Mohammad Usman, 60, sits on the floor near a wooden frame which holds the cloth that he is crafting so delicately. He is embroidering a cover for the Jewish Bible.

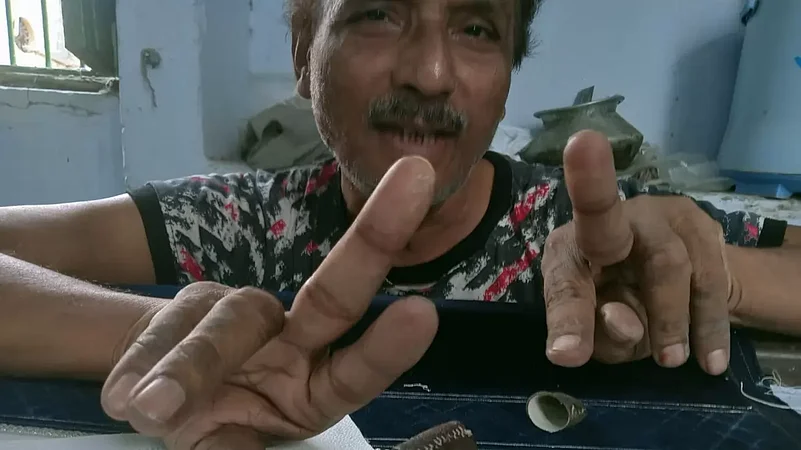

“I have been doing this for 50 years,” he says, taking off the rubber band-aids from his fingers, unveiling the punctures left by countless needles he has worked with in these years.

Sitting in one posture with his eyes fixed on the design, he works for 12 hours a day and struggles to make Rs 250. The piece he is working on will be exported to Israel soon.

“I gave my whole life to this craft, but it gave me nothing,” Usman laments.

The craft of zari-zardozi is an artform that involves embroidering brocade, silk, or velvet with golden and silver threads, often along with beads and sequins. A historic artform tracing its descent from the Mughal era, zari-zardozi has for long served as a livelihood to a majority of the Muslim population in the city of Bareilly in Uttar Pradesh. However, for the past few years, this shimmery domestic industry has been in the dark, having left in gloom thousands of workers in the city.

Usman's co-worker Afzal Hussain displays another beautiful artistic creation.

“This one is a neck-collar for the dress of the Jewish pastor,” Afzal explains, placing the piece around his neck in an effort to imitate the pastor. “Such is our condition that nobody wishes to marry off their daughter to a zari karigar,” says the young man when asked about work.

Usman tells about two of his co-workers’ deaths.

He says, “Both of them looked well when they came in the morning, but you can’t say about stress. It took them both away. They died apart, but the same way. I may die one day too. But, who will feed my family after me?"

Usman’s remark evinces the fear of hunger. But Ghulam Rasool's story is a living translation of Usman's dread of starvation. The only bread-winner among eight members of his family, Ghulam works at a zardozi karkhana —workshop— in Bareilly and struggles to earn Rs 200 a day. However, last week’s doubling down on the effort brought him Rs 2,000. He had an old loan of Rs 1,100 from the local grocer, so he considered paying it off in part, but little did he know that the grocer would heartlessly ignore his plight and demand the whole of his sum.

He says, “As if this was not enough, my landlord then asked me to pay another Rs 800 for electricity, threatening me with a supply-cut.” This left him with Rs 100 on the day his son fell ill with diarrhoea. “My wife and I faced the toughest dilemma that evening. We agreed to not have food cooked in the house that night, but take our son to the doctor. Shame on my fortune. My children went to bed hungry.”

The LoC of development

Zari-zardozi has always served as a subsistence aid to the economically indigent section of women in the city. Homemakers and unmarried girls can be easily found adorning suits and dresses with studs and metallic thread in their homes.

Girls most often convert their homes into makeshift karkhanas to amass funds for their marriage. Married women, on the other hand, use their earnings for household expenses. But with the nearing collapse of the industry, women workers are losing the financial liquidity they once enjoyed.

This reporter reaches Baqarganj, a Muslim ghetto located across the railway line. The iron track, reflecting the sun rays, lays audaciously like an LoC of whatever development there is. It is in an effort to isolate the mohalla from the city.

In one of the houses, Aashna carries out zari with her two sisters. The house is an old-fashioned one; a courtyard leading to the verandah and a crumbling room. In one corner is placed a gas cylinder that has not been in use for long. The prices have gone up too much, so we now cook on this, Aashna explains, pointing towards an earthen stove, her voice echoing the debacle of Ujjwala Yojana.

She is set to get married next month to a boy named Afsan, someone whom she has never seen but in photographs. There are no fixed wages for women like her; they get paid per piece. The one Aashna is now working on would fetch her Rs 250. This is her second day of work on the segment. “It is a heavy dress, so it will take some time,” she tells this reporter.

The business had already started to go down the line and the lockdown made up for the rest, she says. “The value of our work is only falling. It is not keeping up with the inflation,” she says.

Aashna would earn a mere Rs 80 a day even if she completes this assignment in three days. Her account illustrates how poorly paid are women zari-workers.

In another such house, Babbo and Iram sit on a raised coarse platform near the zari frame under a tin-roof supported by bamboo sticks. In the backdrop plays a qawwali. The lyrics say, "Allah nigehbaan hai duniya mein sabhi ka." (The almighty is the protector of all beings in the world)

Iram, an eighth-grade student, lost her father to a chronic ailment a month ago. She sits with her cousin; a hooked awl in her hand, she seems to have mastered the art. On an average, she makes Rs 80-100 a day.

Babbo, who has been doing this for 15 years, compares her current earnings with those before the lockdown, saying “Where we used to make 250 in a row for a suit, now it is difficult to earn even 150 for the same design.”

The person who supplies us with work says that the cost of material has gone up and, by that reason, they have no work to pass on to us, Babbo says.

A shared loss

Back in main city and its hustle-bustle, Qahid Raza, a raw material retailer, awaits his first customer at 1 pm. He is carrying forward his father’s 32-year-old business of retail.

“A few years back, my turnover ranged from 30 to 40 lakh. Now, it does not even reach 5 lakh a year,” Raza mourns his loss. He believes it is the apathy of the authorities towards the state of this craft that is responsible for their plight and the coming up of computer designs only added fuel. “I sense no betterment,” he declares, dejected.

Like any other local business sector, zari-zardozi also entails the fusion of numerous small firms in the form of people employed at various sectors, performing different work.

A few footsteps away, just opposite to an old sufi shrine, Saleem sits on the footpath with his make-do wooden counter that contains tiny, little boxes of every variety of needles that there are — a hooked-tip awl or an ‘aari’, a long needle for beads, another set for silk threads, and many more in different measurements.

“There was a time I used to make Rs 400-500 a day, but today earning Rs 200 is a big deal,” says Saleem. His three sons also work as karigars in a zari karkhana and struggle to meet their ends.

It is not just Saleem. Another needle-wholesaler Zakir alias Babbu, an erstwhile karkhandar—workshop-owner— also has a similar story. He has also been running a wholesale-business of zari-zardozi needles for 30 years now.

“I had to shut my karkhana because there wasn't any way out. I had been caught in the trap of shopkeepers,” Zakir tells this reporter. “They would pay me partially and hand over another assignment only if I agreed to comply with their payment dates.”

“My needle business has been in decline for some six-seven years now,” says Zakir, adding that first demonetisation and then GST coupled with the recent lockdown brought him down. “I used to earn Rs 30-35,000 a day, but now this work does not fetch me more than Rs 2,500. I have shifted on to the business of making garlands of currency notes.”

The preparation of a khaaka —design— is the first step in zari-zardozi and Arshad has been doing this for 30 years. On the first-storey of an old building, the door of his house wide-open, he can be seen lying in his bed. He is listening to a video on Babri Masjid when this reporter knocks at the door. When asked about his work, he outrightly says that there is absolutely none of it for long.

“I had to move on to my own hair-oil business,” Arshad adds. He believes that the downfall of the industry is here to stay.

Tiny beads and sequins lead to a small workroom. The board inside reads Jamal Courier. Near to the door sits an old man whose business lineage is now managed by his son Jamal Khan. He says, “Matters have gone worse. Jamal must be coming soon.”

His son comes in a while. When asked about the business, his response echoes his father's dejection. “My work is down to 50 per cent of what it once was.” He adds that the rise in petrol and diesel prices have made matters worse.

From craftsmen to labourers

Among the hard-hit lot are also people who out of compulsion of their deplorable condition in zari changed their lines of work. One such person is Mohammad Arif. An erstwhile karkhandar, Arif can be seen with his vegetable cart at the side of a road in Kankar Tola, a majorly Muslim locality in the city. He is in an argument with a customer over the rate of potatoes. "Inflation is high,” he says.

“Some 25 karigars worked under me until four years ago,” Arif starts his tale. His sari-line business had a turnover of Rs 1.5-2 lakh a month. But, things started to go downhill for him with the coming of GST and the growth of Surat's embroidery industry. “When matters became worse, I started this vegetable stall on a friend's advice,” he continues.

Arif works 18 hours a day now and wakes up at 3 am to fetch fresh stock from the market. “I make Rs 700-1,500 a day with this,” he says.

“Zari was a respectable job, this isn't,” he adds. “If business picks up again tomorrow, I'll start right away.”

Shadab's is another story. His father Munna was a big kankhandar in his time, but his son now works in a slaughterhouse in the city for Rs 10,000 a month. “I took over the business, but after some years, the domestic saree-line started to decline,” Shadab explains.

Starting with demonetisation, then GST, and computer design along with the rise of Surat industry, my work was only getting worse.

He says, “Sometimes, I feel like crying.”

Sajid, once a karigar, has been driving an e-rickshaw for five years. “My karkhandar would never pay me on time,” he recalls. “I had to wait for a Friday to get my children what they desired and then the karkhandar would call the payment to a Saturday.”

When asked if he missed zari, he asks, “What good is it to recall work that makes you starve?"

Sajid’s escape accentuates Usman’s fear and Ghulam Rasool’s tragedy. But, if this escape keeps replicating in years to come, zari-zardozi would not survive long.

Hope is a far-fetched idea

A recent development in zari-zardozi has been in the shawl-line. Sajan, who has been a karkhanadar since 1996, displays a shawl that his karigars have embroidered lately. A paragon of handicraft finesse, the shawl is embroidered with a village scene in countless colours of thread. But, again, the remuneration paid to the karigars is not commensurate with the hard work they put into it. Afsar's response clears all doubts. He is a karigar in Sajan's karkhana.

“The wage depends on your speed. With this speed, I earn Rs 200-250 a day,” he says.

Albeit, distinct because of their stories, there is one thing barring pain that unites the people associated with zari in Bareilly. It is their longing for some assistance from the government which they hope would better their situation or at the very least end their hunger.

The rosy government files

An official at the District Industrial Centre, Bareilly, tells about the achievements of the One District One Product (ODOP) scheme for the zari-zardozi craft. As part of this scheme, 400 female individuals are to be imparted with zari-zardozi training and given a toolkit after the completion of the training.

The records say that in 2021, the scheme achieved its overall target. “In 2022, too, we have achieved the target of training 400 females,” the official says.

However, when asked for the list of beneficiaries, he backs out, outrightly rejecting this reporter’s request. The reporter tried to fetch the list through other sources, but in vain.

When enquired about the loan scheme for zari-zardozi craftspeople, the official puts forward the data.

“In 2021, we were provided a sum of 2.75 crore along with a target of 110 individuals, but because the number of beneficiaries increased to 128, the amount of loan reached 304.45 lakh,” said the official.

The current data shows a rosier picture. Considering the past achievements, the government has increased the loan amount to 300 lakh with a target of 71 individuals. The data till September last year says that 195.06 lakh rupees had been given to 41 people.

The One District One Product (ODOP) Scheme, which is more of a misnomer, includes zari-zardozi, jewellery, and cane-work in Bareilly. Sources tell this reporter that the budget allotment concerning the Common Facility Centres (CFCs) has been quite erratic. However, officers in the city do not wish to talk about the problem.

Although the targets of such schemes have been increasing, they do not seem to have any effect on the ground. No matter how big and ambitious they sound, they remain insubstantial for most of the zari-workers.

Afsar declares, “We never know when such schemes are launched. It is only a handful of people who know how to get through the maze that have been able to get some aid.”

A recent effort at increasing industrial investment in the state has been the Uttar Pradesh Global Industrial Summit (UPGIS). The first chapter of this Summit was held on January 24 in Lucknow, the proceedings of which were telecast live at the Indian Medical Association (IMA) Hall, Bareilly.

The district of Bareilly had been given an initial target of Rs 3,000 crore which was later revised to Rs 4,500 crores. Joint Commissioner of Industries Rishi Ranjan Goel and District Magistrate Shivakant Dwivedi along with officials called in investors for the signing of memorandums of understanding (MoU) and according to a source that this reporter contacted, the target of MoUs was overachieved by approximately eight times by mid-February.

Out of the 540 investors —the number could vary with time— that this reporter could access information of, only 14 were directly connected with zari-zardozi, the highest investment being of Rs 10 crores.

An investor who agreed to talk on the condition of anonymity said that the government considers property and building investment to be a mere 10 per cent of the total amount of the MoU signed. Moreover, for this, it wishes to allot property in the government-owned industrial areas instead of urban localities of the city where most of the people associated with zari zardozi live.

Another field of investment is of design studios where designers associated with zardozi can design and curate dresses to be further worked upon. However, the conditions of the scheme to be under 35 years of age and a graduate-level degree from a fashion institute are too hard to be met by ordinary people associated with the craft.

When contacted, one of the zari investors in Bareilly said that he was not acquainted with the proceedings after signing the MoU and that he had only heard from people of how the government would take things forward.

Shameem Ansari plans to invest Rs 1 crore for the expansion of his showroom. Once the investment is made, he is hopeful that the government would provide some subsidies and reimbursement, although when that would happen remains a question unanswered. With the slow pace of the market and the decline in demand, it has become all the more difficult to invest in zari-zardozi, Shameem says.

Mukhtar Ahmad Ansari has also submitted an application for the MoU of Rs 1 crore concerned with investment in zari.

“Consider it a matter of luck if I am given a loan of Rs 50-60 lakh out of Rs 1 crore,” says Ansari.

When asked if the ODOP scheme has benefited the sector, he responds with a couplet of Ghalib, “Humko maaloom hai jannat ki haqeeqat lekin, Dil ke khush rakhne ko Ghalib yeh khayaal achchha hai." (I am aware of the truth of heaven, but the thought is appreciable to let the heart be distracted.)

While investors invest and political leaders attend these events, thousands of karigars like Usman, Afzal, Aashna and Iram only stand by to search for Ghalib's undiscovered jannat.

Meanwhile, Ghulam Rasool awaits another Friday for his payment.

“I don't know what to do now. I have absolutely no money,” he declares, a large tear-drop falling on his hand. Unseen, it looks like a zari-bead, an ignored pearl that has long lost its lustre.

(Madeeha Fatima is an independent journalist currently based in New Delhi. This story has been reported under the National Foundation for India’s Fellowship for Independent Journalists 2022.)