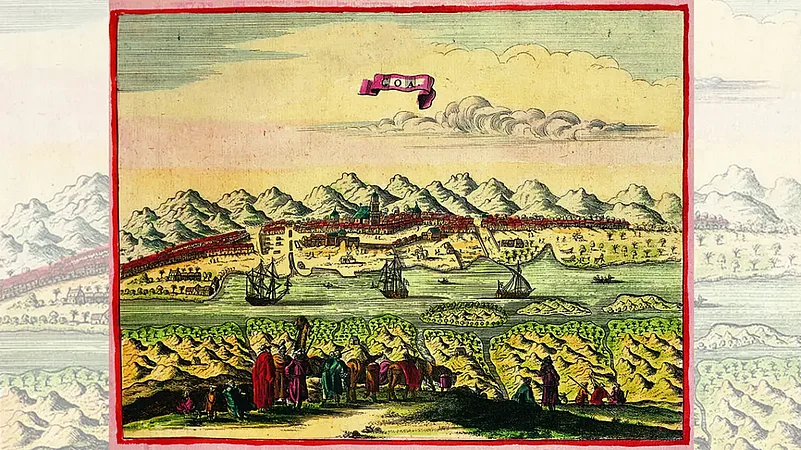

Goa is a special state with a history it doesn’t share with the rest of India. British rule did not extend to Goa, which had uninterrupted Portuguese rule for nearly 450 years since 1510, when the Portuguese established their presence by defeating the ruler of the Bijapur Sultanate. India’s freedom movement against British colonial rule is not part of the state’s collective memory.

Goa became an integral part of India in 1961, after the latter sent its army to ‘liberate’ the former. But 450 years of Portuguese occupation have left an indelible impact on the culture, cuisine and architecture of the tiny state, and gives this tourist paradise a distinct, hard-to-quantify flavour.

ALSO READ: Tears Of The Mermaid: The Melancholy Of Goa

In a delicious irony of history, Portugal’s current Prime Minister Antonio Costa has Goan roots. To the credit of the Portuguese public, their PM’s evident pride in his Goan heritage has not stood in the way of his political ascendancy. The 60-year-old Costa first became PM in 2015 as the leader of the centre-left Partido Socialista. Nobody expected his government to last, but he survived a minority coalition government for four years with far-left support, and won a second term in 2019. Calling snap polls in January 30, 2022, he again trounced his opponents and became PM for a third term, with a clear majority. His handling of the pandemic and rollout of vaccines helped Portugal do better than other European countries.

One wing of his family is still living in Margao, while the PM himself was born in Lisbon. His father, Orlando da Costa, was, in fact, a famous anti-colonial novelist.

Ties between India and Portugal got a fillip during Costa’s three terms as PM. With India gearing up for closer ties with Europe, Portugal’s importance in India’s foreign policy is a given. Delhi and Lisbon have made good use of the PM’s India connection. In 2017, Costa was the chief guest for the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas.

“There is a positive momentum in relations between the two countries. The understanding between PMs Modi and Costa has contributed immeasurably to bringing the two countries closer,” says Manish Chauhan, India’s ambassador to Portugal. “The Porto Summit between India and the EU in May 2021, which was hosted by Portugal, was a landmark event. It brought PM Modi and the leaders of EU+27 together in an unprecedented and historic event, paving the way for more tangible exchanges between India and Europe. Our bilateral relationship has continued to deepen even in the midst of the pandemic, and the two sides have made much progress on issues such as migration and mobility,” Chauhan adds. He says the two countries can cooperate and pool resources on “trade, connectivity, technology, renewable energy, tourism, start-ups, digital connectivity and medical supply chains”.

But relations between India and Portugal weren’t always so good, especially just after India’s independence, when Lisbon refused to give up its claims on Goa. India established diplomatic relations with Portugal in 1949, two years after it won freedom from the British. But soon, relations turned sour over Portugal’s continued “occupation” of Goa. India’s PM Jawaharlal Nehru ordered negotiations with Portugal to give up Goa. But when it was caught in a deadlock, India and Portugal decided to cut off diplomatic ties in September 1955. In 1961, India sent in its Army to liberate Goa. Since then, Goa has been part of India, which put its ties with Portugal in deep freeze. All through this period, changes were taking place in Portugal, with a movement demanding democracy at home and decolonisation abroad. As it gathered force, Portugal’s relations with India picked up, culminating in a 1974 treaty that led to re-establishment of diplomatic ties between the two countries.

The ‘special relations’ enjoyed by Goans persisted even after the state became a part of India. People born in Goa before 1961 were regarded as de facto citizens of Portugal through the Nationality Law 37/81 and additional legislations for all of Lisbon’s former colonies. Portuguese citizenship could also be claimed up to the third generation of descendants of residents in the former colonies. Many Goans used this provision to migrate to Portugal, and from there—with EU citizenship—across Europe. Many went to Britain, which was then part of the EU.

According to a MEA report on Portugal, of the 10 million people in the country, the Indian community is estimated at around 70,000, including over 7,000 who are Indian citizens. This is the third-highest number of persons of Indian origin in Europe after the UK and the Netherlands. The Indian community enjoys a special position in Portugal because of its historical relations with India.

Migration of the community took place in two tranches—before Goa’s liberation, and after. There are others, many of them Gujaratis, who also migrated to Portugal from its former African colonies like Mozambique and Angola.

Marsha De’Souza, 34, is a Goan working at an MNC in Qatar. She has registered for a Portuguese passport as a third-generation descendent of Portuguese colonials. Her reason for doing so is simple. “The opportunities are much better if you have an EU passport. Even in Qatar, Westerners are better paid than Indians. It opens the doors for better jobs. In Goa today, jobs are scarce and not as well paying. Not that I want to leave Goa, but when I think of working abroad, it is much easier with a Portuguese and EU passport.” She has just begun formalities and hopes to apply next year. “I have mixed feelings,” she admits. “If I apply and change my mind, it will be difficult for the next generation.”

Though she was born long after the Portuguese had left Goa, she admits she has great affection for the Portuguese. “They have been incredibly generous to the people of Goa and have welcomed us with warmth. Goans have long embraced Portuguese culture rather than the culture of India.” Was this mostly among Christians? “No, Hindu and Christian Goans share a composite culture, which is different from the rest of India,” she explains.

Joe Broker is a second-generation descendent who opted for a Portuguese passport and used the EU protocol to settle in the UK. Growing up in Indian Goa, his Portuguese speaking and writing skills were not great, precluding job opportunities in Portugal. “If one makes the effort to get into the system, Portugal is welcoming to descendants of its former colonies,” Broker says.

Any regrets on leaving Goa? “Yes, nostalgia. But the Portuguese passport opens doors of opportunity,” he adds. No, there is no regret. In fact, he believes this was the best decision he had made in his life. For the next generation of Portuguese of Goan origin, their old homeland will be a memory.

This is one part of the Goa story. For most of the current generation of Goans, Portuguese rule has no resonance, barring stories retold by elderly relatives.

(This appeared in the print edition as "A Lusophone Route")