The enveloping silence looks back at you in the form of that blank stare in the eyes of the people you bump into on the streets. It is as if, someone, someday, at some point in time, poured an apothecary’s measure topped with silence into the region’s public water channels. And from the water channels, the silence spread uniformly into the bodies and souls of the people who inhabit the Valley and beyond.

Or perhaps there was a heavy, cold rainfall of silence some time ago, drenching their lips shut. Getting a peek into a Kashmiri mind this election season, is as elusive and frustrating as resolving to climb Mount Everest and then ending up being stranded in a hotel near base camp. Ask anyone just about anything these days and all that one gets in response is a verse or two of Urdu poetry. And it’s no longer words penned by Faiz Ahmad Faiz or Ahmad Faraz. It’s the season for Munir Niazi.

Zinda rahen to kya hai, jo mar jaaen hum to kya

Duniya se khamushi se guzar jaaen hum to kya

(What if we live, so what if we die

What if we leave the world in silence)

This veil of silence in Kashmir has peaked even as the festival of democracy reached its last crescendo.

The silence almost makes you want to give up and run away.

In Kashmir, you would have faced a unique issue once, when everyone was talking. Even minor political events were then viewed through a geostrategic lens, with public appeals often directed to the United Nations Secretary-General. The appeals published in local newspapers before the abrogation of Article 370 are proof of such a time.

Appeals were addressed to no less than the UN Secretary-General and the US President. Now, local newspapers no longer publish such appeals. In fact, no one dares to even appeal to local councillors any more, let alone the UN Secretary-General. However, experts in the police, academia, and journalism still discuss various international issues and their ramifications. Of course, they talk, but off the record. These off-the-record conversations are the essence of any discussion.

“I will talk to you, but off the record,” they say. And once they start talking, they don’t talk about issues confronting Kashmir, but about the consequences of the Russia-Ukraine war on Germany!

When you persist and urge them to comment on Kashmir and recent events playing out in the Valley, the same experts provide various theories and then divert the conversation to faraway places or towards the more convenient (and clever) sanctum of Urdu poetry. Its verses impress most listeners, who often have no clue about their import, thus allowing the speaker to avoid answering the real question.

After the abrogation of Article 370 on August 5, 2019, international theories proliferated in Kashmir. The fall of Kabul further strained the situation, though in the metaphysical realm.

Professor Abdul Gani Bhat, formerly of the Hurriyat Conference, would often say, “Tendas peth tendi tai tendas leaj zeer, Kabul, Kandhar tai bae Kashmir,” an old Kashmiri saying that suggests events in far-off places affect Kashmir.

Post-abrogation, when the theorists disappeared, I sought out Professor Bhat for an interview. I asked him about the arrests of the Abdullahs and the Muftis, including Farooq Abdullah, Omar Abdullah, Mehbooba Mufti and others. He took a long moment, deep in thought, while his admirers watched expectantly. Finally, he said, “War shouldn’t happen between India and Pakistan.” He talked about the catastrophic consequences of such a war, stating that South Asia could not afford it since it would kill millions and lead to devastation.

For a moment, I feared war was imminent. However, upon leaving Professor Bhat’s “war school”, I saw the calm on the streets and convinced myself that war was not on the horizon. Soon after, India and Pakistan signed an agreement to reaffirm the 2003 ceasefire along the Line of Control (LOC).

How did people attain silence in Kashmir, then? It happened gradually.

After the abrogation of Article 370, when the Internet was restored after a prolonged break, people started talking. The Clubhouse was popular and Kashmiris began engaging in discussions. But gradually, everyone fell silent again.

Now, there’s little online discussion beyond wazwan and the beauty of Kashmir. People don’t even criticise Omar Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti. Farooq Abdullah is occasionally trolled, but not for his political views—rather, for his religious sermons.

Dr Abdullah, in his speeches, asks people to offer prayers five times a day, rise early, and pray for the survival of Kashmir. It seems poignant. He says the situation is such that even he fears he might be shot or stabbed for merely being a Muslim. Even the imams of mosques don’t give sermons on these lines these days. Instead, the senior Abdullah appears to have taken over the pulpit. The chief cleric of Kashmir, Mirwaiz Farooq, is not allowed to address people. But it is Dr Abdullah who urges them to pray for the survival of Muslims in current India. He also talks about persuasive silence and occasionally warns that this silence can explode into something unexpected. He is not the only one to issue such cautions.

Understanding this silence, both online and offline, is not easy. Silence has its benefits. Others might feel something significant is brewing, when in reality, nothing is likely to happen.

Silence gives you power when you know you’re powerless and can do nothing. People might attribute your silence to something potent; they think the silence is simmering like lava. They don’t realise it is not a spark anymore, but has transcended into a state of nirvana, where one is content in every state. One doesn’t complain. One just shuts one’s eyes, focuses on the good things and moves on. They must understand this by now. They shouldn’t be worried about someone’s silence or give it undue geostrategic importance.

If a road is bad, talk about a good road elsewhere. One doesn’t complain about power cuts, one speaks of the restoration of power. One doesn’t complain about the lack of facilities in hospitals. Instead, one talks about the facilities that exist. On the record, there is a tsunami of positive thinking.

When some officials compare Kashmir to Switzerland and say it is even more beautiful. And many of us respond, “Wah kya baat hai (well said), you are right, sir.”

We have no alternative but to feel like we are enjoying Switzerland while in Kashmir. To visit Switzerland, you still need a passport. When officials say Kashmir is Switzerland, perhaps they are in Switzerland, which is why the comparison. Since passports are hard to come by these days, why not get the feel of Switzerland in Srinagar? This mindset has significantly contributed to the physical and mental well-being of Kashmir.

I recently asked an elderly person in Pahalgam about the issues in Kashmir, and he looked at me with surprise. “What will you do if I tell you about the problems and issues?” he asked. “I will write about it,” I replied. “So what? Who reads these days?” he said. I didn’t give up. “Yes, no one reads. But you can give me a video interview,” I suggested.

“Why should I? Even if I count all the problems, nothing is going to happen. It is better to be silent. These days, silence is better,” he said. I persisted. “Why is silence better?” “Because there is nothing to talk about. Besides, we are too tired of talking,” he said and then walked towards the polling station across the stream.

After he cast his vote, I saw him sitting near the stream, talking to his local acquaintances. And they were talking. It is not that people aren’t talking. They are, but they don’t want anyone to hear what they are talking about. They want to keep to themselves. They have had enough of talking outside their circles. It is time to be silent beyond their sphere of comfort.

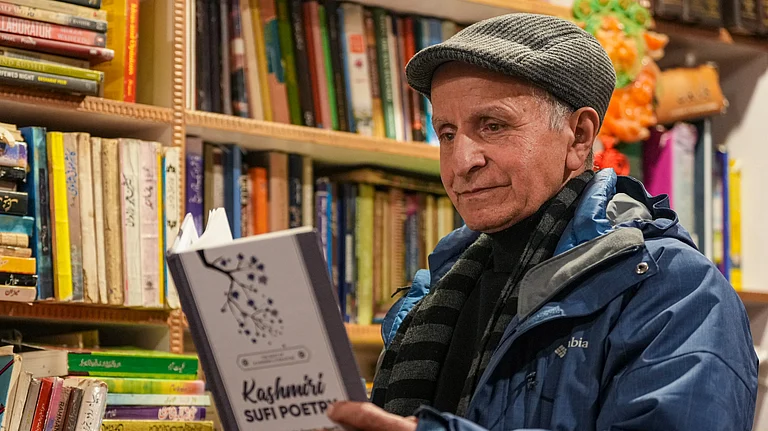

The silence seems like a collective decision, as if people have witnessed something significant and have taken a collective vow in the Sufi tradition to remain silent, to those outside their circle of familiarity. They don’t want you to enter that circle. If you do, you won’t hear anything because they don’t talk.

I asked a young man in Bijbehara how he interprets this silence. He said, “It is a Kashmiri thing, you won’t understand.” “I am Kashmiri,” I replied firmly in Kashmiri. He laughed and said, “You know it well.” The conversation ended there. People do talk—on shop fronts, in friend circles, at wazwan and at private parties. But they don’t let outsiders listen in. They no longer talk in WhatsApp groups. Those groups are dead now.

In Baramulla, I recently approached a young man with a simple question: what would he do if elected as an MP? His response was striking. “I will talk only about azadi,” he asserted, looking me in the eye. Intrigued, I accepted his challenge to interview him on azadi.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

As the camera rolled, he proclaimed his unwavering support for azadi. When pressed to elaborate, he said, “Employment ki azadi, jobs ki azadi, good roads ki azadi,” before abruptly retreating to his friends amidst laughter. Their conversation remained a mystery to me.

(This appeared in the print as 'Talking Of Russia-Ukraine')