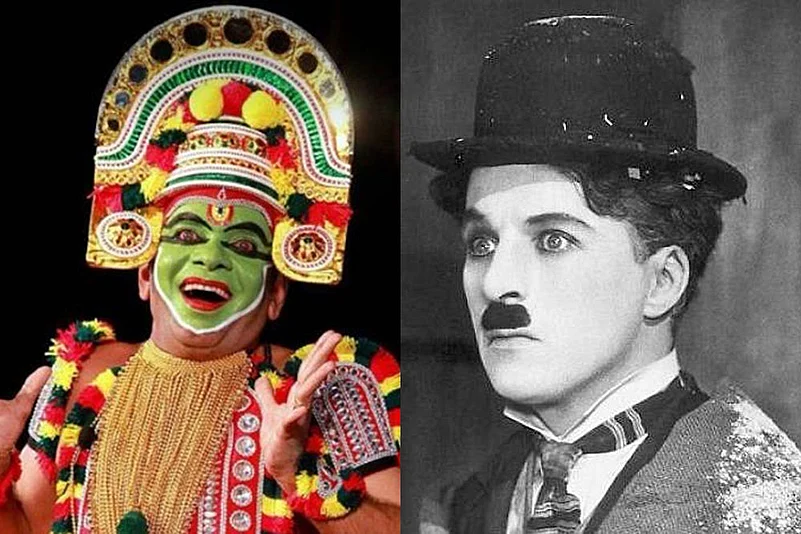

Kunchan Nambiar wasn’t exactly Kerala’s Charlie Chaplin though both geniuses did display exemplary skills in humour through the art-form they excelled in their lifetime. For one, the Malayalam poet had died 12 decades before the Western filmmaker was even born in 1889. By that logic, people in God’s Own Country should only be calling Chaplin America’s Kunchan in case they sensed parallels in their genre of comedy flavoured with satire.

If Kunchan has never gained the kind of global fame London-born Chaplin (legitimately) enjoys, the reason is obviously linguistic. The writer revelled in a language that is still intelligible only to people totalling at best 3.5 crore—a numerical expression that warrants expression as 35 million for the non-Indian to make sense. Chaplin, on the contrary, relied least or just marginally on literature in his (silent) films, which conveyed immensely through pure action edited together to form hilarious plots steeped in amazing symbolism.

Kunchan (1705-70), too, didn’t actually limit his artwork to writing. In fact, the litterateur conceived every word he penned as material for physical expression in a performing art he founded—overnight, going by an apocryphal story. Thus was born the folksy Thullal, a one-man act featuring hand gestures, footsteps, facial emotions and rudimentary dance (though to sometimes complicated rhythms). The performer in stylised make-up and costume would himself (of late, also herself) sing the Kunchan lyrics, which the accompanist musician—seated on the side of the stage and chiming small cymbals held on both hands—would repeat sufficiently for the acting part to get over. All these, to the accompaniment of a couple of percussion instruments: the ethnic mridangam and edakka these days.

If self-deprecating jokes and gallows humour formed highlights of what the world cinema celebrates as Chaplinesque from the days of Charlie (1889-1977), then Malayalis had got an on-stage taste of it from the time of Kunchan himself. Hindu mythology was the focal theme of the poet’s large body of works, yet fun-filled social criticism would come up as the tacit target. In a way, Thullal virtually used Purana characters as an excuse to rip open the various maladies in contemporary human life and expose them without sounding to be preachy. Never lost is the clownish quality of the Thullal performer on stage.

In that context, the death of a Thullal exponent on stage this week has given a mind-boggling extension to the subtle philosophy of Kunchan himself. Amid colourful festivities at a central-Kerala temple, Kalamandalam Geethanandan, only 58 and always agile, collapsed on the dais. Cardiac arrest killed one of the most popular Thullal practitioners who had successfully retained the art-form’s classicism, seldom seeking to make it look compromisingly cheap.

The January 28 tragedy happened past dusk when a chirpy crowd at the Avittathur shrine was watching Kalyana Sougandhikam in the most common of the three forms of Thullal: Ottan. The presiding deity at the religious abode in Thrissur district is Mahadeva. Now, that’s simply another name for Shiva, who is the lord of destroyer for the Hindus.

(The only performer who Kerala saw breath his last on stage in recent history was Keralanadanam maestro Guru Gopinath—at a Kochi auditorium in October 1987. The anklets met with a sudden silence when the dancer enacting the role of King Dasaratha of the Ramayana on the 9th of that balmy month by the Arabian Sea was aged 79.)

Back to Thullal, if it’s Ottan, then the performer paints his face with green (unlike yellow for Seethankan and near-to-nothing make-up for the third variety called Parayan). Geethanandan, typically, had his face brightened in a hue that looked like that of tender leaves of a temple banyan tree—almost symbolising his own youthful resilience in middle age after an angioplasty half a decade ago. Even as the body lay motionless, the visage looked like he was still ready to perform.

The parting lines of Geethanandan were, again, laced with black humour. It was on a robustly-built Pandava prince who was set to gain even more strength. The tall and wide Bhima is anyway central to the play he was enacting, though it is equally striking that the same Mahabharata character was to meet his elder brother Hanuman for the first time ever (in the woods that were as green as the Ottan Thullal artiste’s face).

The village of Avittathur is close to Irinjalakuda, where Kunchan had a close pal in another writer of high stature. Unnayi Warrier, who lived sometime between 1682 and 1759 was a Sanskrit scholar and astrologer best known for his contribution to Kathakali. Warrier’s Nalacharitham continues to be a much-staged story-play till date in the state’s classical dance-drama. Kerala’s lore has several entertaining nuggets comprising interesting meetings, which include intelligent wordplay, between the two Kunchan and Unnayi.

Geethanandan, who was born into a poor family in Akilanam village south of Pattambi off Palakkad which is the district that spots the house of Kunchan in riverside Killikurissimangalam, often used to lace his conversations with wit. He was trained in Thullal at the state’s premier performing-art institute of Kalamandalam after primary lessons in the art from his father Kesavan Nambisan. His alma mater absorbed Geethanandan as a teacher in the Thullal department, from where he retired last summer as the head. Earning a legion of disciples from Kerala’s northern end to down south apart, the artiste was very much a busy performer—and had presented the Thullal abroad (Eruope and West Asia) as well.

In his last moments, a video of which is being widely circulated on social media to the high excitement of many and deep sorrow of others, Geethanandan doesn’t fall like a comedian. Apparently feeling uneasy around his chest, he moves to the right where his accompanists are seated in a row. So graceful are the steps even at that closing time that the vocalist mistakes the act for a new trick from the artiste, who then kneels down in reverence—as if guilty of orphaning them midway the show. It’s only when his face strikes the bare floor that a streak of chill enters everybody—including the audience.

That last act of this performer will ever puzzle even Kunchan and Chaplin.