I remember distinctly the day my identity changed. A regular friendly customer for my amiable fruit seller in Kathmandu until then, I became, almost overnight, an ‘Indian customer’. It was October 2015, and the blockade on the Indo-Nepal border had started in the last week of September.

Notwithstanding the semantics of diplomatic denial, there was not a single Nepali who was in any doubt about who was responsible: the Indian government. The larger neighbour had put the squeeze on a country that was still reeling from the aftermath of the massive earthquake in April that year. Dependent on India for much of its essential supplies, landlocked Nepal felt the crushing weight of its most intimate relationship. One of the two boulders which squeezed the Nepali yam was crushing it.

Within a few weeks, it would be time for Nepal’s largest festival, Dashain (Dusshera in India) when the capital would habitually empty out with thousands returning to their villages to celebrate. That year, with an acute fuel and gas shortage, very few could travel home. The city remained full, the mood rapidly curdling against India. The economic integration of the two countries is so acute that it took days, not weeks, for a palpable economic fallout.

At home, my landlady cut down the large trees on the terrace to get wood as fuel for cooking. Terrified that I would not know how to cook using wood, I used my single gas cylinder very sparingly. With frequent power outages that lasted days, I shivered through that winter huddling with a hot water bottle on my lap. Still, I was incredibly privileged and lucky. Hospitals did not have enough electricity and essential supplies for rebuilding the country after the earthquakes could not be brought into Nepal. Medicines were in short supply, not just preventing treatment, but engendering drug-resistant strains such as for TB. Nearly 1.5 million schoolchildren remained out of school. In November, UNICEF warned of a looming humanitarian crisis.

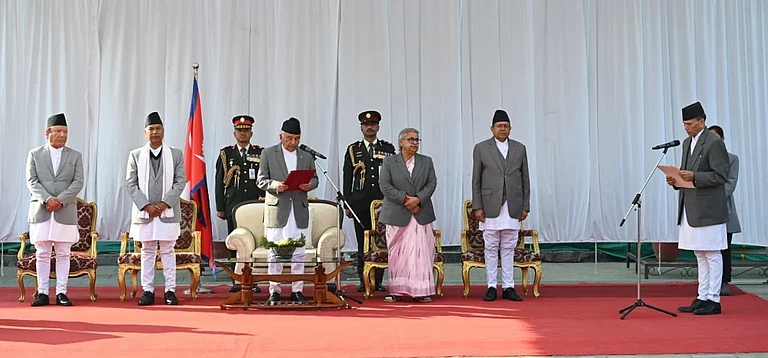

In India, the proponents of the muscular foreign policy exulted, not always silently: India was clearly more powerful and smaller neighbours ought to be reminded of that from time to time. It took six months for the blockade to be lifted. K P Oli, seen in India as the face of anti-India politics, became the Prime Minister for the first time.

Ties That Bind

India and Nepal share a 1,751-km-long border, but much shorter than the border India shares with Bangladesh, China and Pakistan. What makes the border and the relationship with India unique is that it is an open border, and, in theory, allows free passage of citizens.

Nepal is also the country that borders the largest number of Indian states—Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, West Bengal and Sikkim. With a vast part of the border lying in accessible plains and hill areas, where mobility has been easier, there are dense cross-cultural social, familial, linguistic and ethnic ties. While this has brought the two countries together, this has also been a source of uneasiness. The 2015 blockade was a response to the uprising of the Madhesi, the ethnically distinct population living largely in the plains of Nepal, which has, for long, pointed to unequal treatment from the Nepal State. A powerful section of Nepal’s political class, largely from the hills, has accused India of fomenting trouble by harnessing this discontent.

While Nepal’s wide array of political parties—including the three major ones—have always had greater or lesser affinity with the Indian establishment, the blockade of 2015 sharpened the lines of alignment. Nepal turned towards China, expanding and deepening its ties with its northern neighbour, and joining the Belt and Road Initiative two years later.

Even though the blockade is seen by and large as a misstep by India, Indian diplomacy has chosen to feed further on the Indo-China divide, asking Nepal to eschew ties with China for better treatment, and viewing political formations in Nepal almost entirely through this single lens. This single-point approach not only does not help lay a broad foundation for stable relations but is also viewed as Indian intervention in domestic political affairs as India uses its economic might to back selective political forces. This is also self-evident within India as its commentariat chalks up wins and losses for India with every change of political guard in its neighbouring countries.

To lay the entirety of the blame for interference on the Indian establishment would, however, be both inaccurate as well as a disservice to Nepali politicians, many of whom have been adept at leveraging the Indian government’s support. Not only have India’s neighbours become skilled at playing India and China off each other in a bid to harness support from both, but Indian intervention has also been actively sought and welcomed at various points.

In 2005, India mediated a 12-point agreement between the Maoists and the seven-party alliance that paved the way for Jana Andolan II (the People’s Movement of 2006) which forced the monarchy to step down. It also had a role to play in bringing to an end the first term of (Prachanda) Pushpa Kamal Dahal as Prime Minister during a tussle between the first Maoist government and the Nepal Army. In Sri Lanka, India has also played a role in bolstering the political alliance that led to the electoral defeat of President Mahinda Rajapaksa in 2015.

While India’s hand in ending the authoritarian regimes in the neighbourhood has been welcomed, its policy of backing favourites to the exclusion of all other forces has not. By investing in ‘pro-India’ leaders and political parties rather than cultivating a larger pro-Indian sentiment and keeping open the bridges to all political formations, India has narrowed its options and reduced its own strategic maneuverability.

Lost Opportunities

In Nepal, despite the uptick in anti-Indian sentiment, the dense interlinkages and Nepal’s dependency on India provide myriad opportunities for Indian foreign policy to blunt its edge. Shared cultural landscape and historical ties has meant there is enduring goodwill for India and Indians. However, India’s foreign policy has continued on a narrow track—while domestic political considerations have extended into the approach towards Nepal, leading to Nepali intelligentsia protests about Indian Hindu nationalist influence in Nepal.

For a country that India claims is a priority partner, Indian government policy has paid scant attention to Nepali concerns while formulating policies that have an impact on its neighbour—whether it is demonetisation (which resulted in the loss of savings of Nepali migrants working in India) or the introduction of the Agniveer scheme (which has stalled the intake of Nepalis in the Indian army).

Indian benevolence can also come with conditions that feed into the anti-India sentiment. Take the cooperation on the electricity sector, described by the Indian government as a ‘win-win area of cooperation’. In a convoluted agreement, India insisted on a clause that prevents Nepal from using any investment or involvement from China if it wishes to sell electricity to India. Nepal has accepted this, but with some reluctance, seeing it as India’s attempt to use electricity as a strategic rather than a commercial product to reestablish its hegemony. While such agreements may be technically sound in terms of meeting India’s perceived interests in the short-term, in the long run there are political costs to pay for such prescriptive agreements.

While Indian mandarins would argue that India needs to keep its strategic interests in mind, a long-term view of Indian interests should also take into consideration the costs of arm-twisting the smaller neighbour. While a muscular approach is often presented as ‘realpolitik’, devoid of an understanding of existing realities, it is entirely counter-productive as no amount of strategic machinations can stem the rise of anti-India sentiments which in itself undermines Indian interests. Meeting India’s long-term security and stability necessitates a broad-based political approach towards its neighbours that takes into consideration the sentiments on the ground.

(Views expressed are personal)

(It appeared in print as 'Behind the Mountains There are More Mountains')

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Aunohita Mojumdar is an Indian journalist and former editor of Himal Southasian. She is currently based in Bengaluru