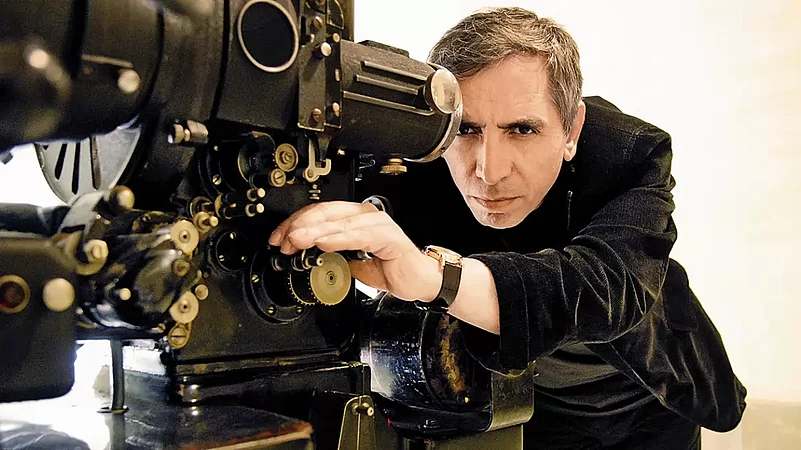

World-renowned Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf says the demonstrations in Iran are a cry by women to live life on their own terms, to have the right to fall in love and to own their bodies and their expression. The filmmaker changed the language of global films through renowned works like A Moment of Innocence, Time of Love and Kandahar, among others. In a conversation with Abhik Bhattacharya, the filmmaker hopes a new Iran will soon emerge where democracy will write history, not dictatorships.

You are among those filmmakers who have changed the journey of Iranian films. In what ways do you think films can change political discourse?

After the 1979 revolution in Iran, government narratives were nothing but religious propaganda and political lies. I spoke in my films against this hegemony, about social realities and the dream of freedom, especially the freedom of women. For example, I made the movie, Time of Love where I defended the right of women to fall in love outside of religious laws. My wife (Marziyeh Meshkini) made The day I Became a Woman that showed how a 9-year-old girl is forced to wear a headscarf due to religious norms. My daughter Samira made The Apple which tells the symbolic story of a father who imprisons his daughters at home because of his religious beliefs to please the God of the mullahs (priests).

What is reverberating in the streets of Tehran now, the right to freedom in lifestyle, is not a new demand. This dream has been there for the last 44 years in Iranian films against the official narrative of Iranian governments.

From a sociological point of view, counter narratives against the hegemonic one usually start from one person or a small group. Then, it turns into the narrative of the majority. Of course, sometimes a generation is needed to speak up. One can understand the narrative of the society from its artists. If you look at the movies made in Iran’s art cinema from 1985 to 2005, you can clearly see the dream of those who died for the rights of women, right to life and freedom in the streets of Iran today.

From A Moment of Innocence (1997) to The President (2014), one can detect a ‘rebel with the essence of love’. Where does this rebellion come from?

In Iran, when a child is born, the mullahs recite the azan (call for prayer) in his ear to say: “O child, be careful! You entered life under our supervision and control.” When we get married, the mullahs must pray so that the marriage can be consummated. It means that sex between husband and wife is not allowed without their permission. When we die, the mullahs shake our dead body in the grave and recite their last prayers. The mullahs used to say that we should follow their orders to go to heaven after death but they have turned our life into hell in this world. From entry to exit, the life of Iranians is under the control of this religious authority. The people of Iran today are rebelling against such a religious authority because Iranians have experienced the interference of religion in politics and personal life to be a disaster.

As a teenager, you fought against the Shah’s regime and were part of a historic revolution. How do you think this movement is different from the uprising of 1979?

A lot of differences can be seen. Firstly, in the revolution of 1979, people revolted against the tyranny of the king. But they had freedom in their lifestyle. After the revolution of 1979, it became a religious dictatorship. And people lost their personal freedoms.

Secondly, the desire for justice and freedom have always been expressed with religious slogans. But now the slogans are anti-religious and people think that their most important problem today is the religious government. Thirdly, in the 1979 revolution, women were not the fulcrum of the revolution. Today, women and their demands are at the center of the revolt. Finally, the result of the 1979 revolution was backward insofar as it sought to return to the values of the past. But the current movement is even more than a revolution, it is a renaissance, pushing Iran from its medieval era to modern times.

In one of your interviews, you had said, “There is a little Shah in all of us.” Would you say that is what encouraged the regime to become so brutal?

The ideas of the revolutionary generation of 1979 were not pluralistic. Everyone thought that the king was ‘bad’ and wanted to replace him with a ‘good’ king. And everyone thought they would make a better king.

In 1979, though people and political groups chanted for freedom, they had in mind another type of dictatorship. The communists of Iran were looking for the dictatorship of the proletariat. Religious people sought an Islamic government. It didn’t matter whether the Left won or the Right. Whoever won would set up a kind of dictatorship, not a democracy.

Today’s generation has the dual experience of a non-religious dictatorship before the revolution and a religious dictatorship after that. That is why this generation is looking for a democracy.

Today’s youth are different from the people of 1979. Our generation did not have access to information. The internet and social media have introduced people to democracy, secularism, human rights, and various lifestyles. During the era of the Shah, severe censorship was prevalent. Even reading political books was punishable. But, as the king was afraid of the people becoming communists, many religious books were allowed to be published and that pushed the society toward fundamentalism.

The generation that is on the streets today is looking for freedom in their personal lives. Traditional marriage has become worthless for today’s youth. Girls and boys choose their life partners according to their own taste. The young generation of today’s Iran is not looking for an ideology that will inadvertently lead to dictatorship and totalitarianism. This generation seeks to experience its own individuality. Therefore, no one can claim to be their leader. The era of ideology and unanimity is over.

In Kandahar (2001), you unravel the role of the US in Afghanistan. From the Arab Spring to Iran’s protests, how do you read the role of the US?

In 2009, the Green Movement happened in Iran. At the time, I spoke with former US president Barack Obama’s team. I told them that the demand of millions of Iranian people was that the US, as a democratic country, should not recognise Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who was alleged to have come to power as the president by fraud. Obama’s answer was: “You are responsible for your democracy, not us. I am looking for a deal with the Iranian government to curb the atomic bomb.” Finally, a few months ago, Obama officially admitted to regretting not having supported the Green Movement.

The reality is that Western democracy is fragile. The role of the West has always been negative for democracy in our region. When Iran was trying to become a democracy in 1953, the West staged a coup against Mohammad Mossadegh (a pro-democracy leader of Iran at the time) and put the Shah in power for the control of oil. During the Cold War, due to their fear of Soviet domination in Iran, the US, through the Shah, provided for the setting up of thousands of religious centers and let the mullahs brainwash the people so they do not become communists. If they (the West) were indeed looking for democracy in Iran, they would have asked the Shah to allow for political parties to operate freely. The West, therefore, is not a supporter of our democracy.

When I watched Gabbeh for first time, the metaphorical call of the horse got etched into my mind. The film calls for the liberation of women’s will. When you see the protests now, do you see the hijab issue at its core?

The women’s revolution started with the demand for freedom from the hijab but it went beyond that and turned into a revolution against all kinds of discrimination—economic, cultural and social. Then there is also religion-based discrimination. If the Sunni government (Taliban) in Afghanistan perpetrates violence on Shias, in Iran, the Shia government marginalises and even punishes religious minorities such as the Sunnis, Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians. For example, the Bahai youths do not have the right to go to university.

What will these protests lead to? Are we awaiting another revolution where, like in your movie, The President, the dictator will be overthrown and roam the streets of Tehran with his granddaughter, learning how to paint, perhaps?

Currently, the only thing that remains of the tyrannical religious government is its facade. Iranian renaissance has already happened in the country’s culture. Most Iranian families are against the religious government and half of the society is not even religious anymore. The relationship between men and women is no longer based on the official religious form. So, I am very optimistic about the future of Iran.

(This appeared in the print as A Women-led Renaissance")