On a chilly winter evening, Mohd Ramzaan opens the half-clinging patched door of his rented single-story house in Zaina kadal area of Shehr I Khaas, his shoulders decked with an unbearable load of half-done kani shawls. He made his way through a narrow lane towards his master’s place, with a ray of hope that his master might reward him for his work today. Ramzaan had made several rounds of his master's house in Aali Kadal so he could pay his daughter's fees on time, but all had gone in vain.

His master, Farooq Ahmed, kept him waiting for his payments for weeks—or rather, months—together. He reluctantly asks him to sit along and quickly wants to hear his plight, already knowing the reason for the visit. Ramzaan very politely showcases his beautiful shawls, which were under process, and very hesitantly asks for his well-deserving reward.

This time, the master decides to set him free and finally hands over just a note of 200 rupees as a tip to get rid of him. Ramzaan’s hands started to shake, and his eyes were full of tears. He had spent sleepless nights filling the beautiful Badam motifs with pleasant colours as if they had just bloomed.

But alas! His master didn’t show pity. He didn’t care; he just wanted to achieve his target of exporting antique jamavars to the U.S.A. for a business ceremony, which Ramzaan’s hard work had helped him achieve. Mohd Ramzaan, highly dejected and disappointed, returns to his home and turns on his radio to divert his disturbed mind. Listening to Rasul Mir’s energetic kalaam, he feels a bit better and decides to start completing the left-over work. After all, it was his ancestor’s gift, so he could never even think about something else.

Countless more, like Mohd Ramzaan, strive to meet both ends.

From the delicate artistry of shawl weaving to the intricate carvings on walnut wood, the city’s artisans have been breathing life into stunning creations for generations. Srinagar, the heart of Kashmir, is the proud fourth member to secure a coveted designation as a world craft city by the World Craft Council. This prestigious recognition places Srinagar among the elite league of Indian cities celebrated for their rich craft heritage and thriving artisan communities. Srinagar joins Jaipur, Malappuram, and Mysore as the fourth Indian city to receive this honour. The recognition comes three years after Srinagar’s inclusion in the UNESCO creative city network for crafts and folk arts. Beyond the snow-capped Himalayan Mountains and serene lakes, Kashmir’s looms witness century-old tradition and craftsmanship. Kashmiri weaving involves intricate patterns and techniques that echo the stories of generations that have dedicated themselves to preserving their heritage.

Kani shawls, being one such testament to exquisite craftsmanship, reign as supreme artistic creations in the rich cultural heritage of Kashmir’s weaving traditions. Known for its elegant designs and luxurious finishing, a Kani shawl is considered a prized possession across the globe. Every Kani shawl design is a living history where quality and artistic excellence converge beautifully.

The origin of the Kani shawl is a quaint village named Kanihama, nestled in the lush green valley of Kashmir. Kanihama itself means ‘Kani,’ which refers to wooden sticks, and 'Hama,' which means village. Artisans use a small wooden stick called ‘Kani’ and wind colourful weft threads around these sticks to create intricate patterns on the shawls. That is why it’s also called tuje pashmina (tuj meaning sticks). These wooden spools or sticks are made from forest wood, known as ‘poos tul.’ Although initially, Kanihama held a monopoly over the production of Kani shawls, artisans from neighbouring villages acquired the skill of crafting these exquisite shawls over time.

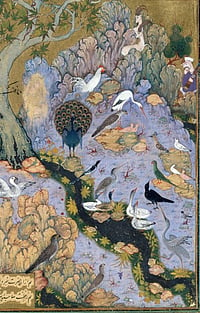

According to historians, the art of Kani shawl weaving in Kashmir has Persian roots. During the Mughal era, particularly under the rule of sultan Zain ul Abideen (Budshah), the valley had more than 15,000 functional Kani looms. This historical period marked the most celebrated era for Kani weaving, ultimately paving the way for it to become an art form. Quoting Mohibul Hassan, with reference to his book “Kashmir under the Sultans",

"During the sultanate period, other than salt, shawl wool was the most important thing to be imported. From the Mughal accounts, it was known that the shawls were exported to all parts of the world, and there were thousands of shawl factories; however, the exact number cannot be drawn from the chronicles, but it is said that during the era of King Akbar, 2000 shawl factories existed. Most importantly, the taxation system was highly rigid during this period.”

After the Mughals, the Afghans left no stone unturned in extracting taxes from masses despite all atrocities and heavy taxation. This period saw the rise of the introduction of the Daag shawl by one of the Afghan governors, which broke the backs of already burdened people.

Over the centuries, these pashmina-woven textile works of art, known simply as “kani shawls,” have been prized by Sikh Maharajas, Mughal kings, and European monarchs. Today, many of them hang in museums around the world, and in 2008, the Indian government gave these shawls a geographical indication, making it illegal for manufacturers in other regions to label their textiles. Kani shawls, among all Pashmina creations, are known to be the king of shawls.

The making process of kani shawls is a time-consuming one and a testament to excellent craftsmanship.

After sourcing the wool, the workers remove impurities, including hair, debris, or dirt, before transforming the wool into soft, fine yarn. After that, the white or brown yarn undergoes a dyeing process to manufacture the colourful yarns required for different Kani shawl designs. To transcribe the designs, unlike most weaving forms, the designs of Kani shawls are not imprinted or stamped directly onto the fabric. Instead, an expert (karigar) transcribes the design into a code known as ‘Talim’ on graph paper.

Artisans began weaving the shawls using wooden spools called tujje or kanis. They insert colorful threads, called wefts, into a curtain of warp threads using bobbins. Whenever the weavers need to add a different color to the design, two bobbins are joined, and this process continues until the Kani shawl is completed. Sometimes, the weavers may even use around 75 to 100 bobbins simultaneously to create the overall design of a Kani shawl.

"The focus and dedication required to craft a Kani Shawl design are truly remarkable. On average, an artisan can weave no more than one inch per day. However, this pace of weaving depends on the detailing and complexity of patterns or the design they are working on. Usually, it takes 3 to 36 months to complete one piece of pure Kani shawl," said Umar Jan, an artisan.

As time progressed, Kani shawls witnessed some major setbacks, affecting the functionality of numerous handloom crafts in Kashmir, which rendered the artisans unemployed and unpaid. Today, Kashmiri handicraft artisans are fighting for survival as the slump in the business has not only resulted in unemployment, but they also fail to pay the loan given to them under the artisan credit card.

"We have a family to serve, which we very unfortunately are not able to feed because of such low wages. Even working for days and nights together, we request that the concerned officials look into the matter seriously so we can live a comfortable life," said Fayaz Ahmad, another artisan.

Because of the consecutive lockdown for years in the valley, which resulted in a dropping tourist season, the Kashmiri handicraft business has been in vain, and so has the life of Kashmiri artisans in the workshops. Because of the economic recession, businessmen today can’t repay their investments, and so they are left with nothing to satisfy their artisans.

"We are and have always been aware of the issues faced by the artisans involved in the making of kani or other pashmina shawls. The government of India has been taking steps for their recognition by providing loans, awards, and artisan credit cards, as we understand that working under the patronage of renowned retailers doesn’t give them their desired amounts," said Mehmood Ahmad Shah, Director, Handicrafts and Handloom.

The journey of the Kani shawl from the loom to a globally acclaimed masterpiece is long. Original Kashmiri Kani shawls are expensive due to the meticulous craftsmanship and labour invested in their creation. However, with the advent of machine weaving, it is possible to replicate the renowned Talim patterns on machine-woven shawls. As a result, machine-woven Kani shawls are now commercially available worldwide at an exceptionally low cost.

While these imitations offer a similar look, they differ in quality from the authentic Kani shawls. It is crucial to find the delicate balance between preservation and evolution to grow the art of traditional Kani shawls in this rapidly changing world. Weavers are now exploring contemporary designs, colour palettes, and enhanced production methods to attract new consumers without compromising the authenticity that defines Kani craftsmanship.

In addition, the government has also taken initiatives to recognize the craftsmen and craftswomen through awards, fair wages, training programs, etc. to ensure the continuity of this art form. With an increasing emphasis on sustainable practices, the Kani shawl industry is also exploring eco-friendly bamboo modal fabric, dyes, etc. to revive the dying art of Kani weaving.

Manzoor Ahmad, a national awardee, has been making kani shawls for more than 25 years now. A science graduate, Manzoor picked art when he was 21, and since then there has been no looking back.

“I was the first person in my family to learn this craft. I always used to look forward to learning this art, and after my studies, I went to Bashir Ahmad, one of the finest artists Kanihama has ever produced, and started learning from him,” Manzoor said.

“My father was an Ari work artisan, but I became fascinated with Kani shawls in 1995 and have been working on them ever since. This form of art is not in my family lineage but rather something I picked on my own,” he added.

Despite the availability of machine-made shawls on the market, there is high demand for Kani shawls due to their unique handmade character. In some parts of the Valley, brides wear these shawls, custom-made by Kanihama weavers, as part of their family tradition. One of the most unique features of this shawl is that it looks the same on both sides. It stands out for its softness. Also, unlike other Kashmiri shawls, Kani shawls don’t feature embroidery work, and the different patterns are woven on the loom itself. The price of Kani shawls starts at Rs 35,000 and goes up to Rs 3 lakh. The cost may not seem steep when you see what goes into making a single piece. The demand for Kani shawls in India and abroad is high.

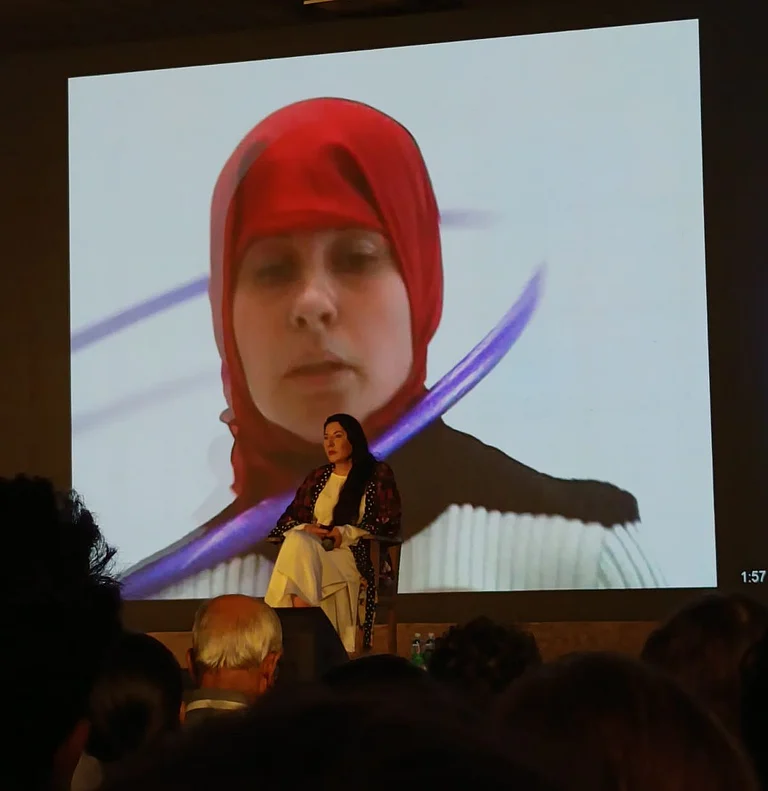

“The sale and demand of Kani shawls is wide and across the globe. Moreover, shawls worth Rs. 87 crores were exported this financial year, while the figure was Rs. 147 crores in the previous financial year. The CDI has started a pashmina testing laboratory, wherein fibers go through a microscopic examination to detect inauthentic produce. The reason being that even if one fiber is found to be impure, the whole lot gets rejected. But once it clears the test, it is labelled Kashmir Pashmina—a certificate of authenticity like Khadi Mark or Craft Mark,“ said Mrs. Amina Assad, Director, Craft Development Institute.

The only registered artisan bodies and weaving communities certified as pashmina and Kani weavers under GIA can send samples for testing. There are only 300 or so such certified weavers in Kashmir; the CDI also houses a pashmina bank that is run by J&K Small Industries Development Corporation, with pure fiber purchased directly from Ladakhi traders. The spinners can buy their yarn from it, she added.

The journey that awaits ahead for Kani shawls is one of both challenge and promise. It is high time to educate consumers about the craftsmanship and cultural significance of Kani artistry to foster a deeper appreciation for every piece of Kani shawl. By embracing the new and nurturing the power of the old, the Kani shawl industry can continue to weave its story into the fabric of the future.