A little over four years ago, Kota Neelima paid yet another visit to Ayodhya as an author-journalist. This time, though, a curious thought overpowered the Delhiite at the eastern Uttar Pradesh city that has for long been mired in a religiopolitical feud.

“What will occupy the space left behind by the removal of a place of worship,” she wondered at the site that Hindus believe is the birthplace of Lord Ram, but a temple in his name was reportedly replaced by a Mughal invader five centuries ago—only to be pulled down in end-1992, heightening an inter-community property dispute that remains unsettled till date. “Will the space still serve as a spiritual point of reference?”

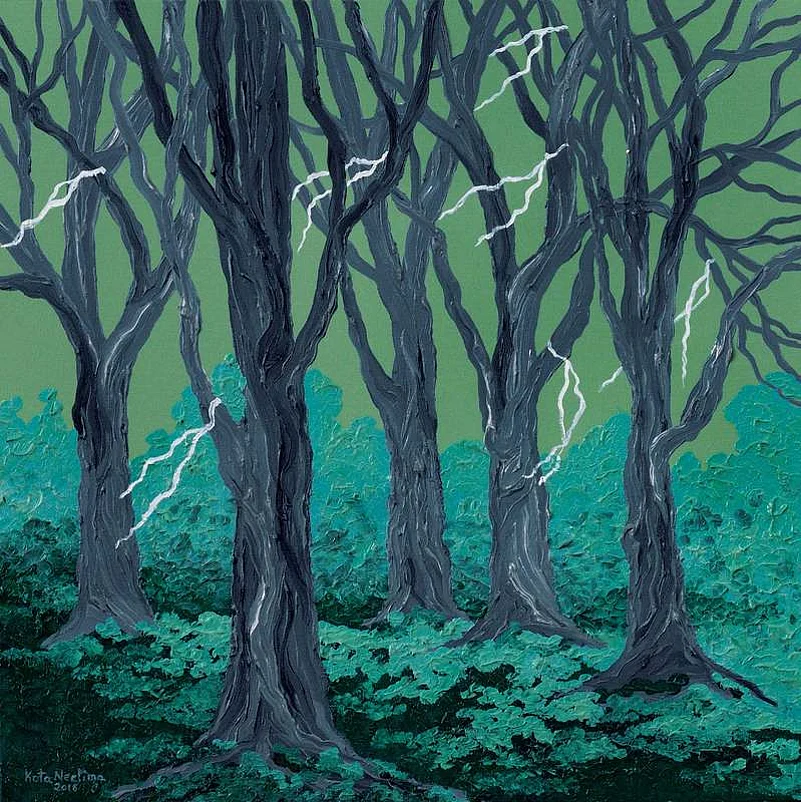

The questions arose because Neelima had by then began thinking if shrines were restricting one’s natural quest to be spiritual; whether a temple or mosque was tending to block the essential trip to explore the inner self. The thoughts lingered for months after the trained artist got back to the national capital—so much so, a year later, she sought to paint the visual of half-a-dozen trees in a forested land. It’s title: Prayers.

The oil-on-canvas work underwent an array of modifications over the next three years in her studio at Jangpura Extension in the city’s south. More importantly, it became the starting point of a series of artworks under a holding theme: elevation of every tradition to its core meaning. Virtually, the whole of 2016 was spent meditating over the visual subtleties of the labyrinthine thoughts, which continued till the artist reached a point where she realised the process was poised for a natural end if not a break.

Neelima ended up doing 23 paintings—almost all of which apparently portray serene nature, often in colourful bloom. Then, as a reminder to their genesis, she titled them ‘Remains of Ayodhya: Places of Worship’. To her, the town off Faizabad today is “an absent place of worship” even as it “may now be a spiritual point of reference”.

“That initial work in this series didn’t first have the prayer flags to the trees,” she recalls, sitting at Delhi’s Alliance Francaise in the quiet Lodhi area, where a basement gallery is holding Neelima’s latest works’ exhibition in coordination with capital-based Culture Collective that works for increased public access to art. “Oil has always been my preferred medium. Only, this time I have gone for canvases that are smaller than usual.”

Interestingly, the impressionist-abstract artist has a rather strange prelude to each of her work with the brush. She would write down the ideas behind each of them. “Often they are long notes. Would run into 10 to 12 pages,” adds 45-year-old Neelima, who has studied painting techniques at Arpana Caur’s Academy of Fine Art and Literature and is an author of four bestselling novels on poverty and political corruption. “All the same, language should not control your thoughts; instead must brighten up your spiritual side.”

Standing out with images that goes with the general grain of the show is a work titled ‘Talking Stones’. The 24x36-inch painting takes a zoomed-out view at a landscape defined by rocks, which Neelima notices are typically “sculpted by water or winds”. “It’s a congregation of stones in tranquility, talking to each other or to us or both.”

Neelima’s show, which is on till January 16, has a segment under ‘The Moon’, where the surreal quotient particularly thickens. One has the celestial body seen in a sky that is brown of all colours amid a cluster of clouds that seem to find bluish reflections below, where a lone leafless tree pops up a white-lined silhouette and leaves it to the viewer to assess—if at all—whether it’s anchored on earth or floating in the air. “A pair of young visitors just told me the image reminded them of bedtime stories,” adds the artist, who has family moorings in paddy-rich Krishna district’s Kota village of Andhra Pradesh.

Overall, Neelima, who made a relatively late entry into public domain as an artist by putting up her first show only in 2005, believes her ‘Places of Worship’ seeks to free Ayodhya from its perceived boundaries and find it the way it has been: without form that belonged to any one religion and without tradition allied to a particular faith. “Seeking for god can be not just for yourself, but for the whole humanity.”