Union minister Sarbananda Sonowal is one of the two best-known sons of Chabua, a small town neighbouring the major commercial hub of Dibrugarh in upper or eastern Assam. The other is Paresh Baruah, the fugitive chief of the banned separatist organisation, United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA), who is rarely in the news these days. Now, two decades after his big-bang entry into state politics, Sonowal has many detractors in his hometown.

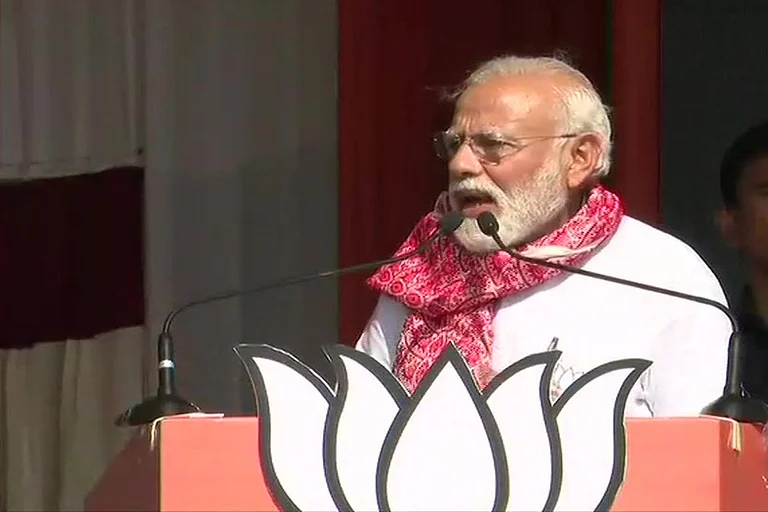

“Narendra Modi is great, Modi should remain the prime minister, but Lurinjyoti [Gogoi] can serve our Assamese purpose better,” says Nipul Saikia, a small trader at Chabua, sitting at his shop, sipping his cup of Assam tea.

The contradiction in Saikia’s wishes had to be pointed out. Gogoi is an opposition candidate from the Asom Jatiya Parishad (AJP), a party launched in the aftermath of the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) protests. CAA protects Hindus of Bangladeshi origin from the citizenship screening exercise, the National Register of Citizens (NRC) for Assam. His victory would mean the defeat of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)’s Sonowal. And that would not help Modi secure a third term as PM. To this, Saikia nonchalantly responded, “Country is a big thing. If we think of our constituency, Gogoi is energetic, educated and dynamic. He has been uncompromising on the questions of Assamese identity. He should get a chance.”

A few hundred metres away, a group of youths echo him. They are workers of the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), an ally of the BJP. The Chabua MLA belongs to the AGP. The party, currently much weaker than in the past, still has a significant presence in the town. “We are campaigning for Sonowal, but the contest might be closer than what the party thinks. Many people are saying that Gogoi should get a chance as Sonowal has already got his fair share of chances—as an MP, chief minister and Union minister,” says one of them.

Asked if they too are in favour of Gogoi, one of them responds, partly embarrassed, partly amused, “We are with the BJP-AGP alliance. We just told you about an undercurrent we sensed during the campaign.” Others in the group giggle as he speaks.

Of Assam’s 14 Lok Sabha constituencies, five are in upper Assam–Dibrugarh, Jorhat, Lakhimpur, Sonitpur and Kaziranga—all of which go to the poll in the first phase on April 19. Assam’s BJP chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma has ruled out any contest in any of these five seats, claiming they will all be a cakewalk for the party.

Demographic change has been a dominating factor in Assam’s politics for over four decades. However, the upper Assam region has seen little demographic changes compared to lower Assam, where Muslims and Hindus of Bangladeshi origin constitute a large chunk of the population.

While Assam’s ethnic politics has been against both Hindus and Muslims of suspected Bangladeshi origin, the BJP’s rise has shifted the focus against the Bengali-speaking Muslims.

“In Assam, where the faultlines have traditionally been linguistic and ethnic, not religious—we now see that Hindutva politics is slowly undermining Assamese sub-nationalism,” says Guwahati-based journalist Tora Agarwala. “The BJP has successfully managed to portray itself as the saviour of the ‘indigenous Assamese’, yet stemmed the opposition against the controversial CAA that saw widespread protests in 2019 and 2020.”

According to Agarwala, this, along with a massive development push, has helped the BJP in constituencies in upper Assam, which is considered the bastion of Assamese sub-nationalism.

In upper Assam’s Dibrugarh and Jorhat, opposition parties are trying hard to revive Assamese ethnic politics. In Dibrugarh, Sonowal is facing AJP’s Gogoi and Manoj Dhaowar of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP). Dhanowar holds some influence in the tea gardens. His father was a respected leader among the tribes living in the gardens.

AJP, another regional party Raijor Dal, and several Left parties have come together to form the Congress-led United Opposition Front, Assam (UOFA). In Jorhat, state Congress heavyweight Gaurav Gogoi is the UOFA candidate. The UOFA is positioning the Dibrugarh and Jorhat candidates as “the best voices to serve the Assamese purpose in New Delhi.”

Sixty-one-year-old Sonowal and 47-year-old Lurinjyoti Gogoi have the same roots—the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU), which has been at the heart of Assamese identity politics. Sonowal headed it in the 1990s and Gogoi from 2015-20.

Sonowal, currently a member of the Rajya Sabha, breached the Congress bastion of Dibrugarh Lok Sabha as an AGP candidate in 2004. He joined the BJP in 2011, won the neighbouring Lakhimpur Lok Sabha seat in 2014, and served in PM Modi’s ministry from 2014-16, before serving five years as Assam chief minister.

In Jorhat, the contest is expected to be between the BJP’s incumbent, Topon Gogoi, and Gaurav Gogoi, the deputy leader of the Congress and son of former Assam chief minister Tarun Gogoi.

Going by the arithmetics, the BJP is ahead of others in both Dibrugarh and Jorhat. Even though parts of Dibrugarh and Jorhat witnessed violent anti-CAA protests in 2019, the BJP managed to win most of the assembly seats within the Dibrugarh and Jorhat Lok Sabha boundaries in the 2021 state election. In Dibrugarh, they secured about 52 per cent votes. In Jorhat, the boundary of which has been redrawn, the BJP secured about 54 per cent of polled votes.

Mohanbari resident Phani Bhusan Chetia points out that while the young generation may vote for AJP’s Gogoi, the party would face the hard task of familiarising the vast majority of the rural masses with its symbol. “Most people know the symbols of the Congress and the BJP. The new symbol will be one of Gogoi’s biggest disadvantages. Besides, state government schemes like Orunodoi and Lakhpati Baideo are quite popular among women,” he says.

In Jorhat, the opposition is focusing on Gaurav Gogoi’s performance as a parliamentarian, how his participation in debates, asking questions and bringing private member bills were higher than the national average, whereas the BJP’s incumbent, Tapon Gogoi’s participation was much lower than the national average. “Do you want Assamese voices to be heard louder in Delhi? Then elect Gaurav Gogoi,” reads one pamphlet issued by the UOFA.

In lower Assam, the issues change significantly as the Miya community occupies a significant part of electoral discussions.

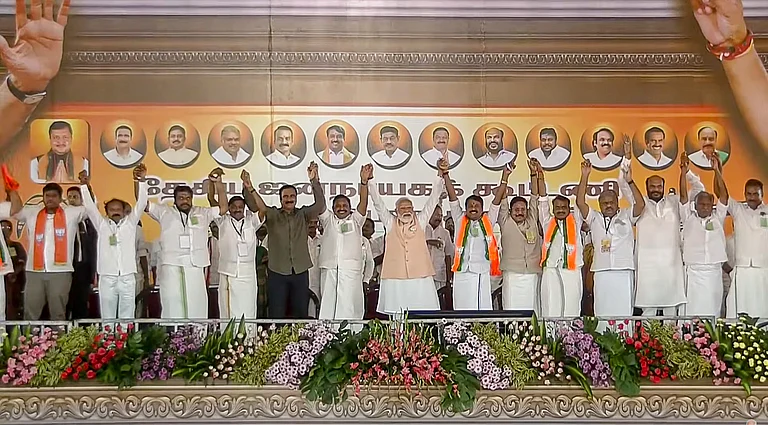

The BJP, apart from PM Modi’s development schemes and strong leadership, is highlighting how the prime minister paid his respects to Assamese identity by inaugurating a 125-ft statue of Assamese icon Lachit Borphukan in Jorhat town.

According to Kaustubh Kumar Deka, a political scientist at Dibrugarh University, Jorhat has drawn a lot of attention due to the “Gaurav Gogoi phenomenon” but he is not sure if such an emotive appeal can swing votes sufficient enough to pull off a victory over the BJP. “Past experience shows people are voting based on the benefits of development schemes. The tribes living in tea gardens have a significant role in deciding the fate of the constituencies but Assamese identity politics doesn’t appeal to them,” he told Outlook. He pointed out that in both Jorhat and Dibrugarh, the emotions and on-ground consolidation against the CAA could not dent the BJP’s prospects in the 2021 assembly elections, which reflects a disconnect between emotions and public sentiments and the voting pattern.

In lower Assam, the issues change significantly as the Miya community occupies a significant part of electoral discussions. Miya is an honorific term used by Muslims across South Asia, but in Assam, it is employed as a slur to refer to the Bengali-speaking Muslims, most of whom allegedly have Bangladeshi origins and have illegally migrated to Assam.

In the nine parliamentary seats of lower Assam, Bengali Muslims make up the majority in Dhubri, Karimganj and Nagaon, while they constitute about one-third of voters in Barpeta and about one-fourth in Darrang-Udalguri. Voting in these constituencies is scheduled on April 26 and May 7. One of the key differences in the electoral equations in this region is the presence of the regional force—perfume baron and Muslim spiritual leader Badaruddin Ajmal’s All India United Democratic Front (AIUDF).

Assam CM Biswa Sarma had earlier said that he expected a contest only on Dhubri, Nagaon and Karimganj. But later, he stated that he is confident the BJP-AGP alliance will win 13 of 14 seats. The only seat he left out is likely Dhubri, which Ajmal represents.

In these constituencies, Bengali Muslims are hotly debating their choice, trying to figure out the strongest candidate against the BJP.

“Muslims are quite divided as of now,” says Ali Rahman, a resident of Dhing market in Nagaon. “We are discussing it and hope to come to a decision by April 23-24 on whom to vote for. All of us are trying to figure out whether the Congress or the UDF is better posited to defeat the BJP.”

The UDF’s three-time Dhing MLA Aminul Islam is trying his luck against the Congress incumbent, Pradyot Bordoloi, and BJP hopeful, Suresh Bora.

Even the BJP might get a section of Muslim votes in the constituency due to the state government’s development work, says Emran Hussain of Rupohihat, identifying himself as a BJP supporter.

In Darang-Udalgiri, where the Bodo tribal people dominate the demography, the AIUDF has backed the Bodo People’s Front (BPF). This would lead to a triangular contest between the BJP, the BPF and the Congress. Political observers see the BJP in an advantageous situation.

In Silchar of Barak valley, where Bengali Hindus dominate the demography, people consider the BJP as a “clear favourite”.

According to Hafiz Ahmed, a Miya poet and socio-political commentator, Assam’s Muslims are not monolithic, not even the Bengali Muslims. In the past, they have shown different voting patterns and preferences.

“This time, too, the votes of Bengali Muslims will remain divided. In Dhubri, most of them are likely to vote for Ajmal, whereas in Nagaon and Karimganj, the Congress is likely to get the support of the majority of them. In, Barpeta, the CPI(M) is expected to get the backing of the majority of Bengali Muslim voters,” Ahmed told Outlook.

According to political observers, in Karimganj, the Congress candidate Hafiz Rashid Ahmed Chowdhury—a well-known lawyer and human rights activist—has an edge. But in Barpeta, the CPI(M) candidate Manoranjan Talukdar is being considered weightier than the Congress nominee.

Since about six dozen intellectuals had publicly urged the Congress to withdraw its Barpeta candidate, the majority of Muslim voters are likely to favour the CPI(M), which has significant organisational strength in this region. The BJP, however, is confident of its ally, the AGP’s victory from the seat.

Meanwhile Biswa Sarma’s position on Bengali Muslim votes keeps changing. Over the past six months, he repeatedly said that his party did not need or want ‘Miya votes’. But during his campaign for the Darrang-Udalguri candidate, he said that that his government did not discriminate against Muslims. “Developmental projects and beneficiary schemes have been distributed equally to all communities, including Muslims, who I do not think want more than what they have received,” he stressed.

According to author and journalist Rajeev Bhattacharyya, the issues are multifarious, varying from region to region: in eastern and western Assam and also in the Bengali-dominated Barak valley. “The electoral calculus in Assam is dependent to a great extent on the configuration of the population in each of the constituencies,” he says. Bhattacharyya cites the example of the eastern districts, where the mainstream Assamese communities and tea tribes are dominant. The outcome in at least two seats—Jorhat and Dibrugarh—could depend upon which party the tea tribes would vote for. “In the eastern districts, CAA is an issue whereas price rise and unemployment have come into focus in other parts. In western Assam, infiltration from Bangladesh is an issue.”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Snigdhendu Bhattacharya in Assam

This appeared in the print as 'Miya, Axomia And Tea'