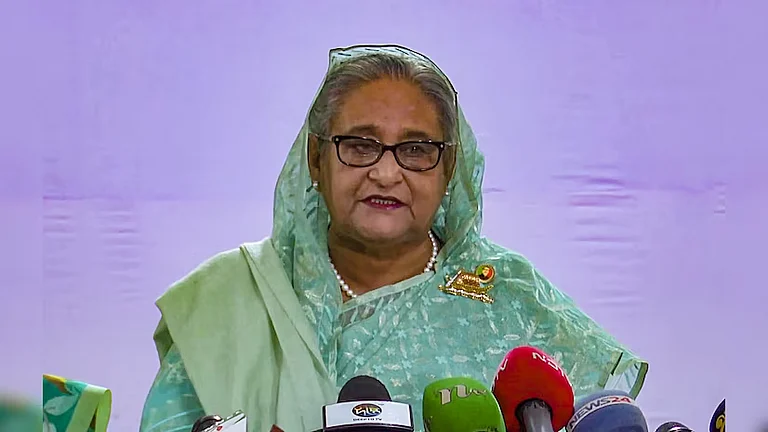

In a national broadcast on August 5, 2024, Bangladesh Army Chief General Waker-Uz-Zaman, dressed in combat fatigues, announced that Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina had resigned, and that the military would establish an interim government. “The country has suffered a lot, the economy has been hit and many people have been killed—it is time to stop the violence.” Zaman also announced his plans to consult the president to form a caretaker government. Within three days, on the August 8, Muhammad Yunus took oath as the chief adviser of the country’s interim government.

The protests in Bangladesh, which started last month over civil service job quotas, very rapidly escalated into an intensely politicised movement demanding Prime Minister Hasina’s resignation. The violence resulted in over 400 deaths since July. Like all previous political turmoil in Bangladesh—or erstwhile East Pakistan—the minority Hindu population, now fallen to about eight per cent, were at the receiving end of the violence. Besides the tragic loss of lives, perhaps the most shocking image that appeared was protesters climbing the statue of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the central figure of Bangladesh’s liberation, using hammers to break the statue. Incidentally, Rahman was assassinated by a group of disgruntled Bangladesh Army officials on August 15, 1975, along with most of his family members, except two daughters, one of them being the ousted Prime Minister Hasina.

In the run up to the liberation of Bangladesh in 1971, nearly three million people were killed in the military crackdown—code named Operation Searchlight—directed by Pakistan’s President Yahya Khan to crush the Bengali nationalist movement. The Pakistan government’s strategy to counter the civil war was to target the secessionists—Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League and the Hindus. The policy was ‘Islamisation’ of the masses, to “eliminate secessionist tendencies and provide a strong religious bond with the West Pakistan; and, when the Hindus had been eliminated by death and flight, their property would be used as a golden carrot to win over the under privileged Muslim middle class”.

According to The Sunday Guardian, the casualty figures of Hindus were between 1.2 million and 2.4 million. As Sarmila Bose highlights in her ‘Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan in 1971’, the minority Hindus were perceived by many in the government, the armed forces as well as the majority population as pro-India and a traitorous force within the country. They were in a particularly vulnerable position during the civil war.

In the ethnic cleansing of East Pakistan in 1971, over 1.5 million homes were destroyed, 30 million were internally displaced and 10 million fled to India. The influx of refugees to India was so massive that by June 1971, the 509 refugee camps set up along the border were finding it impossible to cope with the scale of migration. Eventually, large-size camps, run centrally by ex-Army personnel, had to be established in eight states across India. In August 1971, Pakistan issued a district-wise list of refugees, which included only about one-fourth of the actual number of people who fled from East Pakistan because of the genocide. According to most analysts, the list just about covered the Muslim refugees, implying that the Hindu refugees would not be allowed to go back.

In the larger canvas of geopolitics, it was ‘great power games’ at play. By 1969, Pakistan was proving itself to be more useful than ever before to the US by providing secret channels for communication with China. The US leadership—Nixon-Kissinger—was of the view that the China-Soviet Union tension could be exploited to benefit the US. Given China’s size and growing importance, the US could leverage its relations with China, to counterbalance Soviet Union’s involvement in the Third World and help in a respectable US exit from Vietnam. The US tilt towards Pakistan had two immediate effects—first, President Richard Nixon ordered a review of the earlier Johnson administration’s embargo on US arms supply to Pakistan; and second, the US gave Presidential directions not to ‘squeeze Yahya Khan’. In the event of a crisis, the US would look the other way even as the deplorable genocide was perpetrated by Pakistan. Meanwhile, facilitated by Pakistan, Henry Kissinger visited China in July 1971. Following this visit, the US made it clear to India that it would not intervene in the event of a conflict between India and Pakistan, even if China did so.

China, on its part, adopted a cautious stance, driven by multiple considerations. First, splitting of Pakistan was not in China’s interests, as a liberated East Pakistan would naturally tilt towards India. Second, China needed to retain its influence on the pro-China political parties. These parties had not performed well in the elections held in December, 1970, and with the Pakistani Army’s onslaught against the Bengalis, the remaining influence would further denude.

While China was not inclined towards favouring Pakistan’s military solution, at the same time, it needed to support Pakistan, as their relations were growing closer after the India-China war of 1962. In 1963, Pakistan had illegally ceded 5,180 sq km of strategic territory in Ladakh’s Shaksgam Valley to China. After the Johnson administration’s embargo on the supply of arms, Pakistan was becoming dependent on China for military and economic aid and was trying to open relations with the Soviet Union.

In early 1969, in the China-Soviet Union military clash along the Ussuri River, China had suffered relatively much heavier losses. On the Vietnam front, China’s involvement in supporting Ho Chi Minh against the US was increasing. Opening two fronts, against two superpowers, weighed heavily on China’s strategic calculations. Under these circumstances, Pakistan’s efforts to bring about a China-USA rapprochement were too significant to be disregarded. Overall, China chose to be indifferent to the genocide and destruction in East Pakistan, calling it an internal problem of Pakistan, and continued to supply arms and ammunition to Pakistan. China was bitterly critical of India’s actions like harbouring the Bangladeshi Government in exile, accusing India of expansionism. The massive influx of refugees was of little concern to China.

The current scenario in Bangladesh too appears to be a great power game. The Bangladeshi protesters demand for quota reforms had already been met, and therefore, the Bangladesh Army’s demand for ousting the Prime Minister, followed by the prompt placement of Yunus with close links to the US as chief adviser, and equally prompt recognition and support for the interim government by the US raises obvious questions. Yunus is actively supported by the UK-based Bangladesh Nationalist Party’s (BNP) acting chairman Tarique Rahman, who was sentenced in 2023 for his role in a plot to assassinate Hasina in 2004. The BNP is banking on reinvigorating its ‘India out’ campaign launched earlier this year to win the elections, which is likely to be held soon.

For India, there are multiple challenges unfolding in this scenario. First, the growing popularity of the ‘India Out’ campaign for electoral gains in India’s neighbourhood—Maldives, Bangladesh and occasionally, Nepal—directly counters India’s ‘neighbourhood first’ policy, and by implication, puts India at a disadvantage vis-à-vis China. This brings into question India’s ability to contribute to the broader security framework in the region. Second, with the Bangladeshi military getting more proactive politically, it could potentially turn out like another Pakistan, trying to curry favours with both the US and China, which have generally preferred to deal with more authoritative regimes in this region. Third, the US appears to be playing hard ball to express its intolerance to India’s strategic autonomy. Fourth, unlike in 1971, the domestic opinion in India doesn’t seem to be in favour of absorbing yet another stream of refugees followed by migration. Fifth and finally, a return to the BNP-Jamaat-e-Islami combine rule in Bangladesh is like a reversal to the pre-1971 East Pakistan days when India’s north-east insurgent groups were actively supported and provided safe havens in Bangladesh. The stakes are high, and we can ill afford yet another adversarial front. India must be actively involved to standby its proven friends and prevent Bangladesh’s return to the East Pakistan days.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Subrata Saha is former Deputy Chief Of Army Staff and Member Of The National Security Advisory Board

(This appeared in the print as 'Liberation 2.0?')

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=768&dpr=1.0)