On TV they don’t mention it —

the situation inside the earth,

nor the situation beyond the conversation.

There will be no commentaries —

Absolutely none.

from ‘On TV the news showed. . .’

By Anastasia Afanasieva, Ukrainian poet

I have often thought about Andriej and the bulletproof vest. Last Wednesday evening, I asked my friend Marek Kubicki who lives in Poland about the 31-year-old man to whom he had given his bulletproof vest. Andriej was going to fight in the war alongside the Ukrainians in March. He was then living in Poland.

Kubicki said Andriej is alive and in rehabilitation after he was ambushed and taken hostage and later released in exchange for some Russian soldiers.

“Where is the vest?”

“Demolished. He was hit in that vest. It saved his life,” Kubicki wrote back on Messenger.

ALSO READ: 'What Have You Got There, Brother'

“Today Andriej team got ambushed. Two people killed, one lost his legs and Andriej got hit. Bullet proof vest is destroyed but he survived. Epic end of my vest,” Marek wrote to me on March 22, 2022. I was relieved. Over the months, we saw the war unfold. Television channels showed the smoke and the blood and, then, we moved on to other news. But the war continued in Ukraine. The war as news is only good in the beginning when destruction is new, when the sight of dead bodies is not yet routinised, when displacement makes for good visuals. It was the poets and the writers who continued to document the loss, the identity question, the resilience, the hurt and the sadness. They became the spokespersons for their people. They even fought on the frontline.

They continued to resist, with their accounts of everyday life, the claim by Russian President, Vladimir Putin, that Ukraine’s statehood is a fiction. That’s when the ‘invasion’ began. In February.

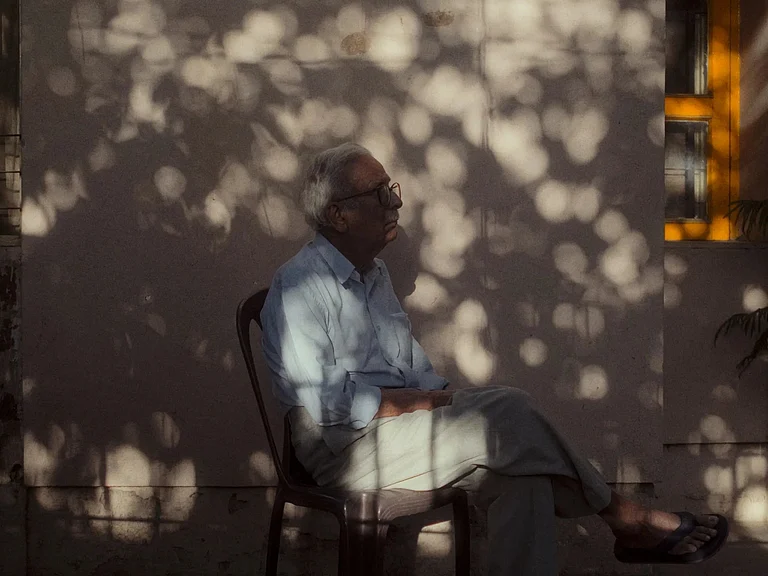

I asked Boris Dralyuk some questions. He was kind enough to answer. That’s how we make sense of war. By reaching out, by talking, by reading, by asking questions, extending a hand from a faraway place hoping someone might hold it and smile, amidst the ruins. This issue is a tribute to the people who sleep everyday knowing that a bullet could end all their dreams. On TV, they won’t mention it. But we have words and paper. We will mention the war, the loss, the love.

Lina Kostenko, translated by Boris Dralyuk with Roman Koropeckyj

The river’s gone, the name remains.

The willows and the moats are dry,

as is the bog. Above the plains,

a wild duck mournfully flies by.

Only the steppe and heat — that heat —

only rare glints of dried-out lakes,

a tired stork trailing his feet,

and, high up on a pole, his nest…

Where are you, rivulet? Arise!

Your banks cry out through their chapped lips.

Your springtimes miss their colored bows.

Heat blazes on your bridge’s ribs.

Over dead rivers, bridges stand.

Storks circle, do their daily chores.

Reeds with black candles in their hands

solemnly walk the former shores...

As a poet and a translator, how do you translate war?

It seems to me that my calling as a poet and translator isn’t to translate war but to translate poems that speak to me directly and powerfully of any sort of human experience, including the experience of war. I’ve translated my share of poems born of and during wartime, but only those that resonate with me, those that captivate me and reveal new insights. I don’t rush to translate a poem, however important and timely, simply because its important and timely; if the poem doesn’t speak to me, I will fail it in English, and there are many other gifted poet-translators who could and should do it justice. If the poem grabs me in the original language, then I know it’s worth my effort to try and grab the reader in English.

What does war mean in a place you left when you were very young mean to you?

I last revisited Odesa in 2019. What I saw was at once new and completely familiar. I didn’t need a map to find the places that I had loved as a child, and the language I spoke was very much the language of those around me. I was home. Perhaps I had better offer a translated poem in place of my own recollections – it says everything there is to say. I shared the poem on Twitter just days after Russia launched its full-scale invasion, saying: “Now I hear the name of my town in reports of shelling and advancing troops. I want people to see it as I do.” This is the poem, by Semyon Olender (1907-1969), another Odesan who lived much of his adult life in Moscow:

Once, on a train, without warning,

I heard two strangers say

the name of the town I was born in

one July, on a warm, rainy day.

And I felt these fleeting neighbors

give off a southern breeze.

I saw the sun of my youth

smiling above the trees.

I remembered it all — the blue sea,

the distant silvery dock,

my friend’s fishing boat, which he

sailed in the morning fog…

The light of the lighthouse, the ships —

how still their shadows lie —

and you, awash in white foam,

home of a childhood gone by.

We may leave our homes, but our homes never leave us, and when they’re under attack, we shake with every explosion.

How do you search for poems that bear witness to what’s happening in a place you don’t live in anymore?

I’ve been translating work by Ukrainian authors like Andrey Kurkov for years, and I am hopelessly addicted to old, half-forgotten books — an addiction shared and fostered by my colleague, Roman Koropeckyj, who taught me so much of what I know about Slavic literatures at UCLA. My colleagues and friends send me new poems and pieces of prose every week. I’m lucky to be embedded in this lively, restless network of writers, translators, and readers.

You have said the city you live in and the city you come from are similar? How so?

In one of my own poems, inspired by the work of the great Odesan-born modernist Isaac Babel, whose marvellously innovative stories of Jewish life and the criminal underworld I’ve translated, I address the author’s uncle, who may have emigrated from the Russian Empire in the early twentieth century and died in Los Angeles: “You find what you were after, Uncle Lev? / You ditched Odesa for a new Odessa.” I say Uncle Lev is “forever stuck between two sweetly rotten towns” — and what I mean by this is that both Odesa and Los Angeles are somewhat charmingly decrepit, yet always active, always on the go. They’re both major seaports, sitting at the very edges of their nations, far from the centers of power and, hence, rather ungovernable. I always feel at home in places like that — places where one feels almost dangerously free.

Why do Ukrainian voices matter in the West?

There is a simple answer: because they are fabulously varied, endlessly interesting, often very funny, often heartbreakingly beautiful. They have earned the right to speak and be heard simply by virtue of their excellence, and for too long they have been violently suppressed by their imperialist neighbor to the east.

How can a poet fight? Can a poet have a role in a war?

Many poets in Ukraine are quite literally fighting on the frontlines, weapons in hand, but poets can also fight through poetry. Their work can remind readers that war is more than a matter of shifting borders and casualty numbers. Every person involved is just that, a person — a person with unique character and a full life. A poem can be, among other things, the crystallisation of a personality. And we need to remain aware that all the people we see fighting and dying, being bombed and tortured, carry within themselves all that makes us human. Poems awaken us to that fact.

Why did you decide to translate the work of Ukrainian lyric poet Lina Kostenko?

I have to go back to my first response: each of the poems grabbed me and wouldn’t let go. I also feel it’s important to share, in a time of war, poems from other periods, which might give readers a deeper and broader sense of Ukrainian life—which might show them that Ukrainian has a long past and a bright future.

(This appeared in the print edition as "“Poetry awakens us to all that makes us human”")