A narrow, dark corridor on the second floor of a commercial building in the Barbarshah locality, about three kms from Lal Chowk in Srinagar, leads to the small, one-room office of Sonzal Welfare Trust. There is no board outside, but inside, there are posters showcasing the work done by the Trust—which was set up in 2017 to build a supportive institutional framework for transgenders in the Valley so that they can lead a life of dignity, access proper sexual and mental health care services and sustain themselves.

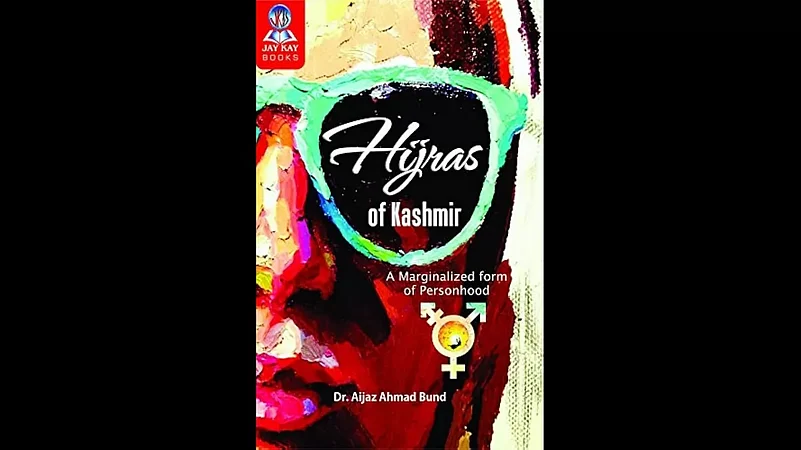

Aijaz Ahmad Bund, the anchor of the trust, and the author Hijras of Kashmir: A Marginalized Form of Personhood, a pioneering ethnographic exploration into the transgender community of the Valley, begins his conversation with a request.

“You may be aware of the various interviews I have given about my life and my work about the transgender community. It has been quite a journey. What I’ve noticed is the persistent misrepresentation with misgendering. It’s deeply hurtful,” says Bund, a man with a mild demeanor, who sports a flowing beard.

“What I often feel is that those who talk to us tend to reduce our identity to sexuality. Yes, I identify myself as a queer person, but my identity is also much more. I am a son, a loving father, and I am an Assistant Professor, and I take part in various other pursuits,” he says.

After a pause, he starts talking about the struggle of the transgender community in a region like Kashmir, his work, and his life. “The struggle for our existence is a hard one. No one can imagine it. It is everyday oppression, and we live with it. The forms of these oppressions are different, but we live under the weight of these oppressions,” he says.

He cites his example, saying: “Consider my case; I hold a degree, a Ph.D, and yet, I face consistent harassment. The trigger is often when people come to know about my identity and my work.”

While Bund says there is a perception that the transgender community is respected in Kashmir, it is just a perception. He says Reshma’s case is an exceptional one and it cannot be generalised. In November last year, the entire Valley grieved when Reshma—the voice of the transgender community in the Valley—died. Hundreds of people participated in her last rites. Her song ‘Haye Haye Wasiey’ has over five million views on YouTube.

Contrary to the claims that mosques are welcoming grounds for transgender individuals, Dr Bund says that the situation is quite different. “I entered a mosque recently to offer prayers. One person who might have heard about my work got triggered and started shouting at me and asked me to leave. He said that I had made the mosque profane and had desecrated the sanctity of the place by entering. I refused to leave. I offered prayers, but the incident shook me, and I couldn't get over it for days," he says.

Bund, whose Ph.D thesis was on the lives of ex-militants who had surrendered, blends seamlessly into the crowd, but incidents like what happened at the mosque, are an indication that life goes by a thread. As a cisgender man, Dr Bund moves around freely until he is recognised, and when that happens, he is confronted and harassed. “Imagine those who have crossed the boundaries of conventional norms? As I walk the streets, silence prevails. I pass as a cisgender man, but what about those who do not? The degree of societal harassment hinges on visibility and invisibility.”

While Reshma was given glowing tributes on social media, Dr Bund says other transgender persons are not so lucky. Bund, who has been deeply involved with the community since 2010, says their lives are marked by adversity from childhood until their death. “Many actors determine their marginalisation, like the place of birth and the families they come from. Those from rural areas face more marginalisation. Bullying begins early in their life, often at home when they don't conform to cisgender norms. It starts at home and continues in schools, often manifesting as physical abuse. And the result is in Kashmir, we witness a 99.9 per cent dropout rate within this community. The answer lies in this relentless bullying in schools.

“Once they are out of school, they are left with the only choice of a profession that is matchmaking and at times dancing at marriages,” Bund says. He says once they step out of their families after being abandoned by them, their traumatic experience begins. “At home, their very existence is seen as a disgrace; they say their very existence stains the family’s honour, and subsequently, society treats them in a manner that makes violence, abuse, and discrimination normalised for them.”

The transgender community encompasses two primary identities—male to female and female to male. And it is the female-to-male transgender identity that frequently battles acute gender dysphoria, and their quest for shelter forces them to leave their homes from rural to urban expanses in search of invisibility. And it is the marginalised communities, such as the sweepers or Hanjis, where they find shelter. It is traumatic for them to even name their families or revisit their homes. Their love is seen as an act of lust, and once abandoned, they are abandoned for life, and once they die, no one claims them.

In 2018, Bund received a distressing call from the community—a 23-year-old transgender community member from southern Kashmir had died in rented lodgings due to brain haemorrhage. The police insisted that his family should claim the body. He had left his home over a decade ago, and the family had severed all contact with him. “I contacted his family. They told me that he had brought disgrace to them while alive, and now he continued to do so in death. I was frozen. Later, I requested his sister to claim his body. She accepted after several pleadings but laid a condition that no one from the transgender community should visit his graveyard or the village. We agreed. And for four days, we mourned his death in Srinagar.”

“Despite a lifelong companionship with him, we were denied the right to grieve by society, even in death. We were not given the right to mourn,” Bund adds.

On another occasion, Bund says an elderly transgender person afflicted by Alzheimer's disease was lying outside the UNO office in Srinagar, and they moved him to the hospital. Dr Bund says after his discharge from the hospital, he brought him to the office and started searching for his address. He found it in the Bandipora district. After Bund traced his home and informed his brother to take the person back, he refused, saying they did not want to bring impurity to their homes. “I never get angry, but at that moment I shouted,” he says.

The transgender community no longer works on Fridays, reveals Bund. He says due to the relentless harassment faced by transgender individuals after offering prayers, the community decided not to turn Friday into an off day. The religious beliefs and religious orientation of the transgender community are challenged by society. “A transgender individual Reshma had the courage to recite religious texts at a wedding, only to become the target of persecution. She was forced to apologise,” he adds.

Bund’s own journey of engagement with the transgender community began during his student days at the University of Kashmir. “While pursuing my master's degree in social work, I confided in a colleague about my intention to work with this community. He responded with laughter and concern, saying, ‘What will the world say?’ I talked about working on the transgender community in class, only to be met with laughter.”

Bund had concealed his queer identity for a long time. While not proclaiming his belonging to the community, he aligned himself as an ally, yet he was subjected to ridicule and harassment. This motivated him to work with the community as an obligation.

He recalls that a transgender individual once sought entry to his home for matchmaking for his elder sister. His entry to the house was resisted by Bund’s mother. He requested his mother to allow the guest in. Once inside the house, the mother refused to serve him tea. But Bund didn’t relent. He beseeched his mother to prepare tea for him. “Later, my mother refrained from touching the cup. She perceived it has been now tainted after being touched by the transgender person,” Bund says. This incident left an indelible mark on his consciousness. He left science subjects and started pursuing further studies in social work only to work for the community.

When Bund embarked on this journey in 2010, when no one was talking about the transgender community, death threats were common and a fierce Twitter campaign was initiated against him. “I was labeled as an infidel, even referred to as a blot, who should be exterminated. I was called apostate. What hurt me most was that they abused my family, least they know about my family,” he says.

Bund, as a social media experiment, started examining some accounts that were threatening him citing the religion. On examination, he found that many of them were living liberal lives for themselves, posting obscene pictures, but for the transgender community, they had strong religious beliefs, and a queer person's existence was seen as a threat to the religion.

The threats, however, had been deeply traumatic for Bund.

“You don’t know what a person walking next to you is up to. You live by a thread.” He says many transgender people are deeply religious. “Often faith and sexuality are seen as an oxymoron, as antithetical to each other, especially when it is alternate sexuality,” he says. But he has seen many transgender people being very argumentative in favour of the religion and reading the Quran. “Since they don’t get space in the mosques, they are often seen in shrines,” he says.

The only intervention in the community from the political side has been former Finance Minister Haseeb Drabu’s initiative to empower them. Bund says in his budget document and speech, he had talked about the community. He says Drabu was interested to know what could be done for the community. “Once he was out of the government, nothing happened,” Bund says.

He says the conflict situation in Kashmir has overshadowed many other issues, including the problems of the transgender community. Despite his research and association with the community, he says he is not an expert on the community. “As a researcher, I want to say they are the only experts on their lives.”

He says more than ordinary people it is educated people who have complete disregard for the existence of the third gender.

A documentary, ‘Trans Kashmir’, was screened at the University of Kashmir recently. “I felt that walking in the University of Kashmir campus after the screening of the documentary was my longest walk ever. That day it seemed to me my walk would never end. Everyone was looking at me, rather they were looking down at me. It was supposedly the educational class’s reaction to the film and me. I have been assaulted in Lal Chowk, and I have seen the worst kind of atrocities inflicted on me, but I was never as uncomfortable as I was that day in the University. This is exactly what our lives are,” he says and takes a deep sigh.