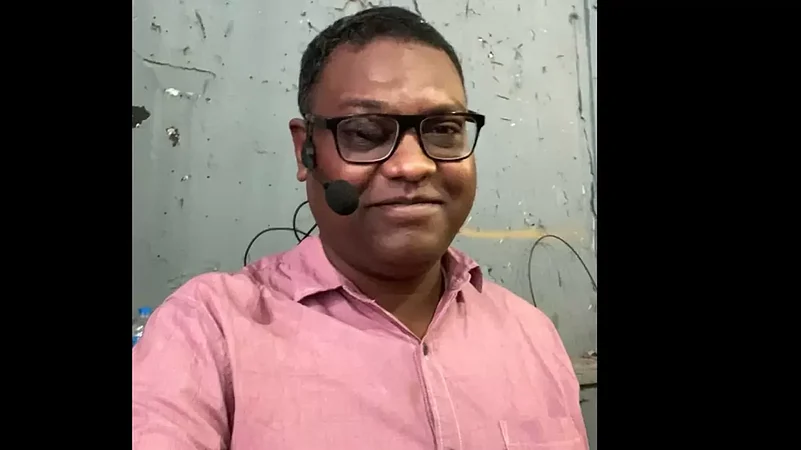

Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar is that rare being: an Adivasi writer from mainland India who writes in English. Most mainland Adivasis write in the dominant language of the state they inhabit (most Jharkhandi Adivasi writers, the state from which Shekhar is) write in Hindi.

The English publishing world in India, eager for new identity-based markets (not least because the English-speaking middle class has hardly anything worthwhile to say) has made Shekhar their darling mascot, as they do with various Dalit, Muslim, Kashmiri, gay and whatever other minority figures they can find.

Very often, these writers themselves are happy to be appropriated, for reasons ranging from economic gain to self-publicity and promotion. Others are simply not aware of the appropriation and do not move in the English-speaking world. Shekhar does and sits comfortably in this world. When I ask him whether as an Adivasi writer in English who has made his way to the English publishing world, did he feel boxed in an identity category there and whether he has been accused of selling out, he merely says, “I am grateful for all the opportunities that I found; am finding now; and, hopefully, will keep on finding in future.” It is a shockingly banal and evasive answer but Shekhar specialises in these.

Part of it is understandable. On 11 August 2017, the government of Jharkhand banned The Adivasi Will Not Dance, Shekhar’s first short story collection and arbitrarily suspended Shekhar from his job as a government doctor, on the grounds that the book portrayed Adivasi women and Santhal culture in a bad light. The key complainants included the ruling party in Jharkhand, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP); the opposition party, Jharkhand Mukti Morcha and several Adivasi writers and activists including Ivy Imogene Hansdak, Sunder Manoj Hembrom, Francis Xavier Soren, Santosh Besra, Shirijol Dingra, Alakjari Murmu, Innocent Soren, Tonol Murmu, Raj Kumar, Ashwini Kumar Pankaj, Gladson Dungdung among others. At that time, it was the English-speaking liberal intelligentsia who stood up in support of him.

The ban on The Adivasi Will Not Dance: Stories was removed in December 2017 and Shekhar's suspension was removed and he was reinstated into his job in 2018. But this has clearly left its mark on him. In his latest collection of short stories (though it might also be read as a three-part novel) My Father’s Garden, in the story ‘Father’, Shekhar offers a thinly veiled account of the actual contemporary political history of Jharkhand. When I asked him whether he was extra-careful about writing it given the offensive and intolerant attack on him, he said before its publication, “I was extra-careful, also anxious; but I wrote My Father’s Garden anyway.”

The quietly stubborn note in that ‘anyway’ is what redeems Shekhar from what one might otherwise read as political quietism. He may have changed the name of the BJP to HIP in it, the Hindu India Party, but the story remains a delicate, terrifying and ultimately tragic account of complicity, betrayal and ecological disaster.

The central component of what comprised the attack on him was on his descriptions of the sexual which were seen as demeaning to the Adivasi community. One the contrary, they might be seen as the most powerful aspect of Shekhar’s writing. From The Mysterious Ailment of Rupi Baskey, his first novel, onwards, Shekhar’s writing refreshingly, unabashedly and powerfully celebrates the erotic.

When I asked him about the role of the erotic in the aesthetico-political complex of writing, he said, “Aesthetico-political complex of writing” is quite a huge and intimidating term. I just find writing erotica pleasurable and sort of liberating.” Liberating it is. Shekhar’s visceral account of the protagonist’s homosexuality in the first story of My Father’s Garden entitled ‘Lover’ is unarguably the best writing in India on the particular, rancid, homophobic sex to which most Indian gay men are subjected by heterosexual-identified men.

None of his other erotic writing is disrespectful at all either. It is a joyful, fantastic expression of an embodied, occasionally liberated, female Adivasi sexuality, much needed when all we hear are accounts of rape and violence on Adivasi women by the paramilitary and military forces of the Indian state. In the bleak contexts of Adivasi lives, Shekhar’s writing gives us moments of celebration and sexual joy. Nor is it placed in a binary with danger, as sexuality often is. His writing calibrates equally the violence that often inheres at the heart of the sexual in a patriarchal world.

More recently, Shekhar has been writing for children and he has found that liberating too. “I find writing for children gratifying, especially when I see my writings accompanied by those wonderful illustrations. I am fortunate to have some amazingly talented artists draw pictures for my thoughts and words,” he says.

It is indeed tragic that rightwing forces and conservative forces from within their own communities misunderstand and attack Adivasi, Dalit and other minority writers. This happened to Tamil Dalit writer Bama too when she published her first book Karukku which was misread (actually, as with Shekhar’s case, not read at all, but misinformation was spread by community members) as denigrating the community. Bama was temporarily ex-communicated. As with Shekhar, hers was a nuanced account of complicity, patriarchy, violence and oppression. But minority writers are often held to be writing for the entire community and held responsible for absurd non-arguments about misrepresentation. A writer writes from her/his own vision and her mediation and understanding of the collective. No writing can please everyone. The primary pre-requisite surely is that people actually read it.

One only hopes people from Jharkhand will actually read Shekhar. His progressive politics are absolutely clear, evident in his most brilliant story, the eponymous ‘The Adivasi Will Not Dance’ which, he says, “was inspired by the laying of the foundation stone of a proposed thermal power plant in Godda district of Jharkhand in the year 2013.” Not that one has to be progressive to be left alone as a writer.

Thankfully for us, Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar continues his work as a doctor and as a writer. Asked what he is writing now, he says “Apart from translating from Bengali and Hindi, I am trying to write long-form.”