The unhurried pace in the opening phrases of her sonorous rendition defined the key characters of the vocalist’s style called Bhendibazaar, though the word may naturally appeal

as something chaotic to those unfamiliar with Hindustani classical.

What’s more, the thesis that had won Suhasini Koratkar a PhD was titled ‘Spiritual Importance of Indian Music’. The Pune-based vidushi passed away on Tuesday night (November 7) at the age of 73.

Her death, connoisseurs note, marks yet another major loss to a north Indian music school with a chequered antiquity of one-and- a-half centuries. Bhendibazaar, sometimes confused with a marketplace for the vegetable bhindi (ladies’ finger), is a south Mumbai pocket believed to have gained its name as a corruption of the colonial-era ‘Behind the Bazaar’ (as families of the ruling British resided south of Crawford Market in Fort area).

That apart it has been a cultural hub, having given birth and nurtured one of Hindustani music’s distinct streams.

Dr Koratkar comes in the 4th generation of the gharana that has its origins in 1870 when three musician-brothers from the Gangetic plains upcountry moved to Bombay.

It was to learn the meditative Dhrupad genre that Chajju Khan, Nazir Khan and Khadim Hussain Khan from Moradabad settled in Bhendibazaar. The extremely slow speed of Dhrupad the trio trained under Dagar-baani ustad Inayat Khan did have a lasting bearing on their khayal as well, thus sowing the seeds of a new Hindustani gharana around the crowded but prosperous urban space the siblings (originally trained in the Rampur-Sahaswan gharana)

made their home.

Chajju Khan’s son Aman Ali (1888-1953) later emerged as one of the brightest torch-bearers

of the Bhendibazaar style, which also began borrowing the aesthetics of Carnatic music.

It was Aman Ali Khan who, for instance, introduced popular south Indian raga Hamsadhwani into the Hindustani. Dr Koratkar used to be particularly fond of its rendition, acknowledging her indebtedness to both the Deccani system and the eclectic ustad in the process.

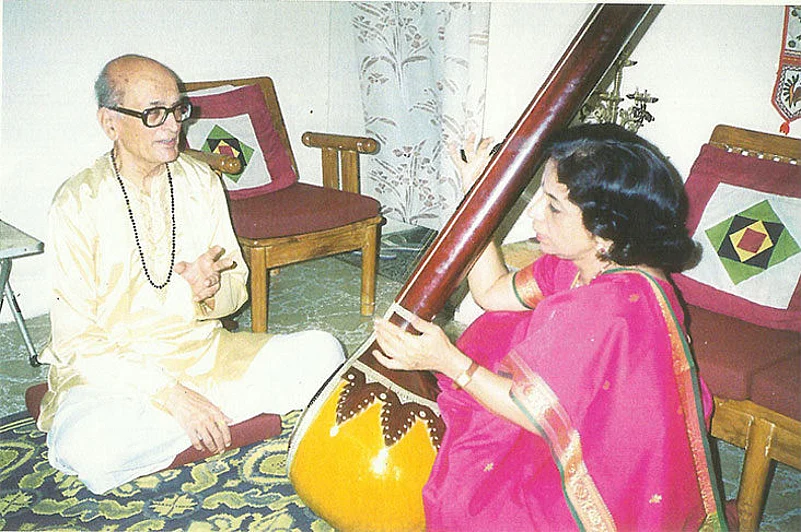

If the Bhendibazaar style is noted for its forceful gamakas (oscillations) while going for the taans featuring rapid melodic passages using the ‘aa’ sound, it has possibly something to do with the Carnatic influence. This can, again, be a reason why this Hindustani school has patterned passages of sargam (where swaras are delivered in a sequence) rather than going for freewheeling shuffle of the notes. All of it was safe in the presentation of Dr Koratkar, who was trained in khayal by the renowned T.D. Janorikar (an Aman Ali disciple, who died in 2006 at age 84) and in semi-classical by thumri exponent Naina Devi (1917-93).

Dr Koratkar, who was an expert also in less-weighty ghazals, bhajans, abhang, Marathi natyageet, dadra, hori and kajari, did get an opportunity to get exposed to various kinds of music in her senior role in All India Radio, where she became a programme executive with its Pune station in 1975. A decade later, she was posted at the Akashvani’s Delhi headquarters, working as the director of programmes (music). That stint gave her a good command in charting out the artistes for the annual Akashvani Sangeet Sammelan, overseeing audition tests and having a big say on broadcast music. The latter half of the 1980s saw her organising Bhendibazaar Gharana music festivals in Delhi as well as Mumbai.

This bright phase of her life was a far cry from a critical period Dr Koratkar went through in her younger days—though she had by then got her doctorate in 1970. The vocalist fell victim to poor health that manifested as incessant cough and frequent bouts of cold. An Ayurvedic expert she consulted told the musician that her lungs had gone extremely weak and singing

something as powerful as Hindustani vocal could be next to impossible.

Her main guru, Pt Janorikar, took up this as a challenge and began giving special music training to a sad Suhasini. He taught her yoga, pranayam and omkar sadhana—all of that began showing promising results after a few years. Throughout her career, Dr Koratkar continued her breathing lessons, which scholars note lent a serene quality to her music.

Complementing the trait, the artiste (who had graduated in Economics) ensured that her disciples too had a grip on both theory and practice of music.

A transfer to Goa AIR after a successful stint in Delhi prompted Dr Koratkar to think more about the need of documenting her gharana—its history, key characteristics, masters and possible future. She quit the job and returned to Pune, where she resumed tutelage under guru Janorikar. Her Mission Bhendibazaar Gharana involved recording of the music, interviews with its masters, collection of old discs and holding lecture-demonstrations, besides writing for journals and souvenirs. The Sangeet magazine’s special issue in 2006 (the year which Pt Janorikar died) was on Bhendibazaar gharana, with a chunk of it carrying the writings of Dr Koratkar. The art world hails the whole exercise as a historic effort to revive a fading gharana.

Now that Dr Koratkar is no more, her school of Hindustani music will miss a major pillar. But, as is the case with most gharanas, a younger lot of practitioners enrich their school with new

ideas and influences—in continued spirit of the generations.