On October 2, a 130-year-old tiatr (Konkani language play) titled Cavelchi Sundari (The Belle of Cavel) created history after it was staged in Cavel, the tiny south Mumbai area that is the backdrop of the play. Over 250 locals walked up to the fifth floor of the Baretto School Hall (the lift was under repairs), to catch the 10 am show, which lasted for three hours. This was the first time the hall had ever staged a tiatr, notes Father Joe D’Souza, parish priest of Church of Our Lady of Health, Cavel. He had heard of play after the government-run Tiatr Academy of Goa (TAG) resurrected it in May to celebrate the 150th birth anniversary of its playwright João Agostinho, endearingly known as Pai Tiatrist (father of Konkani theatre).

Father D’Souza got in touch with tiatrist, publisher and acting coach, Michael Gracias, who had staged in the play in Goa, to stage the play in Mumbai. Gracias had taken two weeks to decipher the refined Bardezi or Church Konkani, smatterings of English, French, Portuguese, Latin and Hindustani in the script, and interspersed it with 12-14 songs (kantaram) in between the acts (pordhe) by Goa’s tiatrist legends—M Boyer, Jacinato Vaz, C Alvares, Ophelia, Alfred Rose, Rita Rose, Joe Rose, Miguel Rod, and others. “Many of the old timers loved the olden tunes and were singing along with the actors,” says Father D’Souza. More shows of play were staged at Kurla, Dadar, Matunga, and Kankavli in Mumbai. “For the Kurla show, we did nine out 11 songs encore on audience request,” reveals Gracias. Now, he says, the Kankavli organisers have requested him to stage Cavelchi Sundari as a musical, while Mangalore's St Aloysius College, he says, has expressed interest to bring the show to its premises, all expenses sponsored.

Cavelchi Sundari was Pai Tiatrist’s debut play, then called teatro in Portuguese, and later tiatr in keeping with Konkani phonetics. He, along with Goan emigrant Lucasinho Ribeiro, who had staged the first ever tiatr titled Italian Bhurgo in 1892, hoped that the Goan diaspora in Bombay would find their form of theatre to be a sophisticated alternative to the subpar forms of Konkani theatre that existed then. This meant zagor, in which actors were usually inebriated, mouthed profanities, and slipped in sexual innuendoes, neighbourhood gossip about extra-marital affairs, quarrels in between dialogues; and khell—travelling street plays that were equally crude. Pai Tiatrist wanted his scripts to educate the masses, rid of societal evils and stereotypes. According to the book titled, When the Curtains Rise—Understanding Goa's Vibrant Konkani Theatre, by Andre Rafael Fernandes, Pai Tiarist “was aware of the need to have his plays rooted in his own people and culture… he set out to explore the social problems and situations of Goa and Goans from the very beginning of his own efforts as a playwright when he composed The Belle of Cavel in 1893.” His first tiatr thus, became the exemplar for generations of Konkani tiatrists (playwrights, usually the director, writer and actor rolled-in-one) thereafter to script tiatrs that would hold a mirror to society, chronicling the good, bad and ugly.

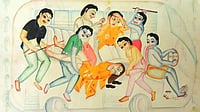

Take the case of Cavelchi Sundari, a tale scripted in 1890s Bombay under the British Raj. In it, two educated Catholic girls from the Goan diaspora want to ditch the arranged marriage route and marry for love. One girl leaves a suitor with a stable job for a wandering seafarer. The other takes a lover from a lower class, and continues the affair in a garden till her father discovers a love letter. Their fathers seek police intervention to separate the lovers, but the law sides with the girl. Scattered throughout the storyline are examples of emigrant Goans sidelining their Konkani mother tongue, but struggling to speak fluent Hindi. There’s a reference to the September 21, 1890, firing in Margao, Goa, which killed 23 Indians who were protesting against municipal polls rigged in favour of a Portuguese candidate. In one scene, unable to deal with the rampant casteism, the hero has an outburst from in Konkani: “...Coslem thond amim gheun bountat Christaum mun? Kitem munonam zait amcam Hindu anim Mussolman him. Castam polloun amche Christavam modem? (What face do we have to go around as Christians? What must not Hindus and Muslims be saying about us when they see these castes among us Christians?).”

Uncanny how the socio-political issues chronicled in the 130-year-old tiatr still find resonance today. Be it tradition vs modernity, women’s emancipation or even caste politics, over 90 per cent tiatrs are social dramas, “since tiatrs have been used as a very effective means of social reform,” notes Rafael in his book. A slow rise in anti-establishment themes began around the language agitation, when both Romi (Roman alphabets) and Devnagiri Konkani scripts fought for the inclusion of the Konkani language in the 8th schedule of the Constitution. Pramod Kale, in a 1986 article titled Essentialist and Epochalist Elements in Goan Popular Culture, says, “For tiatr audiences, Konkani is not merely a language, but a cause, a totemic symbol, a flag to rally around in fighting battles with the establishment and authority.”

Till the Goa Liberation of 1961, it was impossible to stage political tiatrs that mocked the colonisers. “Now tiatrists criticise the politicians sitting in the front row, and the politicians are left with no option but to laugh it off,” observes Rafael. Tiatrist Tomazinho Cardozo finds this unnecessary. “Some commercial tiatrs even criticise families of politicians. One section of the audience is already wary about this type of masala. When you hit below the belt, it’s not a nice feeling,” says Cardozo, ex-sarpanch, MLA and Goa Assembly speaker for one term and a school headmaster for 34 years. “Especially now tiatrists are taking the name of the politician they are mocking, which wasn’t the case earlier,” notes another tiatrist Peter Mendes.

“This could be the reason they don’t want us to perform,” observes Prince Jacob, monikered King of Comedy, hinting at why big auditoriums in Goa are either shut for repairs or in a deplorable state. The Kala Academy auditorium in Panaji has closed for renovation. Of the Ravindra Bhavans available for tiatrs, the Vasco hall is under repair for faulty air conditioning; the Margao hall is operational but has severe leakage issues in the toilets. The auditoriums in Ponda and Curchorem are not popular, and The Institute Braganza Menezes Hall does not have tiered seating, so the last rows struggle to see the stage. “Only hope is the makeshift open-air tiatr shows organised in churches and village squares with just curtains and chairs, without a fancy sound system or air conditioning. “Tiatrs are only surviving in Goa because of this minimal arrangement,” says Gracias. Much can be done to improve the living conditions of tiatr artistes, feels Jacob. “A government housing scheme can help veteran tiatr artistes living on rent secure a dignified life. Give production houses grants to buy a mini bus for on-tour travel. But the current government doesn’t care a damn about us. Whether you survive, perform or go to hell,” says Jacob.

A league of political kantaram singers like Francis de Tuem, Saby de Divar, Anil Pednekar and Olga Vaz, now have their own YouTube channels. Within a day or two of an unsavoury news report, these artistes upload a kantar, offering their viewpoint. Political kantarist and Trinamool Congress member Francis de Tuem, 47, for instance, launched his Modik Tallao song on his YouTube channel. “My song asked the PM why his photo was not published on the death certificate of the double vaccinated.” For his confrontational lyrics, however, Francis has had to bear the brunt. Once, ex-Nuvem MLA Mickky Pacheco sent at least 50 persons to disrupt his stage performance and even had him arrested under defamation charges. “Chor ko lajja mein nahi dalega, aur badega (If you don’t put the robber to shame, he will get stronger). No one has the guts to hold politicians accountable, but through my songs, they can,” says De Tuem.

The government’s apathy reached new heights in the pandemic. After much protest over the state’s inaction to extend financial help to the tiatr community after all entertainment venues shut down, a scheme was finally announced—Covid-19 Relief to the marginalised/unorganised sector. A one-time settlement of Rs 5,000 to cope with two years’ loss of income. Understandably, the community was enraged. “It was an election gimmick. Plus, it entailed tons of paperwork, like NOC, signatures from the collector, and travel for that paperwork in the lockdown. Many artistes did not take it,” says Jacob.

On the plus side

While the upper-class non-Konkani speaking crowd used to snub tiatr as an art form, calling it riff raff entertainment, productions like Cavelchi Sundari are changing that. Gracias’ formed Sant Matevachim Noketram (SMN) this year, a theatre group of young, well-educated professionals from Azossim, Tiswadi takula. It has Dr Shamin Pereira, a PhD in Library Science and is Assistant Professor in the Library and Information Science department at Goa University. Gracias noticed Pereira’s acting abilities at a tiatr workshop, and at 40, she debuted in Cavelchi Sundari, playing the friend who helps the protagonist carry on her clandestine affair. In Polio Gontt (First Sip), another Gracias play, she plays a ‘doubting Thomas’, pushing her husband and son to the brink. “My nieces 16 and 11 old, on seeing me act, have joined the Poilo Gontt production to sing a few songs. I will keep acting in tiatrs because now I am confident as an actor.”

Gracias has conducted over 150 tiatr workshops for youth in mainly remote parts of Goa. His SMN group of young actors won the prestigious Mando of the Year award at the 54th Mando festival this year, along with 13 TAG Group B awards. His organisation Kala Niketan annually felicitates deserving tiatrists with ‘Tiatr Ratna’, ‘Tiatr Bhushan’ and ‘Tiatr Vibhushan’ awards. Pai Tiatrist, Gracias documents plays by publishing the scripts for posterity.

Gracias’ tiatrs are helmed on family, social themes with a political edge. His Nachchona Kumpasar (I Will Not Dance to Your Tune)—borrowing from veteran crooner Lorna Cordeira’s song Nachom-ia Kumpasa—dwells on tactics politicians employ to fool the youth. Sintidan Pai Ghal Go Bai (Walk Cautiously Baby) was a reaction to the Nirbhaya rape case in Delhi and the rape of a 12-year-old girl at a school in Vasco, Goa. “I aim to ‘conscientise’ people. Discussing these happenings in taverns does not make you a responsible citizen. In Sintidan Pai… after the trial court finds the rapists guilty, their lawyer tells the victim, ‘See you in high court’. This is delayed justice. This is reality.”

Bai Regina, who from age eight till now 80 has essayed all kinds of roles, and who in the early day had to put up with “people who would gossip behind my back for being a women actor rehearsing till late night”, is now enjoying the fruits of her hard work. The Rs 1,200 monthly pension she received on turning 60 was raised to Rs 2,500, and finally Rs 3,200 in 2019 after she won the Rs 1 lakh state award for acting. “So, I cannot say the government has not done anything for me.”