Wearing a green shawl on his right shoulder, Chandrashekar, a 60-year-old farmer leader from Karnataka’s Mandya district, arrived at the interview location in just about five minutes after a brief phone call. He stands under the shade of a large banyan tree, wiping the sweat off his forehead with the cloth. “I am never usually this free,” he says, catching his breath. Chandrashekar, like most farmers in the sugarcane bowl of the state, used to spend a good part of their afternoons on the field, growing bhatta (paddy), sugarcane and ragi. But in this scorching hot mid-April afternoon, farmers in Mandya find themselves idle. Their fields have run dry, and so have their main sources of income. A palpable sense of anger looms across the farming belt of Mysuru and Mandya, which are situated amid the tall pine trees and paddy fields in southern Karnataka. The region is also traditionally known to be the Vokkaliga heartland of the state. A predominantly rural community that is associated with farming, the Vokkaligas are key to any party’s electoral performance in southern Karnataka. In the months leading up to the Lok Sabha elections, the farmers here weren’t asking for a lot… they just wanted neeru (water).

The Fight for Cauvery

The Cauvery river, which many consider as sacred in south India, rises in the Western Ghats at Talakaveri, flows across the Deccan plateau in south India through the states of Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Puducherry and then into the Bay of Bengal. The dispute over the river water dates back to the pre-Independence era when the then princely states of Mysore (now Karnataka) and Madras (now Tamil Nadu) contended for control over the river’s waters.

Cauvery’s water serves as a lifeline for farmers in both Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. After a lot of back and forth over which state should get how much water, the final water-sharing arrangement was decided on the basis of the Cauvery Water Dispute Tribunal’s award in 2007 and a Supreme Court judgment in 2018. The current anger among farmers stems from the state government’s decision in September 2023 to adhere to a Supreme Court order and release 5,000 cusecs of water per day to Tamil Nadu. “Our state gave water to Tamil Nadu when we ourselves were struggling,” says Chandrashekar. Last year’s southwest monsoon played spoilsport, especially in south interior Karnataka. Between June 1 and September 23, the region suffered a rainfall deficit of 27 per cent, according to the India Meteorological Department (IMD).

Most of the farmers’ fields are very close to the Krishnaraja Sagar (KRS) Dam, which is constructed across the Cauvery water. Many of their crops have died and they don’t have enough water to grow new ones. “Even though the KRS dam had water, a play of politics led the government to give this water to the neighbouring state. We have incurred huge losses due to this,” says Somashekhar, another farmer from Mandya. He claims that the Siddaramaiah-led Congress government did not want to upset their INDIA bloc partners in Tamil Nadu, and hence, provided them Cauvery water.

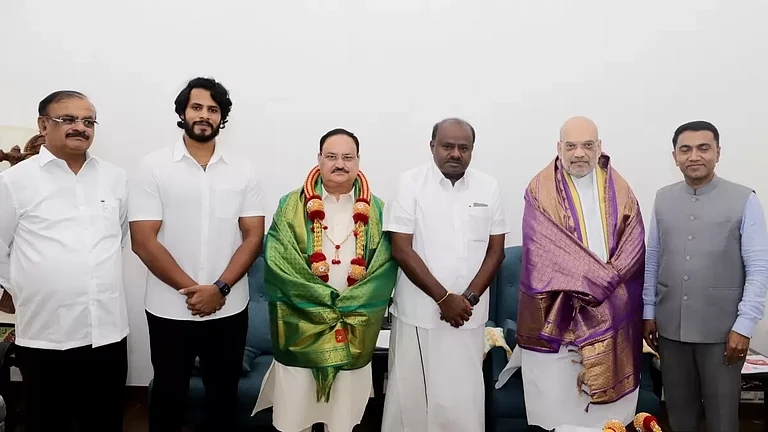

While the Union government has stayed away from this emotive issue, leaders of the state unit of the BJP and the JD(S)—both parties are in an alliance in this election—often use the ongoing water scarcity situation in their barbs directed at the Congress. The JD(S), which is headed by former Prime Minister H D Deve Gowda, has projected itself as a party that works for the welfare of farmers. By allying with the BJP this time, farmer leader Kuruburu Shanthakumar says, both parties could have an electoral advantage in south Karnataka amidst the farmers’ anger with the Congress party.

The Angry Farmer

In Mysuru, a group of 10-15 farmers went into a huddle to air their grievances. There was one leader, Shanthakumar, who was jotting down what the farmers were complaining about: burden of debt, lack of pension, demand for Minimum Support Price, etc. Shanthakumar didn’t seem to have any solution. “We are preparing our own manifesto and whichever party agrees to our demands, we will support them,” he declares. They called out both the Union and state governments for remaining ambivalent on issues raised by farmers. Some of these farmers also accompanied their counterparts in Delhi and Punjab during the protests against the Centre demanding implementation of the M S Swaminathan Committee’s recommendations. “Sometimes when a farmer leader from Punjab sends a pamphlet, we use Google to translate and understand what they’re saying,” Shanthakumar says. But we are all fighting the same fight, despite language barriers, he reiterates. They had gathered near a statue of Kuvempu, a revered Kannada poet of the 20th century. Back in 2020, when the BJP government was in power in the state, a revision committee headed by Rohith Chakrathirtha allegedly distorted facts about Kuvempu in the revised social science textbooks. The JD(S) and the Congress leaders were extremely critical of the Basavaraj Bommai-led BJP government for doing so. Four years later, the political landscape of the region looks different.

The JD(S) is supporting the BJP’s activities in the state. The Congress government, riding high on its welfare-related initiatives, has now reportedly dropped the contentious textbook revisions. The grand old party, however, finds itself at a crossroads with angry farmers in the state.

Attempts to Polarise

To reach Mandya from Bengaluru, one has to use the Bengaluru-Mysuru expressway opened by the Union government last March, in a bid to not just reduce the time it takes to travel between the two major cities, but also to reach the hearts of Vokkaliga voters. That road, which was constructed by cutting villages into half, seemed a bit too bumpy for the BJP. First, the saffron party made desperate attempts to polarise the community with the infamous narrative of two fictional Vokkaliga characters, Uri Gowda and Nanje Gowda—and that the two, and not the British, had killed the ruler of Mysore, Tipu Sultan, in the fourth war of Mysore in 1799. Then, it scrapped the four per cent reservation for Muslims and distributed it between the Vokkaligas and the Lingayats. However, the party didn’t make any gains in the region.

Lakshman Cheeranahalli, an advocate and activist in Mandya, reiterates that the BJP’s politics of polarisation does not strike a chord among the Vokkaligas who have always believed in treating everyone equally. Hailing from a farming community himself, Cheeranahalli recalls how Tipu Sultan helped them get land reforms. “But the BJP projected him as a desh drohi,” he says.

Mandya has a long history of caste politics. So far the district has not chosen anyone other than a Vokkaliga to be its MP or MLA. But locals in the region say there has been a slow yet dangerous shift in the political narrative. “Mandya is now seeing communal tensions instead of caste conflicts,” says Cheeranahalli. Communalism is always more dangerous than casteism. However, it is not going to work,” he says confidently.

Political analysts say that this will be a battle for survival for the JD(S), which once dominated the political scene in the Vokkaliga constituencies of the state.

A renewed attempt to saffronise the region was seen early this year. Hijab, Halal was old news… this time it was about a Hanuman flag. Deep within Keragodu village in Mandya district, a 108-foot flagpole stood tall, and undisturbed, until late January this year. Gram panchayat authorities decided to replace a Hanuman flag that was hoisted atop the pole, with the Indian flag on January 28. While locals in the region say that the practice of hoisting a religious flag—in this case a Hanuman flag—dates back several decades, gram panchayat officials maintain that they had given permission only for the national flag and Karnataka/Kannada flag to be hoisted, with no allowance for other religious/political flags.

This happened around the same time the grand consecration ceremony of the Ram Mandir took place in Ayodhya, which the Congress had boycotted. The Mandya flag issue gave the BJP-JD(S) leaders more ammo; they alleged that the Siddaramaiah-led Congress government was against ‘Ram’ and is ‘anti-Hindu’, while Congress leaders accused the saffron party of inciting ‘communal tensions’ ahead of the elections.

Bandhs were declared. Marches were called. Chants of ‘Jai Shri Ram’ echoed. JD(S) leader and H D Deve Gowda’s son, H D Kumaraswamy, arrived in Keragodu, sporting a saffron shawl, instead of the usual green. He made public appearances with right-wing organisations, supporting their call of hoisting saffron flags in every household. These visuals came days after Kumaraswamy attended the consecration ceremony of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya—a move that was in stark contrast to his earlier criticism of the BJP for ‘misusing Ram’s name for political benefits’ (in February 2021).

Almost three months after the row, the divide seems clear in Keragodu village. A blanket of saffron flags with a picture of Hanuman could be spotted from miles away—something that is rare in a Vokkaliga-dominated region that has been under either the Congress or the JD(S) rule. The Hanuman flag was brought down, but was still stuck on one side of the flagpole. The Indian flag was now hoisted on the top. A police van has been making its way to the spot every day since January. Around 4-5 barricades encircle the flagpole: “To protect it from people or to protect people from it?” asks a local shopkeeper in amusement. He says the situation is calm now. “It was never an issue before. We had Hanuman flag, but the Congress government made it into a big issue,” a tea vendor claims.

However, farmers in the region do not mention the Mandya incident even in passing when asked about their main concerns in this election. In fact, the incident, Cheeranahalli says, was an attempt to divert the attention from the primary concerns of people in the region: drought, the Cauvery river water dispute, farmer suicides and unemployment. “My god is also Hanuman,” he clarifies. “But when these political parties invoke God, it is often not just limited to one’s faith,” says Cheeranahalli.

Unlike the other south Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh, where regional parties have flourished, the JD(S) in Karnataka has struggled to create an identity of its own. Often touted as the ‘kingmaker’ of politics in the region, the JD(S) has allied with both the Congress and the BJP, despite its initial commitment to stay independent of the two dominant political parties.

On the ground, however, the JD(S) and its leaders still find resonance among some farming communities. The party usually fields a majority of its candidates from the Vokkaliga community and has been known for its focus on the rural poor and farmers’ issues. Further, the grassroots appeal of Deve Gowda continues to this day. Progressive farmer Krishnappa K T recalls Gowda’s lifelong commitment to the farmers’ cause. “The farming community will always vote for Deve Gowda and his JD(S),” he says.

The saffron party too realises that it cannot win a majority on its own without the support of the old Mysore region. Hence, both parties have found an ally in each other this time, though they have publicly criticised each other in the past. But some farmers are equally critical of the ‘family politics’ that they say JD(S) indulges in. With the announcement of candidates for the ongoing elections, it became clear that at least nine members of Gowda’s immediate family are or have been part of electoral politics. Political analysts say that this will be a battle for survival for the JD(S), which once dominated the political scene in the Vokkaliga constituencies of the state.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Anisha Reddy in Mandya and Mysuru districts

(This appeared in the print as 'A Vote For Water')