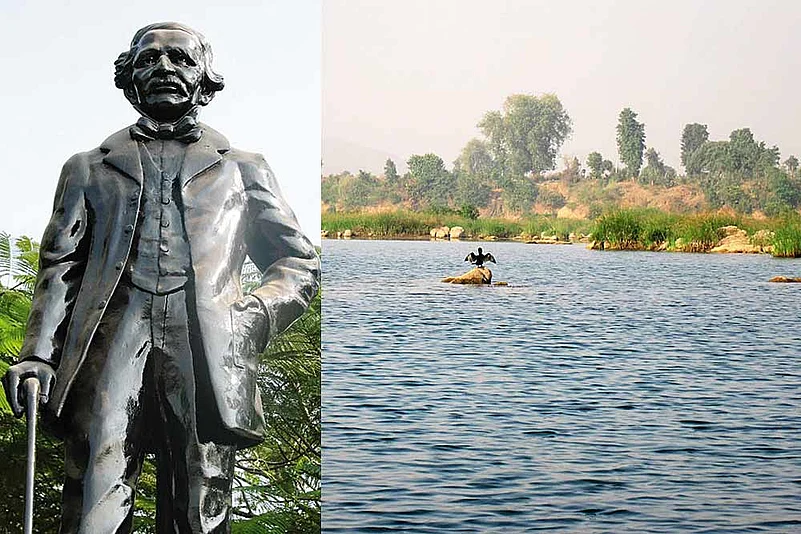

Over 160 years ago, a British, who regularly tussled with his superiors, and others, visualised a grandiose project, one that is taking a concrete shape in the twenty-first century. Sir Arthur Cotton, who worked in the Madras Presidency during the Raj period, was passionate about irrigation and waterways. His critics said that his head was full of water, which, according to them, explained his crazy ideas. For his admirers, largely Indians, he was Lord and King. Some of the plaques on the thousands of his statues that line the River Godavari’s coast in South India read ‘Apara Bhageeratha’ (the divine king who brought down the River Ganga to Earth) and ‘Cotton Dora’ (Lord Cotton).

It was Sir Cotton, who build the dams that converted the Godavari region, and Andhra Pradesh, into the country’s rice bowl. It was Sir Cotton, who first envisaged the linking of the various rivers in the north and south India. His vision, “What is wanted is the connection of the various irrigations, so as to complete steamboat communication from Ludhiana, by the Sutlej, Jumna (Yamuna), Sone, Ganges, Mahanaudi (Mahanadi), Godavari, Kistna boat canals, and one from Nellore through the Carnatic to Ponany, so as to bring produce to a point opposite to Aden at an almost nominal cost. That’s the grand object.” Hence, his river-linking scheme envisaged both irrigation and cheaper transport through waterways. And it was because of his opposition to the Raj’s railways.

Only in 1980 did the ministry of irrigation finalise its National Perspective Plan. It identified 30 river links — 14 Himalayan components, and the rest Peninsular ones — to “transfer water from water-surplus basins to water-deficit basins”. This was to address the problems of floods and drought, irrigation and power production, apart from the acute water shortage. By 2025, the per capita availability of water is expected to slump to 25% of the figure in 1950. In recent times, the pace has quickened. According to government estimates, the project will “give benefits of 35 million hectares of irrigation, raising the ultimate irrigation potential from 140 million hectares to 175 million hectares, and generation of 34,000 MW of hydropower”.

Of the 16 ‘Peninsular’ components, the feasibility reports for 11 are complete, detailed project reports of three are ready, and two are in the pre-feasibility report stage. In the case of 14 ‘Himalayan’ components, the draft or final feasibility reports are ready for nine projects, four are in the pre-feasibility report stage, and one, which was an alternate link, was dropped. Clearly, the linking of the Indian rivers is a gigantic project. Just to give an example, the combined cost of the four ‘Peninsular’ components, whose detailed reports are complete, is almost Rs 40,000 crore. A decade ago, the cost of the 30 links (actually 29, since one is an alternate component) was estimated at between Rs 4.5-5.5 lakh crore.

According to media reports, the two phases of the Ken-Betwa project in the states of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh are touted as “model” project “for its extreme attention to detail on environment management”. The environmental plan for the Phase 1 is over 1,000 pages. Officials claim that the project is feasible, practical, and beneficial. They point to the other countries, which have successfully linked their water sources. For instance, the US and China have successfully completed mega projects that transfer huge quantities of water. China’s South-North Water-Diversion Project has three links — eastern, central, and western — of which the first two are completed, and carry a combined 19.5 billion cu m of water. Even neighbouring Pakistan built 10 links to join all its rivers within a decade (1960-70).

But there are critics and detractors of the river-linking project in India. Some talk about the “uncertainties with water logging, salinisation, and the resulting desertification in the command areas”. There are concerns about “sediment management”, as it will entail changes, and perhaps losses, in the ecosystems. As one article says, “The apprehension of rivers changing their courses remain — there is no clear formula to address this in context of the Himalayan system…. Other fears include trans-boundary water conflicts.” Bangladesh has opposed the Manas-Sankosh-Teesta-Ganga link. It claims that the link can potentially destroy the irrigated paddy fields in eastern Bangladesh.