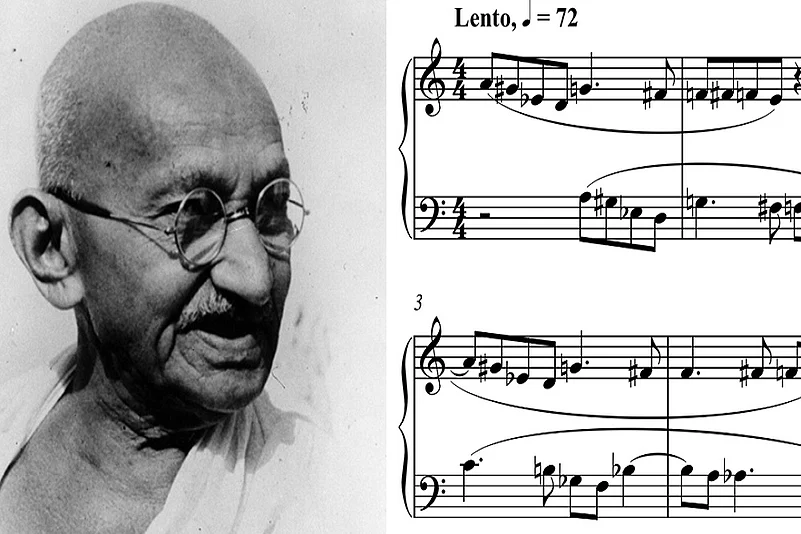

In one of his famed trips to Europe, Mahatma Gandhi happened to listen to Western classical music. That was in 1931, when the apostle of non-violence visited Switzerland.

In the serene Alpine country, the Indian dignitary sat meditatively to hear an orchestral masterpiece. French writer-historian Romain Rolland, as Gandhi’s host on the occasion, recalls that experience with disarming candidness.

In a letter, he wrote to an American friend thus: “On the last evening, after the prayers, Gandhi asked me to play him a little” of influential German composer-pianist Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827). From there, it’s within brackets that Rolland writes a sentence: “(He does not know Beethoven, but he knows that Beethoven has been the intermediary between Mira and me, and consequently between Mira and himself, and that, in the final count, it is to Beethoven that the gratitude of us all must go.)” By Mira, Rolland, who is also a Gandhi biographer, means the aristocratic British woman Madaleine Slade who lived and worked with the Mahatma. “I played him the Andante of the Fifth Symphony. To that I added “Les

Champs Elysées” of Gluck—the page for the orchestra and the air for the flute.”

Back in his own country, Gandhi largely used to listen to bhajans, going by notes about the Father of the Nation. It is evident that he had a particular fondness for certain bhajans, some of which went on to be so popular (even today) primarily because of their association with the Mahatma. (So much so, a few of them have more of implied patriotism than the originally-conceived devotion to god.)

Which can lead us to a curious bit of thought: How much of musicality did Gandhi have as someone obsessed with altruism and busy with socio-political activities? Apparently, there are no many instances of anyone having gauged it in depth—beyond inferring that music was to him part of spirituality, which was also an obsession of the Mahatma.

For instance, Hari Tuma Haro was one invocatory song Gandhi especially preferred to hear. More so from the famed vocalist M.S. Subbulakshmi. “Her voice is exceedingly sweet,” Gandhi was later quoted (by fellow freedom fighter Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel) as saying. “To sing a bhajan is one thing; to sing it by losing oneself in god is quite different.” It was in 1947, close to his 78th birthday, that the Mahatma got young Subbulakshmi to sing the bhajan (about which her husband, Kalki editor T. Sadasivam, had initial reservation because she knew neither its lyrics nor the tune). As the musician was in no position to meet Gandhi in Delhi, she recited the 15th-century Mira bhajan to be recorded in a tape—and the spool was sent to the capital city upcountry.

Hardly four months later, when the Mahatma was assassinated on January 30, 1948, Akashvani went on to play several times the Subbulakshmi rendition. The Carnatic musician from Tamil Nadu had, incidentally, sung the verses in Darbari Kanada, which is primarily a Hindustani raga associated with his ethos of pleasing the king in the court.

Another well-known ‘Bapu bhajan’ is Vaishnava jana to. This is, again, a 15th-century poem, but penned in Gujarati, which is Porbandar-born Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s mother tongue. Written by Vaishnav devotee Narsinh Mehta (1414-81), it speaks about the ideals, routine and mindset of a Vishnu devotee.

As for the raga, the song is generally tuned to Khamaj of the north Indian classical stream. The raga does have its counterpart in the south, where it is called Kamas, and is a much smaller melody-type (with Hari Kamboji as the parent scale) rarely taken up as the main item in a concert.

If one were to go for a survey of sorts, one bhajan massively associated with Bapu should be Raghupati Raghava Raja Ram. Extracted from the Hindu text Nama Ramayanam that is a seven-chapter version of the Valmiki epic condensed into 108 shlokas, this song carries the famed lines Ishwar Alla tero naam, Sabko sanmati de bhagwan, clearly spelling out a vision of secularism in its modern sense of gods of all faith being the same though known by just different names—and that a ‘good mind’ is what the human kind essentially requires any time.

The raga, if its exploration is a compulsion, isn’t all too clear in this song. It is largely a shade of Hindustani Kaafi, known in the country’s peninsula as Kaapi. Like subtle variations that is a feature of other ‘Bapu bhajans’, Raghupati Raghava is also heard in slightly different tunes, sometimes closer to Dwijavanti (or Jaijaiwanti of the north).

No such dissection calls for a conclusion that the charm of the classical ragas was what wooed Gandhiji to such bhajans (with the above list being incomplete). The proponent of peace did famously go (more than once) to eastern India’s Santiniketan, founded by Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, who had named him the Mahatma. The two first met in 1915 at the institution in Bolpur off Birbhum. Much later, in 1940, a year before the iconic litterateur’s death, Gandhi was taken around the Santiniketan campus, celebrated for its teaching in various forms of Indian arts—performing or otherwise. The Mahatma was later known to have said that he sensed an “overdose of music and dance” in the place.

Back to his younger days, Gandhi as a student of law in London in his twenties, did try his best to get a more direct taste of music. “He bought a violin and took lessons in music,” writes Donn Byrne in his 1984 book Mahatma Gandhi: The Man and His Message. “He even tried to how to dance, but he had no sense of rhythm and soon gave up his lessons.”