In Britain, the most common point of conversation is the weather. Whether it will rain or it will be a cloudy day or a bright one. But climate change doesn’t enter conversations with the same ease at all. Ask a common man anywhere in the world, “What do you think about climate change?” and most responses will not even include the words climate change. However, pollution, extreme heat, floods, and storms will find a mention immediately. John Marshall, who is trying to improve the communication on climate change conversations, says that the concept has become so abstract that ordinary people feel alienated from it. The crisis is not of how to communicate an abstract idea for a TED talk like Marshall does. In the real world, it boils down to the use of language. Climate change and environmental degradation not only impact our life but also our language, but is anyone listening or willing to change the language of the most dangerous crisis the world is facing?

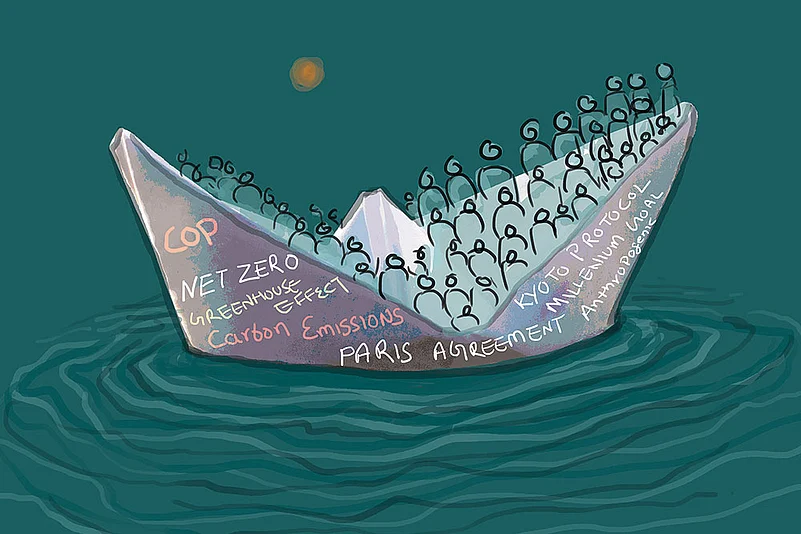

Let me explain with an example. Anyone who is reading this article knows how to read English but how many would be able to explain terms such as COP, carbon emissions, Greenhouse Effect, Net Zero, or anthropogenic? All these words are related to climate change, but they don’t make sense even for someone well-versed in English. Now think about the masses in India of which only a minuscule percent speaks or understands English. This is just one part of the problem. I am yet to underline the concepts and words that originate due to climate change or what scientists have named the age of the Anthropocene. The website of the Bureau of Linguistic Reality has dedicated itself to coining new words for problems arising from climate change. The new words can be from any language, and anyone can propose new words. Let’s take one of my favourites: Nonna Paura meaning “The simultaneous sensation of a strong natural urge for your children to have children mixed with an equally simultaneous urge to protect these yet unborn grandchildren from a future filled with suffering.” Both the words come from Italian in which Nonna means grandma and paura means fear. While looking for words that are not yet in circulation, I tried to find one word for fear of death from pollution. I could not find any such word in the dictionary. I tried ChatGPT and it gave me ‘pollutophobia’, which is nothing but a rendering of pollution and phobia. The world we are living in is threatened by the rapidly changing environment and soon there will be situations for which we do not have expressions or simple terminology that can make people understand the seriousness of the problem.

One interesting thing about environmental disaster or climate change is that it doesn’t discriminate. Remember the Mumbai floods (2005) or the Chennai floods (2015)? Everyone living in the cities was impacted. Rich, poor, middle class, educated, uneducated, millionaire or pauper, all suffered from the devastation. But did that translate into any new linguistic reality in our culture? Writer Amitav Ghosh points out that despite the huge film industries in Mumbai and Chennai, the environment or even these floods never became a subject for the creators. Then, how will a language be developed to convince people living in a small town, village or city that we need to lower our carbon emissions because the earth is getting warmer daily? How will people understand carbon credits, millennium goals, the Kyoto protocol or the Paris agreement? It is not only about the climate but also about the dominance of academic language in policy matters, which we think people living in villages or slums will not be able to understand. The problem is that efforts are not being made to make them understand.

The world Is threatened by the rapidly changing environment and soon there will be situations for which we do not have expressions.

A few years ago, I was attending a course named ‘Fictions of Anthropocene’ and realised that despite the efforts of the professor, most of the reading material came from western writers. This is the irony of climate change where polluters are western countries and the victim is the southern hemisphere, but the discourse is controlled by a western language in its own terminology. I decided to look for material in different languages of India and found amazing writers who explored how climate change relates to people living near rivers, the genesis of the word Anthropocene, poets who have been writing about changing weather, nature and climate change in Nepali, Bangla, Kudukh, Rajasthani and Gadhwali. Most of the languages have tools and idioms to express themselves and also to create new words and expressions if needed. It is not limited to simple words but also applies to serious academic theories.

As a student of literature, I recently got to know about eco-criticism, a fancy term to critique a literary work in terms of ecology or the environment. In the early 90s, this term was coined but something like this had already existed in Tamil literature. The term is called Tinai. According to the theory of Tinai, any literature could be critiqued on the basis of Tinai, which is the organic linkage of time, space, landscape and emotion, or to put it in a more simplistic way—the five elements we are made of—air, water, ether, fire, earth and their linkages.

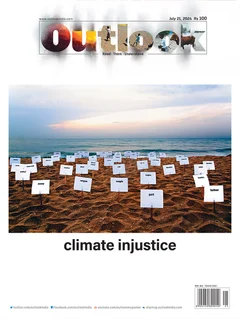

In a multilingual country or in the world at large, the domination of a few languages creates a problem: knowledge becomes the tool to rule. Climate change is one opportunity to change that because the idea of climate justice is deeply interlinked with language. To explain to victims of floods in a village that it was not their fault, and that it happened because of the greed of capital-oriented industrialists. To convince industrialists carrying the flag of development to stop and think about working with nature, it requires recalibration of language. It is a tricky situation and the complicated language of climate change negotiations and its sarkari translations are not going to be helpful. One needs to hear both the problems and the solutions in the language of the victim. The English (or any other dominant language) speaking elites of Paris and Kyoto and London and Luxembourg need to step out of their ivory towers to listen to the subaltern—the victims of floods, storms, earthquakes and pollution in the global south and then need to reinvent their language.

Gayatri Spivak in her famous essay, ‘Can the Subaltern Speak’, theorises that on the one hand, subalterns do not have the language of the elite, so it is difficult for them to speak and explain and on the other hand, she argues that if a subaltern is able to speak to the elite in their language, than he/she doesn’t remain subaltern. Either way, the subaltern cannot speak, hence the question “Can the Subaltern Speak?” For me, this essay initially felt urgent but after several readings, the elitism in the argument becomes evident. As a subaltern, I slowly gained the idioms, language and phrases of the elite but does that make me less subaltern? If an elite commentator can argue his/her hyphenated identity (it has been argued in a diasporic sense by Homi Bhabha), then why can’t a subaltern have that? Why is that when a subaltern speaks in the academic language, he/she no longer remains subaltern. It should be the other way round and a counter-question: the subaltern can speak but is anybody (academics, elites, the intellectual world) ready to listen?

This is the problem in the climate change debates as well. The victims of disasters like floods, storms and earthquakes are used as witnesses, not as people who could be engaged and involved in the policymaking process because that is the arena of sophisticated language where more things are concealed than revealed. It is time to change that language if we want to survive in this Brave New World burdened with polluted air, poisoned water, recurring floods, extreme temperatures, and unseasonable rains.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Jey Sushil is the editor of a book in Hindi on the Anthropocene that includes poems, reportage, dairy, and essays from different Indian languages