Aamra je jyotsna ke eto bhalobasi – ei garho roopkatha

chand nije janey na tow

(Moon has no knowledge of the deep fairytale of our love for moonlight)

The moon is said to have turned many people lunatic over centuries, without having an iota of idea of her own charm and influences. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak served as the moon for poet Binoy Majumdar in Calcutta of the early 1960s, resulting in a series of poems that would launch him as one of the most important poets in post-Independence Bengali literature.

“Sokol phuler kachhe eto mohomoy money jaoar poreo/ Manush kintu mangshorondhonkaleen ghraan sobcheye beshi bhalobasey (Even after being bewitched by flowers, man still loves the aroma of meat being cooked, the best),” he wrote in one of the poems, and in another, “Manush nikotey ele prokrito saros urey jay (Real storks take flight at the approach of man).”

The lines quoted above are from Phirey Eso, Chaka (Come back, O wheel), his book of 77 poems published in September 1962. It was dedicated to Gayatri Chakravorty. Soon, this book became a sensation, even if mostly among people having an advanced literary interest - poets, writers, critics and academics. Poet-novelist Malay Roy Choudhury later compared the publication of the book with the ‘Cambrian explosion’ in Bengali literature. Poet-novelist Joy Goswami described him as a man ravaged by his dreams.

Jenechhi nikotoborti ebong ujjwolotomo taraguli prokrito prostabe/

sob groho, tara noy, taap-heen, alo-heen groho.

(I have learnt that our closest and brightest stars are nothing but planets, not stars, heatless lightless planets).

His poetry has remained widely discussed and analysed over the next six decades, not only in West Bengal but also in Bangladesh. In fact, one of the most comprehensive collections of his poetry, essays, interviews and writings on him have been published from Bangladesh. Some of his poems have been described to be bordering on eroticism, while some others as outrightly erotic. Some have called his poems ‘serene mathematical beauty’ for his experiments of blending poetry with mathematics; that is, seeking to solve mathematical questions through poetry, seeing them as reflecting the same eternal truths.

But it is probably his one-sided and failed love, or rather obsession, for Gayatri that has taken up the lion’s share of the talks regarding him. Perhaps, because this obsession gave birth to poetry collections full of quotable quotes.

Bhalobasa ditey pari, tomra ki grohone sokshom?

Leelamoyee koroputey tomader sob-e jhorey jay -

Hasi, jyotsna, byatha, smriti, oboshishto kichhui thake na.

(I can offer my love, (but) will you be able to receive it?

Everything spills out of your playful palms –

Smiles, moonlight, pain, memories, nothing stays.)

or,

Tobu sob brikkho ar pushpokunjo je jar bhumite durey-durey

Chirokal theke bhabe miloner shwasrodhi kotha

(And yet all the trees and flowering shrubs standing apart from each other,

rooted to their own soil, keep breathlessly thinking of their union)

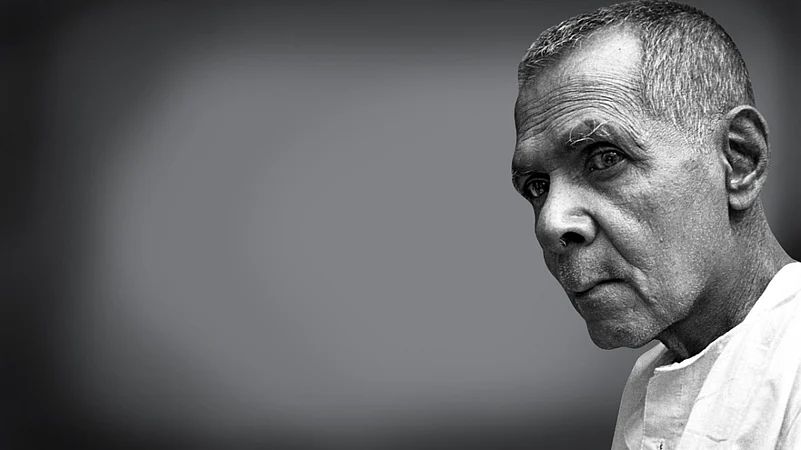

Frequently described as a mad genius, Majumdar was born in present-day Myanmar in 1934 and brought up in Faridpur (Bangladesh) and Calcutta in a lower-middle-class family. He passed his graduation in mechanical engineering from the BE college in Shibpur in 1957, standing first class first, and his first book of poems, Nakshatrer Aloy (In the light of the stars), was published in 1958. He became closely associated with the members of the Krittibas group of poets and writers, who were the talking point of Bengali poetry in the 1950s.

During 1958-61, he worked briefly at the All India Institute of Hygiene and Public Health, then as a development engineer at the Indian Statistical Institute, Calcutta, and taught at the Government Engineering College in Tripura, before taking up a full-time job at the Durgapur Steel Plant. He even got an offer from an institute in Berlin to teach mathematics but let it go after his parents objected to his going abroad. He also translated five books on science and general knowledge from Russian and a book on the theory of relativity from English.

Then, to the shock and dismay of his parents and brothers, he decided to quit his fourth job to pursue poetry full time.

As the narrative appears from the accounts of Majumdar’s friends and contemporaries, including Shakti Chattopadhyay, Sunil Gangopadhyay, Sandipan Chattopadhyay and Malay Roy Choudhury, among others, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, now a globally known postcolonial theorist, was studying at the Presidency College for her bachelor’s in English during 1960-61 when Majumdar caught a few glimpses of her. She was a friend of some of his friends.

Though the accounts are not exactly clear, they possibly never exchanged any words between them. Perhaps, Majumdar’s fear of rejection prevented him from initiating any conversation with her. But his correspondences with Shakti Chattopadhyay reveal that he was desperately looking for Chakraborty’s postal address and was asking many of his friends for it. He even traced one of her relatives and wrote to him but he advised him to stay away from her.

His obsession with her resulted in his second book of poems, a thin collection of only 14 poems, titled Gayatri-ke (To Gayatri), published in March 1961. It was dedicated to “Amar Ishwari”, meaning my goddess. The next year, he expanded it into the 77-poem book, Phirey Eso, Chaka.

However, it was in 1961, in the time between the publication of Gayatri-ke and Phirey Eso, Chaka, that he had to be hospitalised for six months due to mental health issues. By that time, Chakravorty had left for the US for further studies.

Ishwari, nevertheless, continued to dominate his writings. He published a third version of the book in June 1964, with 79 poems, and named it Amar Ishwari-ke (To my goddess). In the introduction he added in this version, Majumdar expressed his hopes that even though the poems dealt particularly with his pangs, they had a universal appeal. “From my perspective, this book of poems is all about the pain of love,” he wrote, “Centred on a female friend, this set of poems only about the pain of love is an appropriate diary.”

Three months later, he published another book of poems, titled Ishwari-r (The Goddess’), in September 1964. It included all the poems contained in Ishwari-ke, the next year, he published Ishwari-r Kobitaboli (Poems of the Goddess).

Much later, he wrote to Tarun Bandyopadhay, who edited Majumdar’s poetry anthology in 1993, about naming his second book as Gayatri-ke: “Gayatri Chakraborty studied in Presidency College. She passed the B.A. as first-class first from Calcutta University in 1960 or 1961. I wrote the book Gayatri-ke, addressing her, with the understanding that only she will understand my poems.”

During 1963-1964, he also got associated with the writers of the Hungry Generation, the second major literary movement in post-Independence Bengali literature after the Krittibas movement. However, he was not an active part of either group.

Since the 1960s, he has been in and out of mental hospitals innumerable times. Majumdar left Kolkata in 1967 and returned to live with his parents at Thakurnagar, close to India’s border with Bangladesh. Around his time, he even walked past the Indian border, went to Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) and, according to his interview to Jogsutra magazine in 1993, he had voluntarily surrendered before the police there and pleaded with them not to send him back to India. He was expatriated after six months in jail, following which he lived in Thakurnagar.

He became a recluse. He never took up a job. He neither married nor engaged in any romantic relationship. He lived with his parents till their death in the 1980s and alone thereafter till his death in 2006. He often stopped writing, for months, even years. But editors of various literary publications from different parts of Bengal continued to coax him to write. His 1974 poetry collection, Awghraner Onubhutimala (Feelings in November) became another book of legendary status.

In the last 10-12 years of his life, the state government paid him a monthly pension and some Kolkata-based writers and poets made an arrangement with the residents of Majumdar’s neighbourhood to look after him. He was awarded the West Bengal’s government’s highest literary award, Rabindra Smriti Purashkar, and the Sahitya Akademi Award, both in 2005.

Nevertheless, it appears that Gayatri remained his eternal muse. As late as 2003, he wrote a poem, titled “Aamra Dujoney Miley Jitey Gechhi Bohudin Holo,” which critics considered was about none other than Chakravorty. Translated to English, it reads:

We two have

We two have won a long time ago

Your complexion remains unchanged, yet faith has changed to Christianity from Hinduism.

You and I have aged

I saw in photographs published in daily newspapers that you have

cut your hair short

Like me; Did we know we’ll grow old

when we were young?

I hope you have children and grandchildren now,

You have my address

And I have yours

We will not write letters to each other.

We live together in the pages of the book.