The Surve family had always been a loyal audience for Marathi films. Every month, the family of five saved money and saw two films —Marathi and Hindi—in a theatre. Despite the family’s modest income, these outings had become a traditional bonding exercise for Manohar Surve, his wife Manju and their three children aged between five years to 10 years. However, the lockdown changed their perspective. Now they watch only Hindi films on the streaming platforms. The quota of popcorn is made in the family’s kitchen and other eatables are ordered through a delivery app.

“This is a much cheaper exercise. Marathi films do not have the same appeal as they did some years ago. We watched these films out of a sense of loyalty. We still do, but not as much as before. My wife likes to see the glamourous clothes, and I like to see the beautiful places shown in Hindi films,” Surve tells Outlook. This is not an isolated story. It is the emerging story of many of the middle-class film-watching households across Maharashtra.

According to sources, this industry is faced with a different issue—glamour versus content. Marathi films are going high on technology but lag in creativity. The younger generation of Marathi film viewers choose films that are not too serious but like historic Marathi films with a lot of visual effects. This generation is not too bothered about the aesthetics of a historical film. They are drawn to it for the special effects used.

Many historical films, particularly on the Maratha warrior king Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, are being made. One producer has made seven films on the subject. Sources say that films on Shivaji do well because Maharashtrians have an emotional connect with the Maratha king. In the 1930s, renowned film-maker Balaji Pendharkar made many historical films, including a few on the Maratha king. However, the large-scale historical films of today, are not as content-driven as the films made by Pendharkar, say industry sources.

With special effects taking on a big way, there is constant work for the technicians, who are making money. However, Marathi cinema has not become economically viable for producers, a trade analyst tells Outlook on the condition of anonymity. “Many builders with deep pockets have turned producers. They want to invest their money, and Marathi films have become a good parking zone for doing this,” reveals the source, who further adds that these producers are not too bothered about the losses as Marathi films are not too high on the budget front.

“To park their investments, these builder-producers increased the film's budget. But this superficial increase saw a collapse. Intelligent themes do not get sold. Once, rural themes were loved by the audience, but the present-day audience is more attracted to glamour. The storyline, too, does not matter. Glamour rules as it is used in making Instagram reels and videos for social media,” says an actor turned producer.

Marathi films are finding it difficult to get producers with deep pockets as those who were in this industry have now migrated to the Hindi film industry. “Marathi films have good actors but cannot draw in an audience or money. Producers have stopped investing in talent, they are now investing in the returns their films can fetch,” says a former Marathi A-lister actor, who reveals he was dropped from a production citing the reason “his face had lost its appeal”.

Marathi films are released in only four cities in Maharashtra—Mumbai, Pune, Thane, and Kolhapur. “These films are never released in Konkan, Marathwada or Vidarbha because these are not the revenue segments. For years on end, it is these four cities that have seen the releases. No experimenting has happened beyond these cities,” points out Ashok Rane, a well-known film critic and three-time recipient of the National Film Awards. “Producers are drawn to Marathi cinema and go ahead and make films too, but the flip side is that they do not come back to make another,” he tells Outlook.

Those in the know pointed out that after the Covid-19 lockdowns, the industry is in a state of disarray. When the theatres opened after a two-year gap, about 300 Marathi films were ready for release, but theatres were not available to screen the shows. Hindi films remain the first preference of theatre owners—single, small multiplexes and larger multiplexes.

A writer who was made to change his storyline at least 20 times to make it more “market-friendly”, reveals that Marathi filmmakers are in a tearing hurry to make films. “As if they are in some competition on the number that must be made. They do not give time for the film to be made, so there are hardly any memorable Marathi films now. It is always the past glory that is referred to,” this writer tells Outlook, anonymously.

To understand why this industry appears haywire today, it is best to go back to its beginnings, says Rane. 1932 was when Marathi cinema was launched. Till 1960, this industry saw a lot of filmmakers getting into the arena and making Marathi films. They were small budget films as the nascent industry did not draw much money. The film Sangte Eika (1952) paved the way for gramin (rural) cinema. The lifestyle of rural Maharashtra was showcased in this film, which created an instant bonding with the audience. Sangte Eika ran for a record 135 weeks. Following its success, many films were made on the same lines. For the first time living in rural Maharashtra, which included lavani and tamasha, came out of the rural makeshift drama theatres. This created a strong connection with the audience, largely comprising the middle and lower-middle classes. This segment of viewers dominated the audience until 1960.

However, between 1960-70, the Marathi film industry was in the doldrums. There was a severe financial crunch and filmmakers were shying away from taking on new projects. At this time, well-known director V Shantaram approached the state government to provide some tax relief to the industry. The Maharashtra government introduced the Tax Refund Scheme, which gave a boost to Marathi cinema. About 20 films were made then made in a year.

In 1970, Shantaram made the iconic film Pinjra—the first Marathi film in colour—with Dr Shreeram Lagoo in the lead role. This was a runaway hit, say filmmakers pointing out that the film's success has not been emulated thereafter. Unlike the Hindi film industry, which saw a moneyed class enter filmmaking, the producers in the Marathi film industry were not flush with funds. Though the Tax Refund Scheme brought in much-needed relief, its binding clause was that a producer who availed of this scheme's benefits had made another Marathi film. This saw producers stay on in the industry, which led to good cinema.

Around this time, popular comedian Dada Kondke entered Marathi films and brought with him a unique kind of comedy that would have the audience in splits. Kondke’s style of dialogue delivery and his rural way of dressing and dialogue delivery kept audiences hooked. He made comedy popular, and it emerged as a mainstay in films that were made in the later years. “Marathi films have the longest history of comedy. Even today, comedy is the most popular genre,” says Rane. However, the upper class and the educated kept away from the innuendo-style comedy popularised by Kondke and later by Makarand Anaspure.

In the 1980s, two urban actors Sachin Pilgaonkar and Mahesh Kothare ushered in the era of films with urbane themes. The actors who followed Pilgaonkar and Kothare into the industry were younger and very urban. Alongside the rural cinema entered urban themes. These two actors ruled the 1980s decade, which saw the box office concept of silver and golden jubilee emerge in Marathi films too.

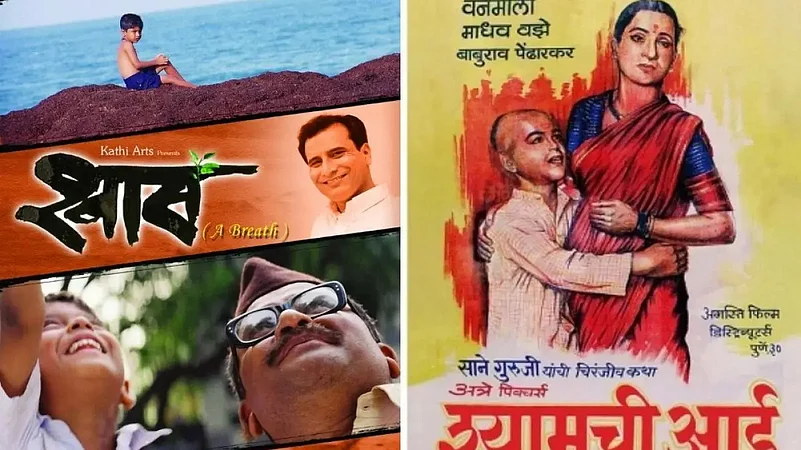

From 1990 till 2004, the industry grew stagnant. “The proximity to the Hindi film industry was damaging Marathi cinema. Despite the accumulating losses, the traditional producers were still very much on the scene. In 2004, the film Shwas won the National Award in the regional films category, and it in a way became a turning point for the industry. The first Marathi film to win this award was Shyamchi Aiyee in 1952 and Shwas won after 52 years. Insiders say this gave a new buoyancy to the industry, as Shwas had also won an Oscar nomination. Since 2004, Marathi actors have been consistently bagging National Awards.

A Bollywood director, who recently ventured into Marathi cinema, says he was disillusioned by the situation. “Hardly any research is being done on the subjects. It is extremely superficial. Many of these directors come from a theatre background and think it is easy to direct films. I worked alongside a top Marathi director, who is also an actor, but he had no clue about the workings of the industry. This industry is driven by insecurities and mediocre talent,” the director reveals, choosing to stay anonymous. At present, the elite masses are not regular watchers of Marathi films, and for the middle-class Marathi Manoos, the first choice is Hindi films, then dubbed English films, with Marathi being the last choice. “Heroes and heroines in these films are shown as regular people. When the demand is for glamour, why will anyone pay to watch the common man and his problems with celluloid?” Rane poses a valid, albeit poignant query.