only solution. On the last day, the daughter smiled, the wife wept, and the youngest son kept his eyes shut as if possessed. Perhaps, he is cured now. There are often unknown faces here these days—promoters, contractors, and different buyers. Touching us, measuring us, weighing us, painting us to cover the sores, the scars, the impressions time left on us. It was them again, I thought when I heard you for the first time. Stay awhile, stay till they tear us down, ground us to soot and smut. Witnesses to death want witnesses too. No, don’t stay. It’s a human thing. To be seen, to be remembered. We are only the bearers. We carry stories of others. And that is how we end, overflowing with fiction. Don’t stay… we avoid both humans and ghosts and the one’s living alike.

Ghost 1: Wherever we are, in search of other ghosts, we find things speaking. Where have all the ghosts gone? Perhaps, they have dissolved and become one with the objects they slept in. The things and the ghosts are one; things speak with the mouths of the ghosts.

We leave then. Once again, searching for things then, for when we die, some of us become things too.

(The writer is an assistant professor at the School of Language, KIIT in Bhubaneswar, and assistant editor, Journal of Posthumanism, Transnational Press, London)

Author note: I would like to acknowledge Anubha Fatehpuria (thespian and architect) for approaching me with the experimental concept of making architectural spaces speak. I also take this opportunity to thank Anirban Dutta (independent filmmaker) for generously sharing his magnificent photographs of old buildings and abandoned spaces of Calcutta.