Journalist Shirish Khare collected an account of the persecution and turmoil of approximately a dozen places from various states while travelling through all the difficult roads in the book 'Ek Desh Barah Duniya,' recently published by Rajpal & Sons, New Delhi. Shirish Khare's book is a compilation of articles based on his travels to these places, and it disproves the government's claims of improvement. This book provides a perspective on India that does not make the front pages of any newspaper or become breaking news on television. Due to a shortage of space in local newspapers, such events are usually forgotten.

Shirish refers to his experiences as a journalist as 'Ek Desh Barah Duniya,' emphasizing that a single country contains twelve separate universes. In reality, tucked away in the margins of this book is a glimpse of actual India. This book has been awarded the KLF Book Award for 2020-21.

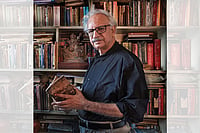

The book's author, Shirish Khare, speaks with Ashutosh Kumar Thakur.

The name 'Ek Desh Barah Duniya' is intriguing, but what does this strange non-fiction book contain?

Different regions of a country may appear to be the same, but the local context is taken into account when we spend a few days in an intimidating, challenging location and add modest emotional stories from the many real individuals who live there. We write about current events with this in mind, and despite the fact that we are writing about the same subject, the world there looks to us to be extremely different from the rest of the country. For example, when we talk about the Korku tribes' food situation. When we write about the food issue among the Korku tribes at the hill of Melghat in Vidarbha, we try to get to the source of the problem, which is similar to Mumbai's hunger. We feel that when the tribes' lives were cut off from the forest, their world shattered from Melghat to Mumbai.

You discussed Melghat and wrote extensively on the new challenges that were arising on the Narmada's banks as a journalist travelling along the river's banks. Was it realistic for you to write a whole book about one location rather than twelve different places?

Despite the fact that there are twelve separate planets, I believe there are stories about one continent. When you look at any one issue from multiple perspectives by travelling to other locations, you may get a better image of actual India on a bigger scale. Let me illustrate with an example. There may not be any repeat on the route from Melghat, the first world, to Achoti village in Chhattisgarh, the outer world. Even yet, certain strands, such as Melghat, go through each stop from beginning to end. Drought symptoms can range from brief to lengthy. Despite not being one, the worlds of two entirely distinct societies, one forest and the other agro-based, appear to be linked here by symptoms of drought or something like.

You intended to create a fictional universe in Kamathipura, Mumbai's red light district. What are your thoughts on the space you used in your book?

About 10 years ago, I published a report called "Life Waiting for the Greenlight" from there. While I was writing it, I had the notion that the sights I was witnessing, the facts I was accumulating, and the things that were occurring to me should be taken out of the report and published as fiction or nonfiction, since they may be more significant than the material in it. That's why, in this and previous reports, I attempted to write in a literary manner in terms of language and presentation, but I'm primarily a journalist, so I tried to give the truth about the events by preserving the facts and details as they are.

Have you had any reaction to attempting to tell Kamathipura in person?

This endeavour shattered a lot of my mindsets. These details may be found in the book. In fact, I conducted numerous informal interviews with them in order to have a better understanding of the life of sex workers at the time. Then I realised that whatever I had been thinking before was no longer there. Many topics may still be fresh in my mind after authoring the book, so I'm approaching it as a learning experience. If someone tells me I'm not doing anything right here, I'll attempt to learn from him there, and if I'm doing something correctly, I'll strive to better myself, since the streets of Kamathipura have taught me that I may be proven wrong at any time.

Is there someone whose comments have gotten into your head and caused you to think about yourself?

Many people recall the storey in which Bhura Gaikwad of Tirmali Basti in Kanadi Budruk village in Maharashtra states that a home circles in everyone's head to return, but no one returns to the nomadic Jamaat's mind. The home is immobile. After listening to him, a house appeared in my thoughts for a long time, and I began to believe that coming home after completing a journey provides the same sense of relaxation as finishing a book, but when I return from travels, I frequently travel to new cities. When you return to various residences in Bhopal, Mumbai, Delhi, Jaipur, Barwani, and Pune, the addresses of the houses change. Finally, I recall the house in Madanpur, which serves as my permanent address.

After a lengthy battle inside mainstream society, the Tirmali Jamaat of Kanadi Budruk hamlet finally finds its address, according to your report. Is this enough of a change?

Those frightened of the police are hesitant to board the buses. Even if the struggle of individuals from the same group results in an inspector in the next generation, or if a female becomes a conductor on a state transportation bus, the outside community may receive a first look. This alteration was unnoticed by me. Consider their battle, in which their elders were continually chased out and were not permitted to stay in their community for lengthy periods of time. On the other side, while the Sayyid Madaris of Maharashtra's Ashti town have the address, the younger generation of this group, who play Madari on the streets, has become a target of conflict. The Pardhi children of Mahadev Basti are in a similar situation. While reading these accounts, you might question if the changes going place in those locations signal a new threat.

In the report "Sugar is bitter in sugarcane fields," you notify the farm labourer trapped in the trap, despite the exploited crop, but you don't give a choice. The new thing may be suitable in its place, but repetition is necessary when expressing oneself becomes more difficult than before.

When I was preparing the press release in Raipur, there was a person I never met, but I spoke with him and composed a small poetry at the time. Meena Khalko was a lady who was allegedly killed by police officers. He was allegedly murdered in a police confrontation. Many questions surfaced afterwards, after his death. Then, while working for the newspaper, I had the opportunity to spend some time in Jagdalpur, Bastar district, and visit several neighbouring sites. Many news articles should have been on the top page, but they were jammed into double or triple columns when I examined old newspaper files during editorial support at the newspaper's office. This indicates that the news, which had grown significant outside of Bastar, remained unimportant in Bastar. For example, more than two dozen families in Abujhmad trek for six nights on the road to obtain rations, but when they arrive in Jagdalpur on the seventh day, the employee refuses to give them a ration, alleging a technical reason. Following that, I performed reporting on issues such as schooling from Jagdalpur's surrounding areas, as well as visiting marketplaces and other locations. As a result, you might consider the novelty I felt as an outsider.

(Ashutosh Kumar Thakur is Bangalore-based management consultant, curator, and co-director of the Kalinga Literary Festival.)