There is no doubt that the illegal wildlife trade is huge, about $8-10 billion a year (including fish and timber). But more importantly, it is now evident that it is transnational in nature, with links to organised crime and terrorism. The local poaching is planned on a global scale with linkages to the logistics and distribution businesses. This is evident from the illicit trade in ivory and horns — from Africa to Asia. First, look at the sheer scale of the trade. There are over 118,00 less elephants in Africa compared to a decade ago. Experts contend that this was “largely due to poaching”. The number of dead carcasses per 100 is the highest in illegal trade nations of Mozambique (32) and Tanzania (26), compared to Uganda (0.5) and Zimbabwe (8). The first two have lost 50% and 60%, respectively, of their elephants.

It is the same with the rhinos. Over 6,000 were illegally killed in the past decade. Although the number is not as scary as that of the elephants, it needs to be remembered that their overall numbers “are very low, with less than 30,000 rhinos of any species left in the world”. Hence, “the illegal trade poses a very real threat to the survival of the species”. South Africa is the home to 79% of the world’s population, and “at least one quarter of which are privately owned”. At the peak, the rhino horns, just like the elephant ivory, sold at huge prices in Asia with high profit margins. Hence, the poachers used violence, when necessary.

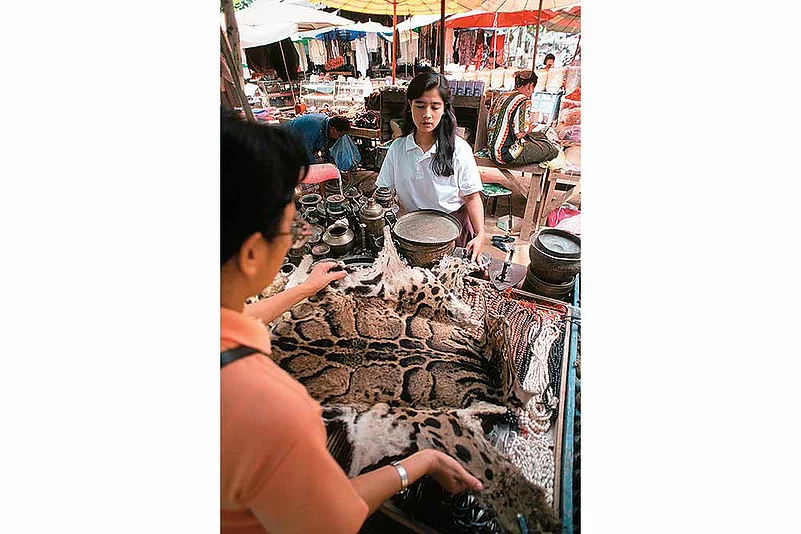

For both the ivory and horns, the main consumption countries are China and Vietnam. Data between 2006 and 2015 indicated that 70% of the illegal horns were sold in these two nations. In the case of ivory, “China was the largest national destination of detected ivory shipments between 2006 and 2015”. However, what is crucial is that in several cases of detection and raids, investigators found “mixed species loads”. This implied that the horns or ivory were mixed with other poached animals, which hinted that all these trades were handled by a centralised entity. Such a level of organisation is found in mafia and drug cartels.

In recent cases, poachers shifted from high-risk areas. According to a UN report, “South Africa has seen a reduction in the number of detected killings over the last two years. While this is undeniably good news, the location of these killings has shifted in ways that give rise to concerns. In 2016, poaching declined by almost 20% in Kruger National Park, but increased by 38% at various reserves in Kwa-Zulu Natal. This shift suggests a tactical move on the part of rhino traffickers in response to enforcement efforts.” But it also suggests the involvement of transnational organised crime groups.