As the election clock ticks away in Kashmir, marking the end of the second phase of polling, another timepiece, one familiar in Maharashtra’s terrain, has made an appearance in the Valley.

The timepiece, a rather rudimentary looking alarm clock -- the symbol of the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) headed by Maharashtra deputy Chief Minister Ajit Pawar – has been making its appearance in the union territory’s election paraphernalia, including pamphlets and banners being distributed in Srinagar’s densely populated bylanes of the Anchar neighbourhood of Soura, a notorious hotbed of anti-India sentiment.

Shadib Hanief Khan, the NCP’s candidate from the Hazratbal assembly constituency, distributed pamphlets that contained a beaming image of Ajit Pawar, appealing to residents to vote for him.

The 35-year-old social activist, is one of the 35 contestants fielded by the Ajit Pawar-led outfit in the assembly elections, in what is being construed as the NCP’s bid to earn the formal tag of a national party. More recently, the NCP achieved success in assembly elections in Arunachal Pradesh, securing three MLAs and winning 12 councillor positions in local body elections in Nagaland. It aims to continue this winning streak in upcoming elections in Kashmir.

The Kashmir elections are crucial for both Khan and the NCP. While Khan is aspiring to launch his political career, the NCP is hoping to regain its national party status. A regional party can gain national status by securing six per cent votes in four states or by winning four Lok Sabha seats.

“Everyone in Kashmir knows about Sharad Pawar and his nephew Ajit Pawar. The uncle-nephew parties’ don’t need any introduction,” says Khan, dispelling any doubts about the NCP’s unfamiliarity in the Valley.

In a rapidly altered and potentially evolving political landscape in India post the 2024 Lok Sabha polls, which saw the BJP unable to reach a simple majority, regional political parties appear to be trying to cut a wider swathe. And Ajit Pawar’s NCP is not the only political outfit trying to fish in Kashmir’s electoral pond.

Laloo Prasad Yadav’s Rashtriya Janta Dal (RJD) and Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal (United) both powerful regional parties in Bihar, HD Deve Gowda’s Karnataka-centred Janata Dal (Secular), Mayawati-led Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and Akhilesh Yadav’s Samajwadi Party (SP), both homegrown outfits from Uttar Pradesh and the Revolutionary Socialist

Party headed by Manoj Bhattacharya, are also vying for votes and popularity in the Valley. And in all likelihood, seeking pan-India status.

For the NCP, Kashmir isn’t a new political terrain.

Formed by Sharad Pawar in 1999, it had contested all the state assembly and Lok Sabha elections in the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir until 2014. However, this time, the party is contesting the elections for the first time under the leadership of Ajit Pawar, who became its de facto leader after engineering a split in the NCP in 2023 and wresting the outfit from the patriarch, Sharad Pawar.

Interestingly, the feud, which originated between the uncle and the nephew in Maharashtra, appears to be playing out in bit parts in Kashmir too, with the Sharad Pawar (SP) faction of the NCP offering support to Farookh Abdullah’s National Conference (NC) in the ongoing polls. In Maharashtra, while the nephew’s outfit is in a ruling alliance with the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Shiv Sena (Shinde), the uncle’s NCP faction is in the opposition along with the Congress and Shiv Sena (UBT).

According to NCP (SP) spokesperson Fauzia Khan, Sharad Pawar decided not to field candidates in the ongoing polls in order to avoid splitting its ally’s votes. The party’s district unit would be campaigning for NC candidates and their pitch for restoration of statehood for Kashmir, she said.

For Khan, who had previously contested as an independent candidate in the recent Lok Sabha election, this time he has chosen to go with the NCP, even though the Ajit Pawar-led outfit refused to fund its own candidates and has only offered them support in the form of party name and symbol. “Regional parties look after their benefit. They give tickets to the sons and daughters of their leader, not to common people and youngsters like me who are socially active,” Khan insists.

A relative political newcomer, Khan contesting on NCP ticket, from Hazratbal, is up against two regional giants of Kashmir, the Mehbooba Mufti-led Peoples Democratic Party and the Abdullahs’-led NC.

Until the 1987 assembly elections, when the BJP won two seats, the political landscape in J&K was dominated by the NC and Congress. The 1996 state election, which took place after a gap of a militancy-ridden decade, was one of the earliest instances of non-Kashmiri regional parties like the Janta Dal and BSP participating in elections in the former northern state.

The BSP, incidentally, has a significant base in Jammu’s Samba, Kathua and RS Pura regions -- especially among the local other backward class (OBC) population -- from where the party had won four seats in the 1996 polls. In 2002, the party added another seat to its tally.

Political expert and author, Rao Farman Ali, recalls that these parties aimed to challenge the dominance of the NC, which sought regional autonomy for Jammu and Kashmir.

“They wanted to be an alternative to the NC and INC (Indian National Congress), however, such parties do not get more than two per cent of (total polled) votes,” he says.

This time too, following the abrogation of Article 370, the bifurcation of J&K into two union territories and political assertions about opening up Kashmir to mainstream Indians in more ways than one, the ongoing assembly election has witnessed a surge in participation by non-Kashmiri parties.

Notably, the Congress-led INDIA alliance parties are not unanimous in backing its key alliance partner, the NC, and have fielded their own candidates.

The SP, for instance, buoyed with its unprecedented success in the Lok Sabha elections, which made it the third largest party in the country, has fielded 20 candidates in Kashmir.

“People are looking at the SP with hopeful eyes; they believe in Akhilesh ji because the performance has been fantastic, especially at a time when the BJP spreads messages of hate,” says Dr Aziz Khan, spokesperson and part of the UP-based party’s local team.

SP candidates in Kashmir have had to dismount the ‘cycle’ and plug in a ‘laptop’ as their poll symbol, because the Jammu and Kashmir National Panthers also use a bicycle symbol, aesthetically similar to that of the SP.

“The change of symbol, is no doubt a challenge at the ground level… but people know and look up to Akhilesh ji because he is not communal and wants to take everyone along,” maintains Aziz Khan.

The BSP, which performed abysmally in Uttar Pradesh during the Lok Sabha elections, has fielded 29 candidates in Kashmir this time. Darshan Rana, BSP’s top state leader, said the party aimed to advocate welfare of the OBCs and low castes, comprising 31 percent of the region’s population. The Mayawati-led BSP supported the abrogation of J&K’s special status but is dissatisfied with the non-implementation of central reservation rules in education and employment. Before 2019, J&K's state policy offered eight percent reservation for SC, 10 percent for ST, and two percent for other ‘social castes’, which represent a cluster of weak and under privileged caste groups.

Experts on Kashmir politics suggest that the low voting percentage and general apathy among Kashmiris, mean many are indifferent to the parties entering the political landscape. The lack of high voltage campaigning and absence of influential star campaigners from non-Kashmiri parties could also limit their impact. Independent researcher Mushtaq ul Haq Ahmad Sikandar notes that in this context, these non-

Kashmiri parties primarily aim to “increase their vote share to gain national party status,” instead of wholeheartedly gunning for a win.

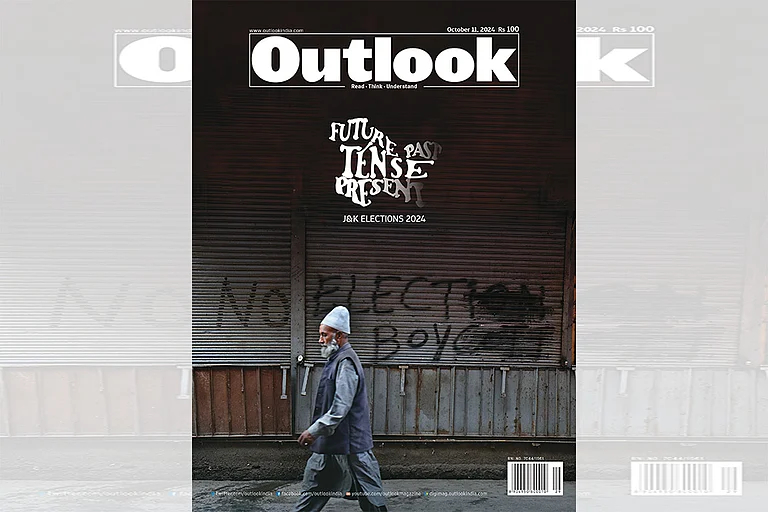

So far, the voter turnout too hasn’t been especially encouraging, even with a host of non-Kashmiri parties adding to the region’s political and electoral colour. The voter turnout in Srinagar remains dismal, with less than 30 percent voters casting their ballot, particularly in pockets like Habbakadal, Soura and Hazratbal, where Shadib Khan has contested.

“Most votes go to main parties like NC and PDP, where voters look for the personalities of the candidates or the party’s ideology. Unless a candidate from a non-Kashmiri party has a strong performance on the ground, there is little chance of them winning. Their nomination is a mere tokenism,” Sikandar adds.