Towards the lighter last leg of certain Carnatic vocal concerts would pop up a composition that will have no lyrics. Even if the kacheri is instrumental, the curious slant of the notes will prompt the first-time listener to wonder what the whole avalanche of sounds is about.

Well, doesn’t it come close to Sankarabharanam? Or is it that raga itself, rendered in a form devoid of Dravidian oscillations that takes it to the realm of Western classical where the

scale is called C-Major?

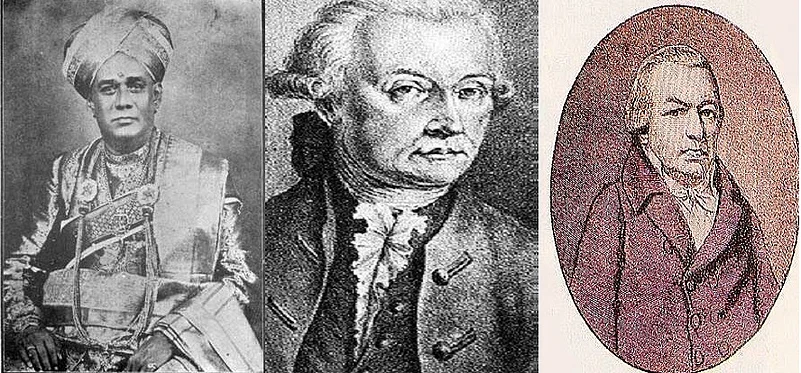

Ah, for someone largely unfamiliar with south Indian music, these are perhaps immaterial. What bowls him/her over, most likely, is the jovial mood the piece evokes. The short item is widely acknowledged to have been composed by Harikesanallur Muthaiah Bhagavatar(1877-1945). The musician was born in a village close to Tirunelveli deep south of what is today the state of Tamil Nadu.

If the Agasthyarkoodam stretch of the Western Ghats made Tirunelveli rain-shadow by blocking the annual entry of southwest monsoons, the region also can neither boast of a special European connection even during the Raj-era India. Hence the British rule doesn’t lend itself to be a reason why a musician from that locality composed ‘English Notes’. In any case, Carnatic classical had, decades before the Bhagavatar’s creativity bloomed, felt the influence of Western music. Some of the ‘Nottuswara’ compositions of the famed Carnatic trinity’s Muthuswamy Dikshitar (1775-1835) are celebrated for their adaptation of the south Indian system. Studies say such simple Dikshitar melodies were inspired by Scottish and Irish tunes, thus marking early traces of an East-West blend in world music. They do have lyrics, typically praising Hindu gods. Here is an example — Rama Janardana:

The story may have begun there, but it least ends with it. In any case, Muthuswamy’s younger brother Baluswamy Dikshitar (1786-1858) is widely accounted to be the mind and hands that introduced the violin to Carnatic music. The string-and- bow instrument subsequently underwent a lot of improvisations that eventually made it sound largely south Indian—to the extent that the violin has for long now been capable of solo kacheris besides its accompanist status.

Back to Muthaiah Bhagavatar, how and why did he compose such a number that is a big hit even in 2017? One story, perhaps just legendary, goes thus: he was challenged by an Englishman to compose a music based on Carnatic genre that has a Western influence. Music enthusiast Srilaya Nataraj, who is among those who states so, adds the obvious in his blog the more obvious: the item was popularised in kacheri circuits by the Bhagavatar’s top disciple Madurai Mani Iyer (1912-68).

Cultural scholar Krish Ashok says the item showcases the Bhagavatar’s self-teaching talent in expanding beyond one’s classical training. “This piece was extremely popular with an Independence-era audience that felt pride in one of their own ‘getting’ western music, while no English man could perform a Thodi alapana,” he notes in his blog. “It will be great if more talented musicians take this melody and set it to even better background scores.” In more recent times, the composition is used in various ways, sometimes even with background scores that give it a film-music mood. After all, a Western piece, however minutely notated, does not stop the Indian musician to experiment with it in countless ways. The below record, by vocalist Nithyasree Mahadevan is only one among the many such

instances.

As for the Sangita Kalanidhi Bhagavatar, who was first principal of the 1939-founded Swati Tirunal Academy of music started at Thiruvananthapuram almost laterally west of Harikesanallur, he composed almost 400 musical forms, the largest among the post-Trinity composers.

Just for the record here, two European composers were born on November 14. Johaan georg Leopold Mozart (1719–87) was a German composer, conductor, teacher and violinist, while his compatriot contemporary Johann van Beethoven (1740-92) was also a teacher and singer (at the chapel of the Archbishop of Cologne).