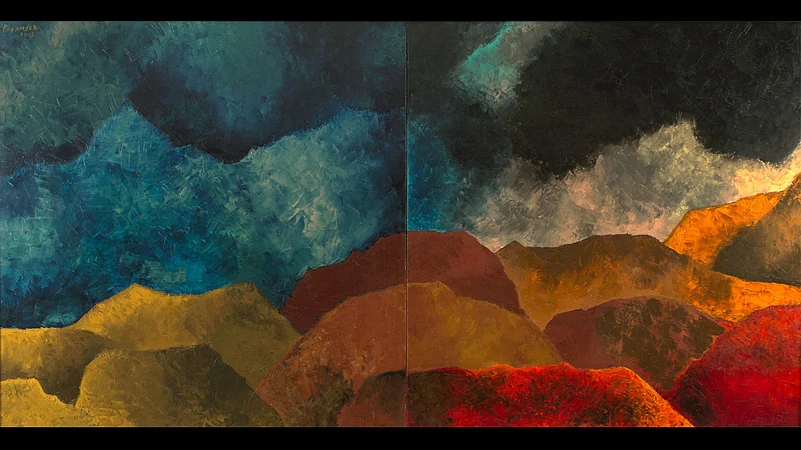

A cosmos of hills and ravines simmers in its stillness. A river cuts through the landscape in that arrogant way only rivers can. In the distance, a lake, lush with life and an unseen moon’s quiet shimmer. Each element, each miscreant framed by an eastern sky of silent splendour. On a 120x182 cm canvas, a mélange of life, dream, and that strange, surreal somewhereness in between.

I first chanced upon Akbar Padamsee’s ‘Metascape ’74’ in a book about the artist, sometime in my early twenties. What struck me immediately was the sense that the address his brush and his imaginations had shaped was somehow known to me — a landscape of disquieting beauty and arresting endlessness. Had I encountered it in a journey, chanced upon it in a photograph? Did the portrayal belong to a faraway reverie?

The art’s potency has revealed itself to me again only now, over fifteen years have passed, given the sense of remoteness that has gripped our lives over the past couple of years, brought about by a global pandemic and its recurring tribulations.

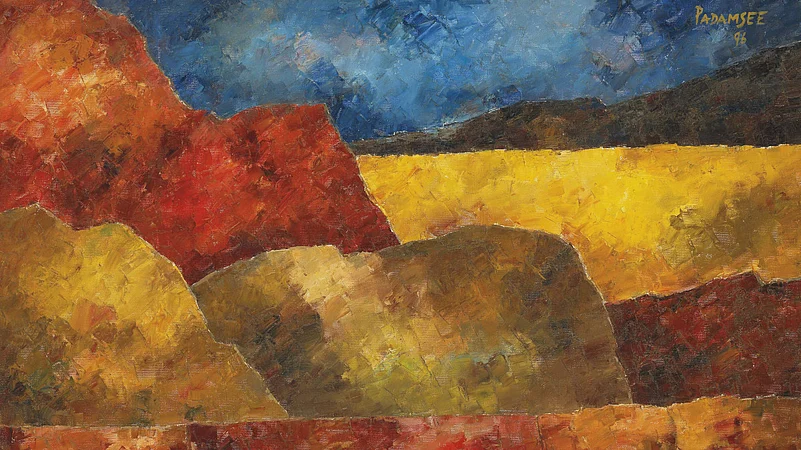

The Metascape had, of course, been a lifelong love affair for the artist, these “metaphysical landscapes” first coming to life during the 1970s, prospering intermittently over the decades. In these vast canvasses, Padamsee was free to explore some of his greatest obsessions — his fidelity to a certain mathematical exactness; a sense of playfulness amidst his intellectual wanderings; interrogations of the metaphysical world; the brilliance and interplay of colour; an abiding interest in Sanskrit manuscripts (especially Kalidasa’s ‘Abhijnanashakuntalam’, which introduced him to the concept of the sun and moon as overseers of time).

What Padamsee’s Metascape Series also allowed him to do was play with form. Some of these canvasses are vertical; many stretch out horizontally. Some are mirror images where each image remains incomplete without the other, each not simply an inversion but also an interpretation of the other, allowing Padamsee to revel in his investigations of duality and otherness, giving him enough space to flood colour, replication, and iteration into his work of juxtaposition Then there are the diptychs that don’t mirror images — two-image landscapes of breadth and vastness, lost in the abyss of the artist’s private mindscape.

I return to ‘Metascape ’74’ often. Often, it stares back at me. The work’s gathering of umber, burnt orange, dark browns, light blues, and an almost colourless glisten might have appeared morose in a lesser artist’s hands. But given Padamsee’s astonishing deftness with colour, it almost becomes a paean for hope.

Padamsee’s mastery over colour is part of Indian artistic folklore. His initial grounding in colour’s vagaries was at the JJ School of Art, Bombay. But it was in Paris that he was introduced to Paul Klee and the first volume of his notebooks — ‘The Thinking Eye’ — which further familiarised him with Klee’s Bauhaus lecture materials. One particular section — the one on colour, with its central obsession being Goethe’s colour theory — consumed him entirely, instigating a lifelong love affair with the study and manifestation of hues.

Really, it’s colour — informed by an intellectual awareness; fed through the prism of a near-mathematical thoroughness — that has cemented Padamsee’s place as the bastion of conceptual contemplation, forever preserving his place in the pantheon of Modern Indian Greats. From those early days in Bombay and an induction into the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group (where Souza, Raza, Husain, Mehta, and he, with chosen others, would script one of Indian art’s most compelling narratives), to moving with Raza to Paris in the late 1950s, Padamsee’s was a journey of perpetual cerebral discovery.

Within the Metascape Series, I tend to wander like a pilgrim. The paintings are rarely if ever, titled. I rarely mind. The other work that has had my heart for years now is the Metascape from 1975. In this, howling, intoxicating blues and an almost alligator-like shoreline are crested by a crescent moon aglow in its perfections, while to the distant right, a yet-asleep sun awaits its place in the firmament.

And yet it’s ‘Metascape ’74’ I keep returning to, like a lover drunk on old memories. Right through our recent and current seasons of isolation, it has proven to be a confidante — listening, sans judgment; offering the fierce counterpoint of beauty. Most startlingly though, it has served as a mirror-image to the here and now — the painting and life in the present being reflections and reiterations of each other, each incomplete without the other — art and the world thus becoming the fused diptych that Padamsee devoted so much of his life to.

In a remarkably prescient manner, the work — in fact, the Metascape Series as a whole — has foreshadowed our current malaise, while offering us a way out of it. Each segment forms part of a larger, geometric something. Lines carefully map their trajectories and destinies within the lattice-like cosmos of the world. Patterns and possibilities evolve towards certain human poetry. And from this, an answer is born.

I stare deeper into the heart of ‘Metascape ’74’. As it always has, the painting stares back at me. Padamsee passed away in 2020, but his voice and his gaze remain eternal through his art, as does his legacy of wisdom, beauty, and a certain existential philosophy. Through ‘Metascape ’74’, he seems to be telling me: “Look, I know there is darkness and the night seems to be a cauldron of shadowy rivers and shrouded valleys. But look again — the lake’s bristling sparkle, the unseen moon’s triumphant existence. And look again to the east — that emergence of light, and with it, hope.”

We’ve learnt to swim in the textures of the darkness. We’ve learnt to hold on to the light. And somewhere, Padamsee is smiling at our acceptance of this most fundamental of human diptychs.

(Siddharth Dasgupta writes poetry and fiction from lost hometowns and cafés dappled in the early morning light. His fourth book, A Moveable East, was published by Red River in 2021)